In 1964, one year before releasing Pastel Blues, Nina Simone wrote “Mississippi Goddam,” a scathing protest song about the glacial pace of social and economic change for Black people in America. Employing a buoyant pace to belie its serious lyrical content, Simone called attention to the murders of Emmett Till and Medgar Evers, and the bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama. She called it her “first civil rights song.” “You don’t have to live next to me / just give me my equality,” she sings in one particularly poignant line.

Released at the height of the civil rights movement, “Mississippi Goddam” represented Simone’s turn toward advocacy through music that would become a lifelong objective. Other protest songs like “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” “Four Women,” “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” followed. Performing jazz, blues, gospel and folk music with her own compositions and classical influences, Nina Simone, in tone and approach, resembled no other artist of the day.

Her vocal talents are the most unique thing about her. Listen to the way she scats on the end of “Feeling Good” or “I Put a Spell On You.” She can reach the higher registers, and the lows. Her voice is rich and sophisticated, deep, commanding and strong, yet sad and heavy with emotion. Her powerful vibrato, wound tight, is unlike so many other artists—perhaps Lauryn Hill or Tracy Chapman could compare. (Listen to Lauryn Hill’s cover of “Feeling Good” for evidence of that.)

She can set the tone for a song through her vocals alone. On sultry songs like “I Put a Spell On You” she’s sassy; on “Brown Baby,” a love letter to an infant girl, her voice is reserved yet full of feeling, and even hope. On “Work Song” she sounds weathered, but determined to break her chains. Her broad knowledge of genres nearly guarantees she’s performed a song that you know and love, and a wide range of artists have known about her versatility for years. Jay-Z used her piano hook on “Four Women,” and cut and skewed her vocals to help form the basis for “The Story of OJ.” Kanye West also manipulated Simone’s vocals on “Blood On the Leaves.”

Despite her immense talent and the influence she imparted on jazz, pop, R&B and soul artists who came after her, Simone struggled in her own life to find the equality she sang about so intensely. At her first piano recital in North Carolina at the age of 12, Simone refused to play until her parents, who had been relocated to the back, were returned to their seats at the front of the hall.

“It was my first feeling of being discriminated against,” she said years later. The incident marked what was possibly Simone’s earliest form of civil rights.

