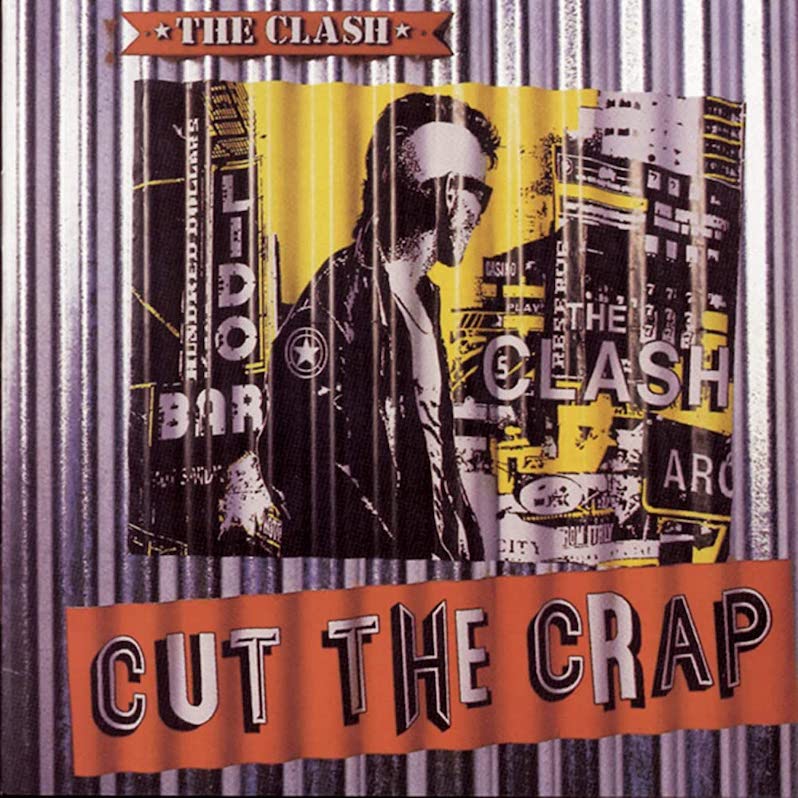

How Cut the Crap brought The Clash to a screeching halt

Although The Clash are generally known as a punk band, only two of their albums—their self-titled debut, and its follow-up, Give ‘Em Enough Rope—have a classic punk rock sound. Both were decent records in their own right, but it wasn’t until 1979’s London Calling that the band fully lived up to their potential as musical trailblazers. Coursing through that record is a powerful, melancholic commentary on rampant commercialism, racial tension and media-fuelled apocalyptic hysteria that gripped Britain in the ’70s. But its political tenor was matched with instrumentation that drifted from traditional punk into more of a genre free-for-all. This trend was only intensified by the band’s trip to New York in 1981, prompting them to incorporate sounds from the burgeoning hip hop scene into their new music. The resulting record was Combat Rock—exuberantly funky, effortlessly danceable, and savagely critical of the Vietnam War and its aftermath. Come for the critique of American imperialism, stay for the basslines!

The Clash’s inimitable knack for songwriting that encompasses an ambitious range of sounds while adhering to an anti-establishment ethos had a particular driving force: the relationship between its two lead songwriters, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones. While the latter introduced the band to then-brand-new genres and scenes, granting them a perpetual forward momentum, the former produced lyrics that grounded them in substance. This dynamic ensured Strummer’s politicism never descended into the generic bellowing that ensnared so much of the punk movement as it fizzled out in the ’80s, while Jones’ poppier inclinations became tethered to a sense of purpose that prevented him simply chasing novelty for its own sake.

This equilibrium worked perfectly, but not indefinitely. Tensions rose, creative differences became ideological schisms, and by the mid-’80s, a winning formula had gone sour with The Clash’s sixth and final album, Cut the Crap.

In September 1983, Strummer and bassist Paul Simonon kicked Jones out of the band. Jones’ expulsion occurred not long after that of the Clash’s drummer, Topper Headon, and one might think that such instability would give the remaining members pause. Far from it: The Clash continued touring with substitute musicians, and announced just over a year later that they were about to record a new album.

This was massive. Imagine if John Lennon had kicked McCartney and Ringo out of the Beatles in 1968, roped in some unknowns, and then gone off to make Abbey Road. But even a Beatles analogy somewhat numbs the enormity of the scandal, which was that the Clash—“The Only Band That Matters”—had booted out a founding member and core catalyst for their success, and then turned around and set about making new material without so much as batting an eyelid.

The reasons for Jones’ departure are varied, but it was, chiefly, because the nuts and bolts of his and Strummer’s musical synergy had broken down. His interest in dance and hip hop (usually an asset) began to grate on Strummer and Simonon (“I used to get on their nerves because of it, a bit, because I was so enthusiastic about it,” Jones admitted in the documentary The Rise and Fall of the Clash). Combined with what Strummer deemed sell-out behavior—dating attractive models and flaunting his cash like some kind of decadent capitalist—the general impression was that Jones had drifted too far from what Strummer saw as The Clash’s mission statement.

