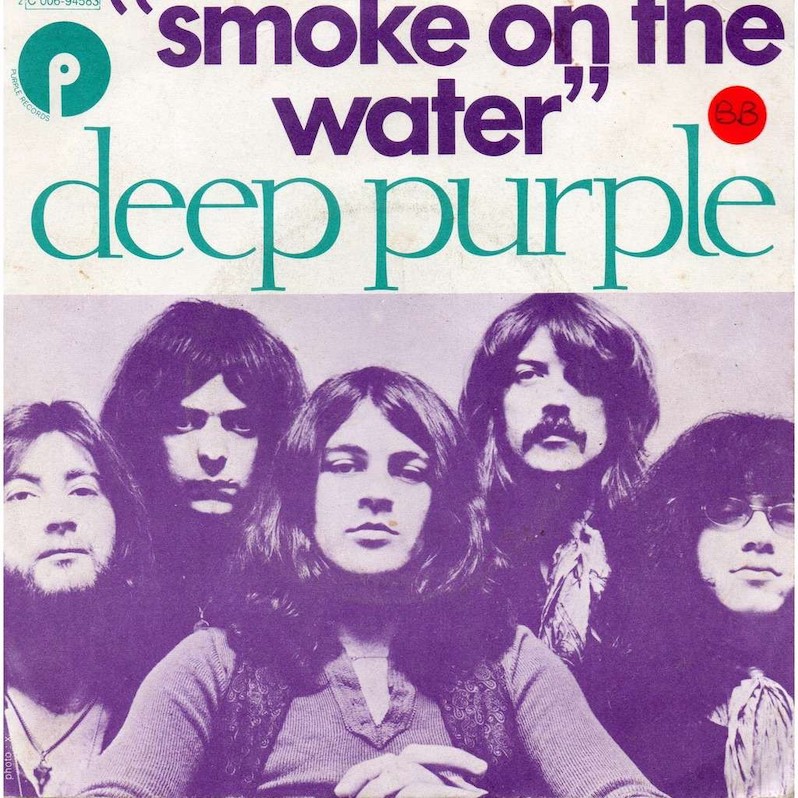

Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water” and a notorious concert fire

Smoke on the Water—it just sounds cool. Rolls off the tongue, evokes a stark image but, in the grand scheme of things, would be no less effective even if it meant absolutely nothing at all. Nobody gets into rock ‘n’ roll for the sake of articulation. Smokestack lightning, jumpin’ jack flash, TNT—if you the only imagery you have in your arsenal is flashy, terrifying and potentially destructive, then you’re on the right track.

It’s perfectly understandable to assume that was the beginning and the end of “Smoke on the Water”—a turn of phrase that conjures up vivid imagery only for the sake of being a badass rock-guy hook. “Smoke on the Water” is the stuff of stoned teenage recklessness and airbrushed custom vans. It’s meant to be heard in quadrophonic sound and it always—always—sounds better when you’re playing air guitar along to Ritchie Blackmore’s signature riff, or kinda-sorta mangling it like Jimmy McGill does on Better Call Saul, or ad-libbing new lyrics about candy bars like Homer Simpson does. It’s not on the soundtrack to Dazed and Confused—that’s “Highway Star”—but it might as well be. It has smoke in the title and it kicks ass. Sold. Next topic.

“Smoke on the Water” is more than mere stoner rock ‘n’ roll fantasy, though, but rather a true story about the harrowing night of December 4, 1971. Deep Purple had begun recording in a mobile studio owned by The Rolling Stones—literally called the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio but incredibly referred to in the song as the “Rolling-truck-Stones-thing” by Ian Gillan in the lyrics—temporarily housed at the Montreux Casino in Switzerland. That same night, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention performed a headlining show at the casino’s theater—which caught fire just as Don Preston began his synthesizer solo during the song “King Kong.”

Now, it’s not necessarily rare for people to be driven to acts of wanton destruction by the power of rock ‘n’ roll—Woodstock ’99 was by no means the first or the worst act of concert pyromania—but the Zappa show fire happened for particularly idiotic reasons: “Some stupid with a flare gun,” as Gillan describes him (and it was almost definitely a him) shot a flare into the rattan ceiling, and well, that’s when all hell nearly literally broke loose: “They burned down the gambling house, it died with an awful sound.”

In his telling of the events in the song, Gillan commits an act of stylized journalism. Even the names haven’t been changed; Frank Zappa and the Mothers and Funky Claude (Claude Nobs, director of the Montreux Jazz Festival) who was “running in and out, pulling kids out the ground,” with the sole exception of that “some stupid.” (Swiss police had a suspect, though, a Czech national who fled the country after the incident.) Remarkably, though, while the fire itself was a nightmare for both concertgoers and the casino itself, nobody perished in the disaster, which means this is a particularly upbeat ending to an entry of Blood on the Tracks.

Hilariously, that’s not the end of the story. No, the casino catching fire, burning down, and everyone miraculously making it out with only a few bruises and a lingering cough isn’t the sole triumph of “Smoke On the Water.” The climactic end to this harrowing tale of rock ‘n’ roll gone wrong is that Deep Purple actually got to finish their recording session! “We ended up at the Grand Hotel/ It was empty, cold and bare,” sings Ian Gillan. “But with the Rolling-truck-Stones-thing just outside, making our music there.” Now that’s how you end a story of peril and redemption—after a fire nearly threatens to claim hundreds of spectators and potentially the observers in the band themselves, they somehow still manage to come out of it with a hit song. Now that’s rock ‘n’ roll.

(Guitar riff.)

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.