Summer of Soul is a celebration of Blackness

America always manages to bury the Black people that serve it the most. It’s just a matter of when. If it’s not the police, it’s the drugs. Not drugs? Probably the sugar. Hypertension isn’t just a disease, it’s the thing most Black people get trying to survive for as long as they can in a hypertense situation that surrounds them that ends six feet under. And only then.

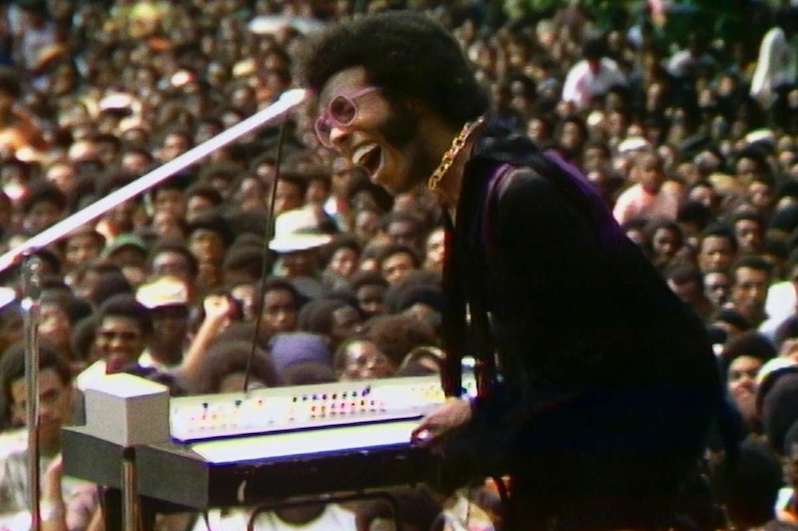

They almost buried the Harlem Cultural Festival, too. And if you’ve seen Summer of Soul—the year’s best documentary that should be up for Best Picture—your instinct after being blown away by two hours of footage from the likes of Stevie Wonder, the Fifth Dimension, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Nina Simone, The Staples Singers, Mahalia Jackson, a surprise appearance from Sly & the Family Stone (things continue like this for quite some time lineup-wise) would be: How can this many wings of the Hall of Fame performing at the peak of their powers in live and living color get buried for 50 years?!

It turns out people didn’t have a problem with the live part. The color of those so ebulliently living on those six weekends in the former Mt. Morris Park now renamed for Marcus Garvey…well, there you have it.

Among everything it is, Soul is a celebration of blackness. From the fits to the music to the politics, 1969 was a year of brilliant defiance that dappled the skies with the fists of the black and brown. While there was reason to be afraid (unpopular war, racist infrastructures, uncaring if not outright murderous police—yikes) there was also reason for joy.

The Harlem Cultural Festival showed off the best ways to get it, too. Whether it was Sly & the Family Stone confusing the majority of the crowd with their partially white rhythm section before indoctrinating them all into their ministry of funk; whether it was Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples alternating and then dueting on Precious Lord (Take My Hand) in honor of the recently assassinated Dr. King that will take every living thing it touches to church; whether it was Ray Barretto hoping and borderline pleading for his people, for some force, for some thing to turn the direction that the tide was turning; whether the fact it was that no single person who made the news from the night of the moon landing at the Festival gave a rat’s sweet ass that whitey was on the moon when Harlem was going through an heroin epidemic and could’ve used some money to help combat it—the fact that the movie is somehow more than all of that is as great a find as the fact that, for two generations, this languished in a New York basement is as great a loss.

The movie is ephemerally fast. It dodges and bobs and weaves like Ali dodging the draft that very year. You get unforgettable performances from the likes of Stevie Wonder interspersed with his personal evolution from the concert going forward to the present day that feel like they could be their own two hour documentaries.

?uestlove makes an emphatic directorial debut here, but years ago when assistants to the festival told him both about it and the long-lost footage, his reaction was outright skepticism until he, too, ended up almost immediately hypnotized by the footage and fought to put it in front of as many eyes as possible. In interviews he’s mentioned that there were some 40 hours of footage he culled the movie from, and that before it was pared down into a blistering two hours, the running time ran closer to three and a half. Ahmir Thompson is well-known as a music nerd’s music nerd, so for him to have missed out on this until recently further speaks to the depths that something this historically significant had been put.

It is very rare that a movie is both great and leaves you wanting more, but Soul is rare because the entire journey to get to this point for this film is rare. More than anything, the film gives and leaves you with a palpable sense of wonder. It is an emphatic throat clearing to kick a film off with a 19-year-old Wonder cribbing some Isley Brothers before launching into a grown man’s drum solo and then somehow improve on that, but it’s also a sly reference not only to what the movie will do to its viewers but how it will turn out bookending itself. And whether it’s the attendees who were happy children or the performers themselves, when they see the footage themselves, you can see the sparkle in their eyes just as much as a reversed image of the good old days.

Summer of Soul has two hours of that feeling that lasts with you after it ends. It is available on Hulu, but if possible catch it in a theater. I was fortunate enough to catch a matinee of it the day after catching it on Hulu, and while the attendance was low once the movie started in earnest something rare in my filmgoing experience happened: no bathroom runs.

From anyone.

The same feeling given back to the subjects of the film was palpable in the theater. It wasn’t too long before people were leaning forward in their seats, or clapping their hands, or whooping loudly whenever another lights out performer(s) went on an epic run. Yet, when the movie turned to the serious side of edutainment, it was the only thing to be heard.

It’s a delicate balancing act, to intertwine joy and pain. And if you’re spending your life trying to avoid being buried, it’s another ball you have to try and juggle with all the rest.

They tried to bury the Harlem Cultural Festival—the entire history of this country is white people trying it. Summer of Soul is a five-star rebuke to those of them that would.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Butch Rosser is a frequent writer, part-time DJ and full-time audiophile. In addition to his Treble contributions, he is currently at work on his first novel, The One Man Jihad. He lives with his fiancee and her cat.