Likely the final straw, however, was Jones’ long-running feud with the Clash’s on-and-off manager, Bernie Rhodes. Originally fired in 1978, Rhodes was re-hired just before the recording of Combat Rock, to the chagrin of Jones, who especially disliked him. By some accounts, Rhodes’ aim was to join the band itself. Although he never got that far, Jones’ absence left the position of the band’s primary songwriter (Strummer was more of a lyrics man) wide open.

Before the album’s release, Strummer insisted in interviews that The Clash were set for a revival of the rougher, meaner sound emblematic of their early records, which was hard not to see (at least on some level) as a repudiation of Jones’ flamboyance. The stage was being set for the band to return—under Rhodes’ guidance—as a stripped-back punk rock outfit, and for Cut the Crap to be a sonic throttling of Thatcher, Reagan, colonialism, the pop music industry, and whomever else Strummer considered deserving of his righteous fury.

To say that it fell short of expectations is, if anything, exceptionally diplomatic. The opening track, “The Dictator,” dashes with brutal efficiency any hopes that Cut the Crap might fulfill its promises. It begins with a flurry of synthesized drum beats, which raise some alarm bells. But “The Dictator” seemed to anticipate this, and pre-emptively raises some of its own. The song is punctuated throughout with a shrieking synth-horn that blasts through the mix without any measurable adherence to any kind of rhythm. It’s like being hunted in open water by a shark whose presence you can only determine via the rapid vanishing and reappearance of its dorsal fin. A keyboard horn section and a drum machine in lieu of the real thing don’t exactly scream back-to-basics punk rock, and yet it’s in this vein that the record continues for its duration.

Track four, “Are You Red..Y” features more percussion presumably programmed by somebody kicking the drum machine down the stairs, and the resurgence of more hits of synth that crash into the song with all the grace of an aerial bombardment. “We are the Clash” with its warbling pre-chorus riff and group-vocal refrains, sounds incongruously jaunty, more like a children’s TV show theme than anything you might expect from the band that gave us “White Riot” and “Know Your Rights.” The chorus from “Movers and Shakers” is inundated with yet more synth-horns extravagant enough to serve as the fanfare to a royal procession—not quite the hard-hitting filth that Strummer had been promising months earlier. An album promising to cut the crap had ended up full of it, and the blame for this astonishing sleight of hand has, according to numerous accounts of those involved, been laid squarely at the door of one Bernie Rhodes.

Tragedy struck Strummer in 1984 as his father’s death coincided with his mother’s diagnosis with terminal cancer. Understandably, he abdicated himself from the album process; Rhodes ruthlessly exploited this vacancy, and his efforts to seize complete control (rimshot) of the band bore fruition. He had already seized full authority of his renewed managerial role, dictating what clothes the band were allowed to wear or what drugs they were allowed to take. All the new recruits were bullied, though it was Pete Howard, the new drummer, who got the roughest deal.

What motivated Rhodes to move so radically against what Strummer had been claiming in interviews—such rhetoric, after all, had been pre-arranged with and agreed upon by Rhodes himself—is anyone’s guess, but there is a savage irony in the fact that, having expelled Jones for being too commercial, Rhodes ensured that the Clash’s only post-Jones album would be the furthest thing from punk that they’d ever release. As far as Rhodes was concerned, it seems the only problem with The Clash’s foray into more danceable forms of music was that he personally wasn’t leading the charge.

The one positive remark to be mustered about this desperate free-fall into extinction (the Clash disbanded shortly after the album’s release) is that the guitar tone isn’t half bad. It’s a raw, heavy fuzz, and really could be the sound of a group of angry punks ready to cut through society’s bullshit and tell it like it is. But that doesn’t mean much when it’s backed by percussion that sounds like 60 marbles in a washing machine and aggressive spikes of synths and sampling that flare up almost at random.

We can’t access the alternate universe where Jones never left The Clash. But we can peek through the keyhole. In 1986, Jones’ post-Clash band Big Audio Dynamite released No. 10, Upping Street; five of its nine tracks were co-written with Strummer. The record embraces dance and new wave—programmed drums feature throughout—suggesting a Jones-influenced Cut the Crap might have taken a similar direction (albeit one employing drum programming techniques that amount to more than simply hitting the machine with a hammer). There’s also the ambitious fan-edit of Cut the Crap, composed by German musician Gerald Mann. Applying Strummer’s original vocals to re-recordings of the songs Mann based off demos and live recordings, we get a sense of Cut the Crap as it existed before Rhodes butchered it, and the improvement is both tragic and completely astonishing.

In 2002, Jones and Strummer finally played together on stage again for the first time since 1983, only a few months before Strummer’s untimely death at 50. Meanwhile, Cut the Crap has been, fittingly, cut from the band’s compilation albums (save a few that include “This Is England” as a generous nod to the wreckage). Which is for the best. As far as diehard fans are concerned, The Clash died in 1983, at the same time Jones and Strummer’s relationship did (no affront to the replacement members, all adept musicians sorely let down by tyrannical management). Cut the Crap is a dire warning of what can happen when a group’s collaborative spirit is seized by a dictatorship.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.