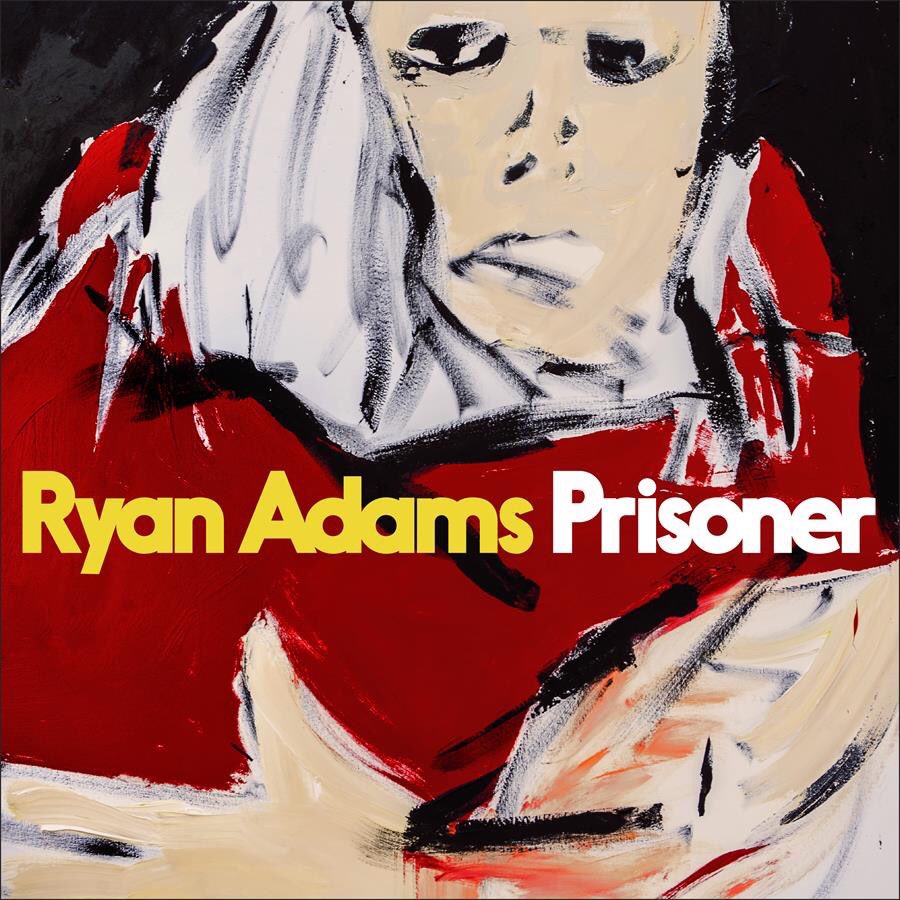

Ryan Adams : Prisoner

It’s been 17 years since the release of his first solo album, and Ryan Adams still can’t get certain fans and critics to stop bringing up Heartbreaker. You’d think this would be a good thing: It’s one of the best-loved singer-songwriter records to come out in the past 25 years. But the former Whiskeytown bandleader has released more than a dozen albums since then: most are solid, a few nearly as great. None are Heartbreaker, including his latest solo record, Prisoner. That shouldn’t matter, and regarding Prisoner’s overall quality, it doesn’t—but that won’t stop people from bringing it up.

Nevertheless, this album is in the higher echelon of Adams’ work. It showcases the effortlessness with which he creates songs and arrangements that draw you in. Think of the start-stop progression of “Do You Still Love Me,” how its mournful organ riff prepares you for the impending guitars in a way that makes perfect sense, or the austere riffing and vocal mini-glissandos in the pre-choruses of “Haunted House” that make it seem like a huge hook is coming but don’t prepare you for the forlorn, subdued refrain. Prisoner is lousy with such emotionally wrought musical moments. (It doesn’t hurt that sobriety has turned Adams into a complete studio whiz who produces his own work.)

This may be the first album in which Ryan Adams has directly invited Heartbreaker comparisons. Not in sound or genre so much as theme: It’s a breakup album, and Adams instinctively understands and interprets the facets of heartbreak with greater honesty than all other feelings. The drumless, clean-electric strum of “Shiver and Shake,” sounding like an evil twin to Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m On Fire,” sets the stage for lyrical devastation: “Close my eyes; I see you with some guy/Laughing like you never even knew I was alive.”

It gets more painful from there, in that song and as the album progresses. “Anything I Say To You” would be a guitar-pop anthem if not for its complete brokenness, while “Doomsday” finds Adams revisiting the ’70s radio country-rock sonics of Gold and Cold Roses. Nowhere can he find relief or solace from the pain. By the time “Tightrope” comes around (the only song to ape the sparse country tone of Heartbreaker), he’s pleading, begging for his heart to be unbroken, begging himself to have not fucked up the things he fucked up. It is so deeply sad that the saxophone solo after the second chorus, despite being an initial surprise, is an appropriate coda. It represents acceptance—instead of begging the relationship to return, Adam is playing “Taps” for its funeral and mourning it. Every person who’s ever been dumped eventually reaches that point, where they accept it and move on, in part if not whole. “We Disappear” closes the album with a reminder that while the pain isn’t gone, life will proceed from here for him and his lost lover, and he genuinely wishes for her happiness. (Side note: This album is about his divorce from Mandy Moore, which makes the scoreboard Actresses 2, Adams 0.)

There are some identifiable inspirational touchstones to this record. A lot of people might say Tom Petty, and they won’t be wrong (it’s just that Adams does Petty better than Petty; yes, you can catch me outside if you disagree because Tom Petty is boring as hell.) Jokes aside, I immediately thought of Springsteen’s Tunnel of Love, an album in which a man can’t figure out what to make of love and domestic happiness and is waiting for the other shoe to drop. Prisoner sounds like what Tunnel would if Bruce didn’t stop at the uncertain “Valentine’s Day” and wrote songs about the collapse in all its unvarnished horror.

But rest assured: Ryan Adams, by now, has a sound that is distinctly his. You can determine the antecedents but the resulting work never feels derivative. I’ve come around to thinking that while Adams might never get out from under Heartbreaker’s shadow in the minds of some, it doesn’t matter. Whether he’s indulging the outer limits of his tastes to make impromptu punk EPs (1984, the truly bizarro Vampires), dropping flawless unannounced country blues singles like “I Do Not Feel Like Being Good,” or hunkering down for concentrated album-length statements like Prisoner or his underrated 2014 self-titled, Adams only answers to his own muse and is better off for it.

Similar Albums:

Bruce Springsteen – Born in the USA

Bruce Springsteen – Born in the USA

The War on Drugs – Lost in the Dream

The War on Drugs – Lost in the Dream

Jenny Lewis – The Voyager

Jenny Lewis – The Voyager