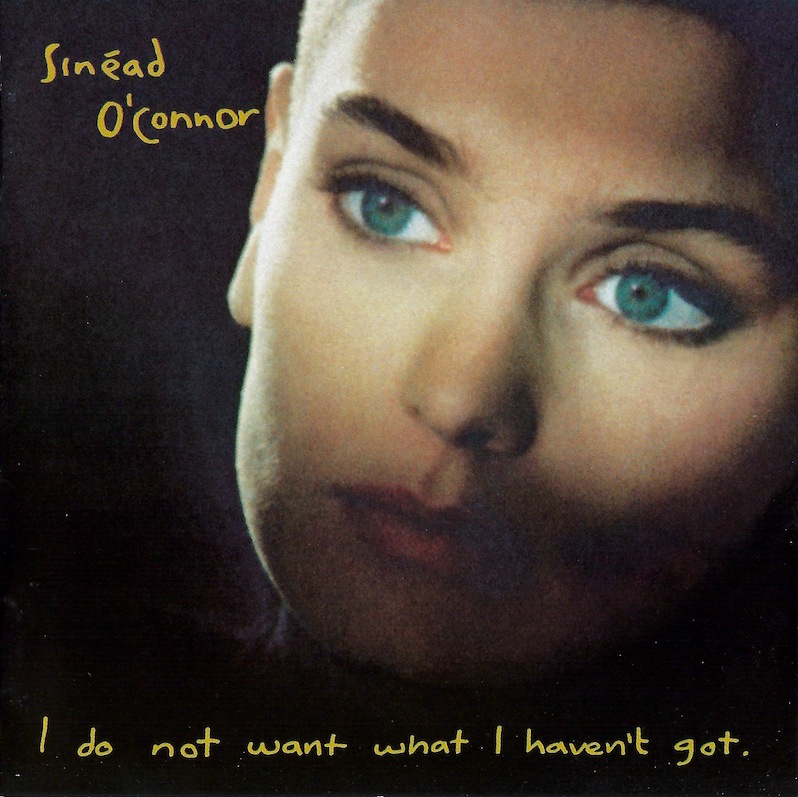

Sinéad O’Connor communicated the truth on I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got

When Sinéad O’Connor released her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, in 1990, I was 15. Although too young to really understand it, the album was unlike anything I had ever heard.

Her death on July 26 at 56 brought back those early first impressions. As a teen, this album felt shocking. It left an indelible mark on how I perceived music. Through her voice, I found music could be much more than about love, hate, and relationships strewn across sets of lyrics, a bridge and a chorus. O’Connor was trying to actually say something. What it was I wasn’t sure, but I knew enough to realize she was misunderstood, that her basic freedoms and rights were under attack. Singing was how she communicated her feelings. Her courage in creating such an honest and personal album taught me that it’s OK to speak up even when you think no one is listening, even when others don’t agree.

After years of listening to a broad cross-section of radio hits—groups like Tears For Fears, Wham!, the Pet Shop Boys, Phil Collins, the Beatles; female pop artists like Janet Jackson, Blondie, and Madonna, and “alternative” music like the Clash—O’Connor intrigued me. I was enthralled by her vocals on “I Want Your (Hands On Me)” and the acrobatic way she skewed and bent her words.

She was nothing like her female contemporaries on MTV who were splashed across Teen Beat magazine. Cyndi Lauper was kitschy and colorful and fun. Madonna courted controversy, yes, but made infectious dance and pop hits channeled through provocative images based on sexual desires. Stevie Nicks seemed surrounded by a mystical shroud, while Joan Jett was just one of the guys.

O’Connor shaved her head and wore plain, drab clothes. When she performed, she gesticulated wildly as if possessed. She was not a material girl at all. I needed to know more.

The opening track of I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, “Feel So Different,” set the tone and established her unique, bold style and unabashedly laid out powerful convictions. When I heard her bare voice set against the swirling strings of an orchestra on the opener, I never felt so alone. O’Connor stretched out words like “so” and “different” until hearing it became nearly uncomfortable. Whatever she was going through, it was massive.

As I listened, I began to understand how these songs were highly provocative for the time as well as steeped in Ireland’s history. “I Am Stretched On Your Grave” is based off a 17th century Irish poem “Táim sínte ar do thuama” from this compilation; in the passage “From the Cold Sod That’s O’er You,” the writer never “severs” from the dirt that lays over their loved one. The mental image of a secret tryst over a grave was jarring. Even more so was using a James Brown sample from “Funky Drummer.” The slowed drum pattern enshrouds the song in a darkness and a depth that threatened to bury whoever was singing. As the rain and wind weathered her body away, she stayed. Unearthly collisions of drums and clanging get louder and more insistent, as her body wears down to the bone. The last measures collide noisily with a riot of strings—chaotic and powerful, it goes on endlessly, then is silent.

Conversely, Sinéad O’Connor also created simplicity and quiet on this album. She strummed chords so that every string was heard, and used precious space to let her words breathe and take new shape. It was chilling. She sounded beautiful and ugly and raw at the same time. She whispered words, and sang them as loud as she could. “You Cause As Much Sorrow,” has a melancholic melody with piano and softly plucked acoustic notes that was only slightly brighter than the tone on “Stretched,” but which still left the protagonist tortured.

In “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance,” O’Connor talks in clinical tones about severing ties in a divorce. The tension spills over and explodes into the chorus that echoes, “I’ll talk but you won’t listen to me / I know your answer already.” It shattered me. Now as a mother, I understand “Three Babies” more fully than I did as a clueless teenager. Saying you’ll lay down your life for your child isn’t an outrageous statement—that’s just your job. But singing about gathering your energy from inside, refusing basic nutrients, it sounded radical at first. The song’s meaning remains unclear. The babies’ “cold bodies” hint at miscarriage. Maybe she’s unable to let them rest. These babies were ripped from her for unknown reasons—because the subject was being violent, or was protesting something, and was maybe called a “bad mother.” Much of the lyrics are sung in first person, so it’s difficult to separate the singer from the unknown person in the song. Her first son, Jake, was still quite young when the album was released, and she later had custody battles of her own. Last year, her son, Shane, 17, ended his life, and O’Connor was devastated.

“Nothing Compares 2 U,” penned by Prince, was a worldwide success, but I was more interested in the tunes with global messages that revealed her social activism. On “Black Boys on Mopeds” she unapologetically took her critique to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. She shattered the image of a proper and good England and replaced it with the reality: that its underlying culture was draped in racism and deceit. She was well aware she would face opposition for stating her beliefs. Her lyrics proved eerily telling: “These are dangerous days / To say what you feel is to dig your own grave.”

On the a cappella title track, she carefully and measured out every whispered word upon a quiet canvas. Walking through an arid hell to reach some enlightenment, she imagines an ocean and a bird. When she discovers the bird is her, it turns worn and faded. But O’Connor is not deterred. “I am not frightened although it’s hot / I have all that I requested / And I do not want what I haven’t got,” O’Connor says plainly.

O’Connor’s death, days before that of Paul Reubens, another misunderstood “outcast” who is being remembered for his unique style of comedy and love for life, is a reminder that the people we should treasure most are sometimes treated the worst.

Sinéad O’Connor bared her soul to us, yet we’ll never really know her pain. Thank you, Sinéad, for the beautiful music you gave us.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.