The turn of the 1970s had The Rolling Stones on top of the world. If the Stones ever were “The World’s Greatest Rock ‘n Roll Band,” it was during their 1968-1973 run, during which only Led Zeppelin approached or matched their overall stature in the genre.

The Stones recorded Sticky Fingers from 1969-1970, releasing it in ‘71. To paraphrase Frank Sinatra, 1970 was not a very good year, and nor were those that flanked it. Not for much of the world. JFK, Malcolm X, MLK, RFK and Fred Hampton were all dead. By 1970’s end, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin would join that list. Nixon was “de-escalating” the Vietnam War by secretly expanding USAF bombing runs into Cambodia, planting seeds for the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. Sociopolitical upheaval—often accompanied by slaughter, torture and disappearances—was either raging or primed to explode all over the world, from South America and Africa to the Middle East and every corner of Southeast Asia not already mentioned. The U.S., U.K. and various European nations were entering years of lead, deepening the cynicism and anger that vast swaths of the population had been inculcating for years (or much, much longer in the case of marginalized groups everywhere).

Some might argue The Rolling Stones already made the ideal album for this worldwide feeling a year earlier, with Let It Bleed. A song cycle highlighting working-class desperation, protests, serial murder, malaise and unrequited love would seem to fit the bill, to say nothing of the chaos (“Rape! Murder! It’s just a shot away!”) foretold by “Gimme Shelter.” The Stones themselves bore their own scars from the turn of the ’70s and kept re-inflicting some of them: the mysterious drowning death of their multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones, fallout from the deaths at the Altamont Festival, the persistent drug and alcohol habits (and resulting legal issues) of, well, almost everyone in or closely associated with the band.

It’s thus unsurprising Sticky Fingers abandons the strains of hope that echo throughout Bleed for cynicism, bitterness, loneliness and despair. By tapping into these undercurrents (intentionally or not), broadening their exploration of American music to include country and soul, and composing and performing every note with passion and precision, Fingers also takes position as the Stones’ best album.

***

If you’re going into this album cold, Sticky Fingers likely doesn’t sound emblematic of its time and place … for a little while. “Brown Sugar” starts us off with a signature Stones blues-rock rave-up, and 53 years later, from a strict musical perspective, it still goes. The breakdown dominated by Bobby Keys’ saxophone solo is one of the best isolated moments in the band’s discography. Then you realize its lyrics are highlighting slavery, sexual exploitation and heroin. Mick Jagger recently admitted he was going for shock value that wasn’t appropriate in today’s climate; the band removed “Sugar” from its setlist in 2021. Keith Richards, meanwhile, posits the song as a subversive critique of slavery’s horror. Jagger setting those lyrics to such an upbeat arrangement perhaps grants credence to Richards’ argument, but it’s impossible to know for sure. One thing you can conclude with some certainty is that it takes a pretty cynical mindset to think the lyrics funny, even if we could prove the ultimate intent was razor-edged Juvenilian satire.

When I discovered the record at around 17, I definitely understood the most obvious offensive lines, like the entirety of the first verse. (It’d be a few more years before I grasped the cunnilingus and heroin references.) I remember my general reaction being something like, “Why? What’s the point?” I concluded then that it was “one of those things bands used to get away with and it’s good they can’t now” … which, even with my caveat at the end, is a thought I’m not exactly proud of. But as Sticky Fingers became one of my constant rotation albums, I’d find myself skipping the song more often. When going through Fingers for this piece, listening to “Brown Sugar” was a necessity; I understand why plenty of people ignore it. This time, the excitement in Jagger’s vocal performance struck me as almost performative, especially the famous closing “Yeah, yeah, yeah, whoo!” Or perhaps I’m overthinking an offensive song that was expressly written to offend.

This, however, gives me an easy segue into the secret of Sticky Fingers: If you skip its opening track every single time, or delete it from your downloaded or streaming version, the album would still be the Stones’ best.

“Sway” could’ve been a perfect opening track: Despite its slow tempo, it’s one of the band’s standout rockers from a period in their catalog that’s chock full of them, with ferocious solos at the bridge and climax by Mick Taylor. “Sway” is also, as a chronicle of depression and grief, much much more in keeping with the album’s overall mood than “Brown Sugar.” “Did you ever wake up to find/A day that broke up your mind/Destroyed your notion of circular time/It’s just that demon life has got you in its sway.” We’re a long way from “I can’t get no, sa-tis-FAC-tion,” in terms of complexity if not sentiment.

