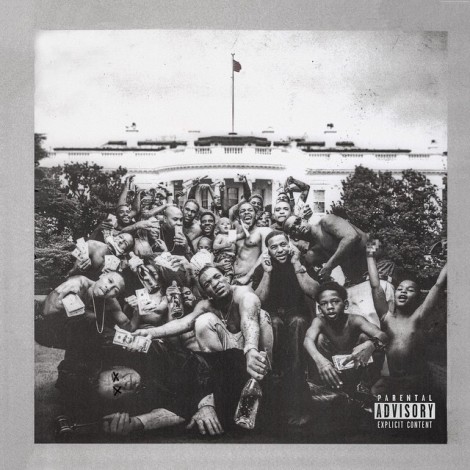

Kendrick Lamar : To Pimp a Butterfly

A butterfly is still a caterpillar. Charles Manson was a psychopathic killer, and Mother Teresa was the emblem of humanitarianism, but, when you break it down, they’re both just human beings. Kendrick Lamar is a mortal man. He says that maybe he’s “just another nigga,” but he’s also grappling with the idea of immortality. With three great-to-incredible albums — Section.80, good kid, m.A.A.d city, and To Pimp a Butterfly — he has climbed the ranks of hip-hop acclaim, but he’s still a kid who grew up in the civic corruption of Compton. And Lamar fully understands this “you’re no better than where you come from” outlook on life. The parallels between Lamar’s own background and that of one of his biggest influences, Tupac Shakur, have placed him as an heir to that throne, and that’s a fair assumption given that Lamar so perfectly splices himself into a past Mats Nileskar interview with Tupac for the final six minutes of To Pimp a Butterfly, a striking 73-minute slab of dark, funkadelic hip-hop. We’re not Lamar, we don’t really know what he wants. He doesn’t say that he wants to be Tupac, but he also doesn’t shy away from the influence of the 19-years-dead Oakland rapper that has sold 75 million records, worldwide.

Lamar has sold around two million records since 2011. That’s an average of about 500,000 records per year, with m.A.A.d city having sold more than one million copies. Since Tupac released 2Pacalypse Now in 1991, he’s sold about 3.1 million records per year. If we’re going to start comparing Kendrick Lamar to Tupac, then there’s still some catching up to do, commercially speaking. But what Lamar does, more than anything, is bring Tupac’s artistic fire back to light. And that’s out of pure fucking respect. “I’m not saying I’m gonna change the world, but I guarantee that I will spark the brain that will change the world,” is the operative Tupac quote here. Back in 2011, Lamar had a vision of Tupac in his dreams, and he said that it inspired him to carry the flame. “It’s a crazy true story,” Lamar told HipHopDX. “A silhouette [came] and he said, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing, don’t let my music die.’ That shit scared the shit out of me! Prior to that, my mom brought up, ‘You know, you and Tupac, ya’ll like days apart, ya’ll birthdays.’ I never knew that shit; that’s some wild shit.” Lamar was born on June 17, 1987, and Tupac on June 16, 1971. While good kid, m.A.A.d city was in production during 2012, Tupac’s hologram made an appearance at Coachella alongside Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, and everyone lost their bananas. Remember, Dr. Dre is Lamar’s executive producer, and now Snoop Dogg shows up on To Pimp a Butterfly’s “Institutionalized,” and it’s one of Snoop’s best turns in years. Connections, people.

Despite the presence that hangs heavy over the record, To Pimp a Butterfly isn’t a reclamation of Tupac-era sounds. The 1970s are apparently back in fashion again, and Lamar taps into that aesthetic with all the funk, soul, and horns that make up the sonic tapestry on To Pimp a Butterfly. There are horn sections and a jazzy sway in almost all 16 tracks; Lamar owes a fair amount of instrumental credit here to bass wizard Thundercat, who plays on at least five tracks, including “Wesley’s Theory,” produced by Thundercat’s frequent musical partner Flying Lotus. Butterfly is loose, and things seem a little hazy. The instrumentation is reminiscent of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, albeit with higher production value and more angst about a world that still places a low value on the lives of black men.

