Jenny Hval : Apocalypse, girl

Let’s talk for a minute about that title. Apocalypse, girl doesn’t quite invoke a gut reaction in the same way that Jenny Hval’s 2011 album Viscera does. Nor is it as straightforwardly provocative as the title of 2013’s Innocence Is Kinky, which draws a defiant line in the sand. In fact, with its lack of a second capital letter and that comma, Apocalypse, girl seems hardly as confrontational as we’re used to from the Norwegian singer. And what does it mean?

To hear Hval tell it, as she did in a revealing Pitchfork interview earlier this year, it’s both a reclamation of the concept of the apocalypse—a concept that she saw as hyper-masculinized by the metal genre—and the total breakdown and rebuilding of what had defined her music to date. That’s all true of Apocalypse, girl, which features the recurring image of flaccid penises—be it through the rotting bananas she holds in her lap in “Kingsize,” or the “soft dick rock” genre she seems to be trying to create with this album. The constant quest to prove male virility is not so much a threat as it is an annoyance to Hval. On “Take Care of Yourself,” she pleads for intimacy with a male partner, but without the necessity for associated sexuality. You can tell by her tone that her expectations aren’t high.

But that exploration and critique of being “macho” is only one of a multitude of themes that Hval explores on this album, her third released under her own name (two earlier efforts were released under the pseudonym Rockettothesky, and last year saw the release of Meshes of Voice, a collaborative effort with Susanna Wallumrød). Hval also explores the sort of body horror that Western culture seems eager to perpetuate—a fear of our own bodies that seems designed to push us toward capitalist consumption. Displaying weakness or softness, she argues on tracks like the interstital “Some Days,” has been equated with opening oneself up to decay. Remember those rotting bananas?

On “That Battle Is Over,” the album’s hardest-hitting track, Hval takes aim at (capitalist) forces that can declare things about her life and expect them to be taken as truth. “You say I’m free now / That battle is over,” she sings, her voice loaded with sarcasm, “and feminism’s over and socialism’s over/ Yeah, I say I can consume what I want now.” If capitalism is what governs how we view our bodies and our sexuality, Hval seems determined to martyr herself against it. “I’m 33 now,” she whispers on “Heaven,” another standout from the album. “That’s Jesus-age.”

But what Hval sees her sacrifice as being remains kaleidoscopically hard to pin down. Perhaps that’s intentional—for songs like the addictively catchy gender dysphoria anecdote “Sabbath,” she seems content to make us question any norms, or at least to depict personal subversions of them. Musically, the album strays further into the experimental than Hval has ventured on previous releases. “Kingsize” is all jarring, ambient noise, while “White Underground” is an exercise in angular, dissonant harmonies with no discernible structure other than an ethereal white-noise hum.

The music is clearly subservient to Hval’s lyricism—unlike Innocence Is Kinky, which balanced the scales more evenly with melody—and when Hval chooses to imbue her songs with anything resembling a pop structure, such as with “That Battle Is Over,” “Heaven,” or “Sabbath,” the results are some of her strongest works to date. When she doesn’t, the weight rests on her words, which are opaque enough to require poring over. Trying to understand the connections that Hval is making between her lyrical themes is half of what gives this album such replay value. The other half is connecting those to their sonic backgrounds, which can be considerably more trying (though when it works, like on ten-minute outro “Holy Land,” it’s really rewarding).

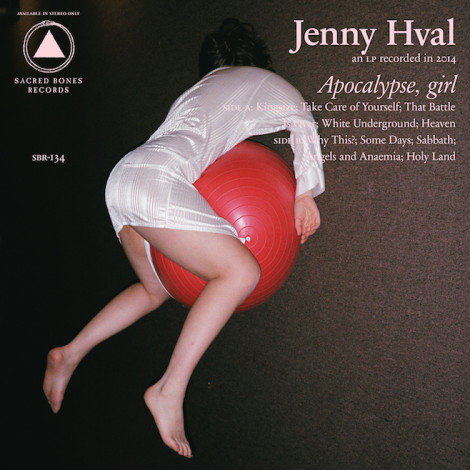

So back, then, to that title, Apocalypse, girl, a combination of words and punctuation as apparently impenetrable as the rest of the album. What does it mean? Looking at the title within the context of the album art—with the matter-of-fact placement that has become standard for releases from the Sacred Bones label—it seems almost like it’s positioned as Hval’s title, her occupation, a fact that’s truer on this uncompromising album than on any other entry into her discography. She’s a girl, sure, but mostly she’s an Apocalypse.

Similar Albums:

Julia Holter – Loud City Song

Julia Holter – Loud City Song

My Brightest Diamond – A Thousand Shark’s Teeth

My Brightest Diamond – A Thousand Shark’s Teeth

Braids – Flourish//Perish

Braids – Flourish//Perish