I realize I may be giving the impression that Sticky Fingers is somehow the Stones’ Skeleton Tree. It most certainly isn’t. “Dead Flowers” is a black-comic kiss-off, and the hardest-rocking tracks, “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” and “Bitch,” are as intensely libidinous as “Brown Sugar” without that song’s baggage. But I wouldn’t describe either of these songs as lighthearted. There’s an intense edge to them. And a haunted, uncertain feeling—a sense of a need that may never be fulfilled—lingers over the entire album.

***

Most retrospective reviews of Sticky Fingers—usually written in the wake of deluxe rereleases, like the 2015 package—comment on the Stones being in sync for each song like never before. They’re correct, of course, and part of the reason why was how fucking chaotic their recording sessions had been for the last several albums. (Brian Jones receives the lion’s share of the blame for this due to the intense escalation of his drug use and resulting instability. But suffice it to say he wasn’t the only reason.)

The impact of bringing in Mick Taylor full-time as lead guitarist can’t be overstated. Sticky Fingers is the real coming-out party after he showed a bit of what he could do on Let It Bleed: He’s technically precise and a perfect foil for Keith Richards—their guitar interplay on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” and “Bitch” is thrilling, especially Richards’ foundation for the virtuosic solo in the former’s coda. Throughout the LP, his lead riffs and lines are as much a unifying force for this set of songs as the Jagger/Richards melodies. The Stones also had the most ironclad rhythm section in rock at that time in Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts. The band’s supporting cast—regulars like Bobby Keys, Nick Hopkins, Jack Nitzsche, Ian Stewart and producer Jimmy Miller, plus guests including Jim Price and the legendary Billy Preston—accent the core arrangements perfectly.

While the recording process was fragmented—tunes were mostly cut in the Stones’ famous mobile studio or at Muscle Shoals, and “Sister Morphine” dates back to the Bleed sessions—it must’ve felt practically tranquil compared to the late ’60s run. Accounts of the Shoals sessions portray them as running smoothly. During the mobile studio sessions, Taylor’s presence could stabilize things when Richards would start seeming a bit more like Brian Jones than the workhorse he’d been on Banquet and Bleed.