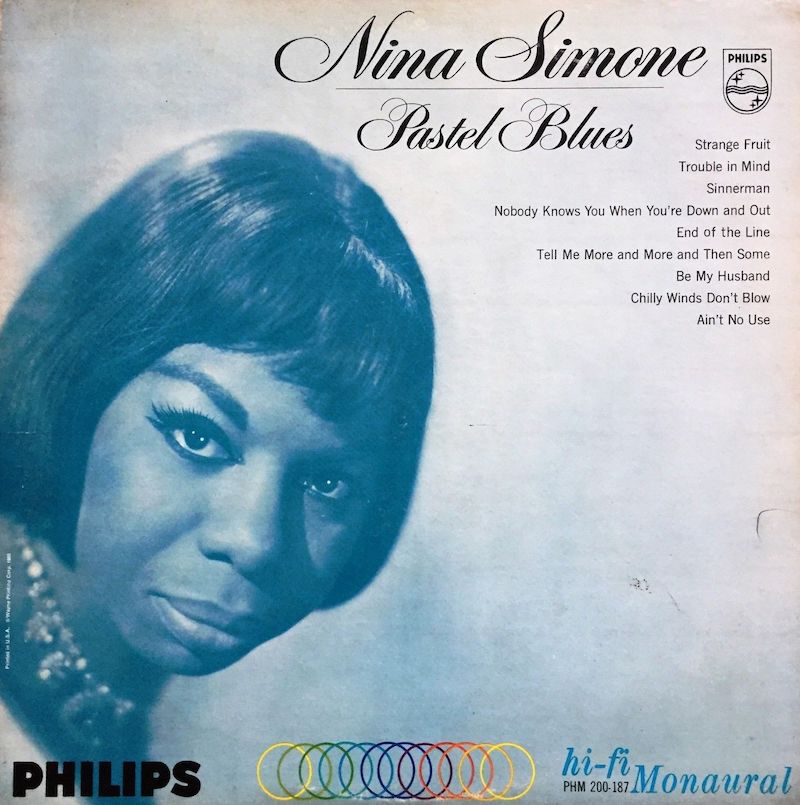

Pastel Blues is a landmark album of the 1960s and of Simone’s career, reflecting the ongoing civil disobedience she nurtured. It’s also an example of how masterfully she could combine elements of modern jazz with blues and spirituals. She effortlessly bookends more restrained standards like “Ain’t No Use” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” with heavier, gut-wrenching songs like “Strange Fruit”—a passionate and vivid cover of the standard made famous by Billie Holiday, protesting the lynching of Black Americans—and a 10-minute-long version of the African-American spiritual “Sinnerman” that strikingly closes the album.

From the start, Simone establishes that the album should be viewed through an abstract lens. The a cappella opener, “Be My Husband,” begins with a beat that seems to materialize from the air, which is endlessly disorienting. Interspersing harsh drum slaps with hand claps to sound like frantic raps at a door, Simone offers to play the domestic role while fending off a threat—“Rosalie,” whom Simone already suspects is the homewrecker. “Please don’t treat me so doggone mean,” she pleads to her betrothed, forcing her words under her breath. “Be My Husband” seemingly boxes her within the social and romantic norms women are still expected to follow. Pastel Blues opens with a trap door.

“Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” has her sinking even further into desperation, trading “bootleg liquor and champagne” for endless misfortune and loneliness. That Simone chose the mournful “End of the Line” as the album’s third song reflects just how low she’s already gotten. Still, she musters the courage to say, “I hope your dreams turn out fine.” It’s a delicate goodbye to a failed relationship.

In “Trouble In Mind,” Simone seeks solace in God, the river, and a rocking chair, and dreams of her worries dissolving with the vanishing clouds. “The sun’s gonna shine in my backdoor someday,” she promises. Through sultry piano notes, a creeping bass line, and a shaking harmonica, Simone again asks for a way to fill the void on “Tell Me More and More and Then Some.” “From now on, to Doomsday… I never will get enough,” she seems confident.

The live 1964 version of “Chilly Winds Don’t Blow,” expresses hope for the future and an end to a troubled existence. It’s a rare silver lining among this collection of out-of-luck blues. As if on a carousel, “Ain’t No Use,” brings her back around to the realization that another relationship has ended. We don’t know whether she’s singing about someone from a previous track or if it’s a fresh loss, but it’s Simone at her most emotionally exposed.

Two of her most famous musical interpretations lead the stunning and devastating finale. “Strange Fruit,” one of the earliest and most successful protest songs, was first dramatically performed by Billie Holiday in 1939, giving life to Abel Meeropol’s stark poem describing lynchings in the American South. Where Holiday filled each word with despair, Simone’s “Strange Fruit” throws a stark spotlight on America’s racist core. With painstaking care, Simone enunciates what happens to those bodies hanging in the trees. Tossed aside and left for nature to reclaim, they slump, get sucked by the wind, become rotted by the sun and swelled by rain, and eventually drop to the ground like so many dead leaves. Every solitary piano note strikes represents a branch of this poison magnolia tree.

A bolder successor to “Mississippi Goddam,” “Strange Fruit”represents her turn from blind outrage to a disturbingly quiet feeling that change remains out of reach. The biblically dire, emotionally charged “Sinnerman” is about one man’s journey as Judgement Day burns. As a child, Simone learned the words to the spiritual while at revival meetings. Endlessly running through a desolate landscape, the sufferer is offered no respite or shelter, just a distant horizon that never arrives.

But the real strength of “Sinnerman” lies within its musicality. The ticking pattern of the cymbals creates urgency and maintains the song’s frantic pace. As Simone and her band repeat the word “Power!” in a call-and-response style, the word becomes a gospel meditation on the awesome power of a Lord who’s been scorned.

Simone’s continuing pleas to God go unanswered as she delivers a rush of classical piano notes that collide, break apart, and finally fade.