The bass crashes out of the gate on “Wesley’s Theory,” going real low, as funkmaster Geroge Clinton arrives slightly strained (“Look both ways before you cross my mind!”). To Pimp a Butterfly wouldn’t even necessarily be a hip-hop album if Lamar weren’t rapping. “The Blacker the Berry” is the lone, rigid beat track, Lamar’s most aggressive moment — as he launches into a ferocious takedown of racial stereotypes, he sounds like he could tear your face off if you dare cross him. The most memorable hook, anchored by a delicate hi-hat, comes during the hopeful “Alright,” and Pharrell Williams is present for suave choral back up. “King Kunta” is the contender for the funkiest groove of the bunch, Lamar referencing Michael Jackson (“Annie, are you okay?”) and a re-imagined Kunta Kinte from Alex Haley’s Roots, as the song squeals out into an acid guitar solo. “Momma” has a pinging noise that sounds like a foosball hitting a cowbell, and “How Much a Dollar Cost” would be right at home in a dimly lit jazz club, Lamar sitting on a stool, scotch in hand, with the band locked in behind him as he wrestles with the consequences of giving a dollar to a homeless man.

To Pimp a Butterfly is complex, both lyrically and musically, but that Tupac interview at the end may say the most of any track. And there’s two moments during the album that lead up to the groundbreaking conversation between one dead and one living rapper: the early 1990s feel of “Hood Politics,” and the mysterious voice in “For Sale?” asking, “What’s wrong, nigga? Isn’t this what you wanted?” This could be taken as Tupac returning to Lamar’s dreams after his fame was fully realized post-m.A.A.d city. “I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence / Sometimes I did the same, abusing my power, full of resentment / Resentment that turned into a deep depression / Found myself screaming in a hotel room / I didn’t want to self destruct,” Lamar repeats in spoken word throughout Butterfly. Is he seeking spiritual guidance from Tupac? Hard to say for sure. Lamar asks Tupac if he thinks of himself as a rich man or someone who made the best of his opportunities? Tupac replies that he’s a natural born hustler — a true hustler. He realized his potential, and made millions by being built to own his own brand. “How did you keep your sanity,” Lamar asks. Tupac says it was God, faith in all good things come to those who stay true. Lamar wants to know if Tupac was a fighter or a reactionist — Tupac met resistance with resistance. “Are we fighting a war we can’t win?” Lamar asks. Tupac’s response is that black men have five years to show their power. Once they turn 30 years old, the world takes their heart and soul. But Tupac was murdered, in his prime, at 25. “You don’t see no loudmouth 30-year-old motherfuckers,” he says. Lamar is concerned about the future of his generation — Tupac says people are tired, murder and bloodshed are coming; nobody is playing around anymore. Lamar’s only hope, then, is the music and the vibes. His energy just comes, and some of that vigor comes from the memories of “dead homies,” like Tupac, who had a story to tell.

Lamar is a caterpillar that morphed into a butterfly. He ate, consumed for protection, and observed the harsh world that often treated people like himself without kindness or compassion. He has the talent, the piece of mind, but faces some harsh realities — getting “pimped” (to use the title phrase) by the record labels, being taken advantage of, and becoming a capitalist prop. The caterpillar’s cocoon is a form of institutionalization. Lamar may have once felt trapped, but he grew wings to set himself free. But as insular and inward-thinking as Lamar’s metamorphosis is here, his music remains wholly universal. At a recent Perfect Pussy show in Massachusetts — they’re a noise punk band, mind — the set started with “Alright” blasting through the PA before getting swallowed by swirling feedback, just like the ground that will swallow the evil, as Tupac says. The poor people are the ground, and they will swallow the rich. These are dark times we’re living in, and there are more ahead of us. But, as long as we have the music, we’re going to be all right.

Similar Albums:

D’Angelo – Black Messiah

D’Angelo – Black Messiah

Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city

Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city

Parliament – Mothership Connection

Parliament – Mothership Connection