***

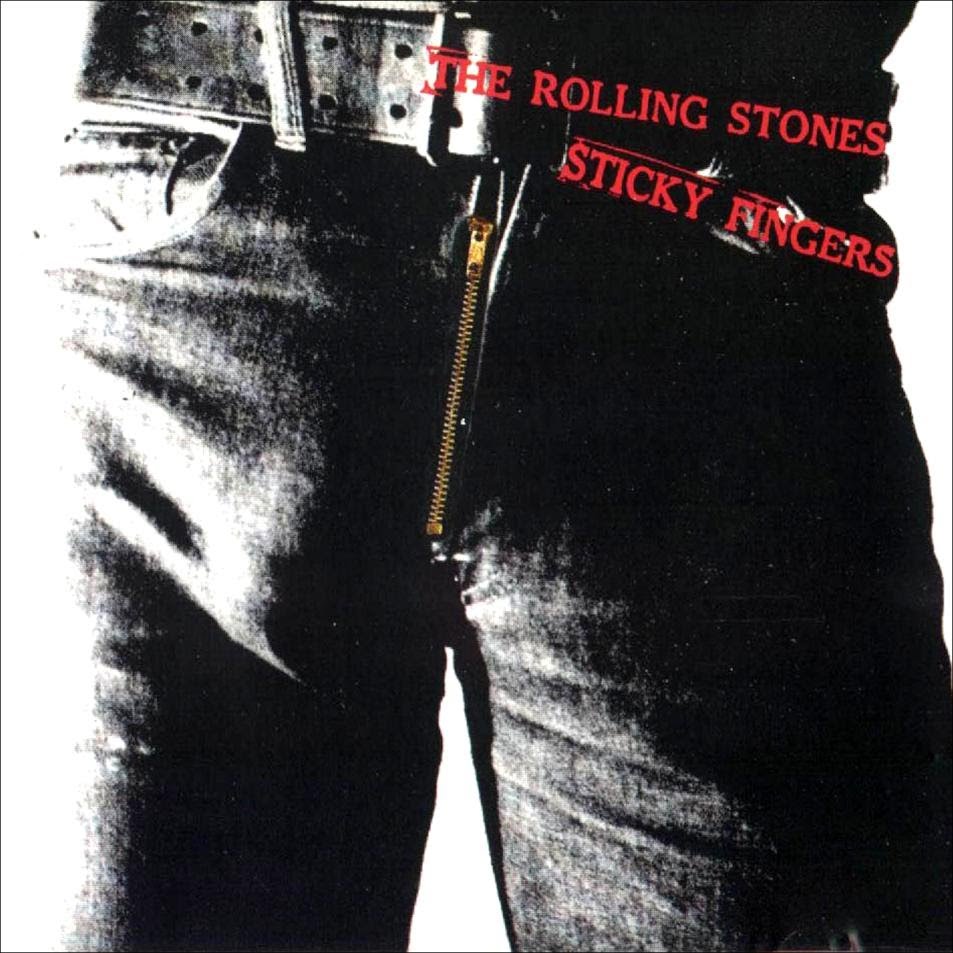

The circumstances were perfect for the Rolling Stones to create a truly exceptional record in this interregnum between two periods of excess and hedonism. That’s exactly what they did on Sticky Fingers. But the accumulated toll of their meteoric rise and everything that came with it meant the album carried a dark weight, one that can’t be undercut by Andy Warhol’s flippant cover art or Jagger’s use of a put-on drawl for “You Gotta Move” and “Dead Flowers.”

Perhaps this is attributable to the album’s wholehearted embrace of country, which we know to be goth AF. It’s not the only genre curveball Sticky Fingers throws, of course—“I Got the Blues” is a sincere soul ballad, featuring one of Jagger’s best vocal performances—but the spirit of country pervades most of the songs. Sometimes it’s country blues, like the rendition of Fred McDowell’s take on the standard “You Gotta Move,” where the aforementioned absurd voice Jagger uses doesn’t diminish how sinister the track is. “White Horses,” meanwhile, dives headlong into country with complete sincerity, and now endures as one of the Rolling Stones’ signature songs. Synchronized acoustic strum dominates the song, but bursts of electric lead lines by Richards feel like outbursts of tears as this song of faded love reaches its emotional climax. Lyrically, “Let’s do some livin’, after we die” seems pretty self-explanatory. You can almost imagine George Jones singing that line, or perhaps “I know I dreamed you/A sin and a lie/I have my freedom/But I don’t have much time.”

Then there is the unrelenting nightmare of “Sister Morphine.” The arrangement is fairly straightforward: Initially, it’s a simple acoustic riff by Richards under a soft vocal from Jagger. More instruments (Wyman’s bass, Ry Cooder’s slide guitar) entering as Jagger’s hospitalized, addicted narrator loses his calm, howling “Why does the doctor have no face?” I’ve never forgotten that lyric and its accompanying image, and don’t think I ever will; to me it’s far more frightening than the song’s bloody, possibly suicidal finale (which the full band joins). The music on “Sister Morphine” doesn’t fit easily in any one genre, but the songwriting—vivid, emotionally brutal images expressed in clear, uncluttered language—is pure country.

I have no idea whether Jagger, Richards and co-writer Marianne Faithfull had any metaphorical intent when writing the song. But I can’t help but see that withdrawal-crazed addict as an emblem of the world of the late 1960s and early ’70s. A populace driven by war, economic difficulties, reactionary politics and other crushing forces to rage, despair or even madness. Pleading for their own versions of Sister Morphine to take away the pain.

After a song like that, you need a comedown, and that’s what the honky tonk black-comedic “Dead Flowers” provides … right? Over a lackadaisical backbeat and clean acoustic lines from Jagger and Richards perfectly matching Taylor’s pedal-steel-mimicking lead, Jagger’s leering protagonist mocks his imperious ex and finds release in another girl. Oh, and also heroin. The drug that’s all over this album. The darkness that cannot be escaped. Closer “Moonlight Mile” sounds almost like a ray of hope with its gorgeous string arrangement by Paul Buckmaster and one of Jagger’s more emotive vocals, but it’s a song explicitly about loneliness and isolation. As great an album as Sticky Fingers is, I sometimes feel glad that it’s over.

***

Of the albums generally considered the Rolling Stones’ artistic peak (Banquet, Bleed, Fingers and Exile on Main St.), the first two were about as acclaimed then as they are now. Exile, famously, had initial mixed reviews before eventually becoming every third rock critic’s favorite album.

Sticky Fingers is somewhere in between: The album was No. 1 on the Billboard 200 and “Brown Sugar” hit No. 1 on the Hot 100 (because of course it did), and the reviews were technically fair to positive, but the extant quotes you find from them seem not to understand the album, and still characterize it as just the latest epistle from a band better known for its hedonism than its music.

The album’s greatness has mostly been realized in retrospect. You’ll now find many who either think it’s the Stones’ best or place it under only Exile and/or Let It Bleed. If you listen to it fresh now, the album’s through-line of darkness and despair will seem so obvious that you won’t understand how it was ever missed.

When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums included are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.