10 Essential Spiritual Jazz Albums

Spiritual jazz begins, essentially, with John Coltrane. In 1965, he achieved a state of transcendence with A Love Supreme, one of the greatest expressions of the contents of one’s soul ever to be captured on tape. And in the final few years of his life, Coltrane found himself pursuing the mysterious and transcendent via groundbreaking releases such as 1966’s free-jazz free-for-all Ascension and Eastern-influenced experimentations like Om. It opened up a new world of exploration for jazz, which found like-minded artists such as Pharoah Sanders and Don Cherry taking similar tacks to reach toward the transcendent through compositions that fused the intensity of free jazz with motifs from African and Indian music, creating sounds both passionate and tempered, meditative and primal. Spiritual jazz is often more about a feeling than a specific approach, but with Easter just ahead of us, we’re turning to the music that speaks to something beyond our earthly understanding. Take a trip through some deeply soulful and mystical masterpieces with our list of 10 essential spiritual jazz albums.

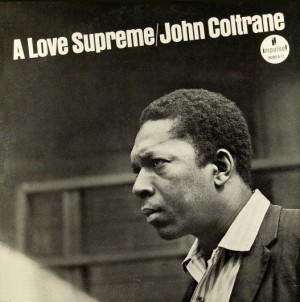

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

(1965; Impulse!)

His discography and legend implant in music fandom a false memory of John Coltrane as a sax oldhead who was around forever. The reality is that this scion of jazz died far too soon; liver cancer felled him at the age of 40, just two years following the release of this masterpiece. Every chapter in Coltrane’s book of life is therefore shorter than we recall, which makes the one written around A Love Supreme that much more vital. Coltrane’s drinking and drugging cost him a regular gig with Miles Davis in 1957, and he spent the next seven years looking to God to help him fight his demons. He saw redemption in the birth of his son, and composed a message of thanksgiving in a marathon five-day writing session in 1964. His wife Alice recalled him coming down the steps of their house holding the notes for this album like Moses bringing stone tablets from Mount Sinai. The results may not have comprised the first spiritual jazz album but they likely made the perfect one—arranged like a covenant, at times chanted like a prayer, its main motif played in every key possible to emphasize its universality. – AB

Philip Cohran and The New Heritage Ensemble – On the Beach

Philip Cohran and The New Heritage Ensemble – On the Beach

(1968; Zulu)

The most poignant spiritual jazz is sometimes that which evokes a feeling more than any outright statement of intent. That’s ultimately what faith is—a belief in something that’s not there in front of you, but whose presence can be felt deep within. On the Beach is just that sort of record, melding styles and backgrounds into an eclectic and powerful creation of improvisation and jazz composition alike. Philip Cohran had previously played with the great Sun Ra and was an early performer with Earth, Wind and Fire, and On the Beach bridges the two in a way. It’s funky, it’s cosmic, it’s bold and Afro-centric. Many of the tracks feature prominent use of Mbira (an African thumb piano), which adds a uniquely African sound to the tracks, which lean from a deep groove on one end to a raga-like drone on the other. It’s a wide range of expression, but it’s all stunningly expressed and built up into something majestic. – JT

Sonny Sharrock – Black Woman

Sonny Sharrock – Black Woman

(1969; Vortex)

The title track of Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman is somewhere between the soulful feeling of gospel, an exorcism and the seemingly alien experience of hearing someone speak in tongues. It’s like hearing someone completely lose sense of self and express a deep and piercing interdimensional broadcast from deep within the soul. That experience is courtesy of vocalist Linda Sharrock, Sonny’s wife, who countered his discordant, intense guitar shrieks with something more human, and at times aggressively, ferociously so. This is as loud and throttlingly confrontational as spiritual jazz gets. It’s just one piece of a greater avant garde whole, however, whose style speaks more to the likes of Sonic Youth and The Velvet Underground than Wes Montgomery or Grant Green. It’s not quite noise jazz, but it’s on a plane unto itself. – JT

Alice Coltrane – Journey in Satchidananda

Alice Coltrane – Journey in Satchidananda

(1970; Impulse)

Alice Coltrane’s spiritual journey started from a place of grief. After the death of her husband, John Coltrane, she underwent a period of personal struggle that found her unable to sleep and losing weight. The pain in her personal life led her to spiritual practices, following the guidance of Indian guru Swami Satchidananda, whose name appears on what’s arguably her best album. Heavily influenced by Indian ragas, the album blends jazz percussion with sitars and Coltrane’s own dazzlingly psychedelic harp playing, as well as Pharoah Sanders’ phenomenal saxophone solos. There’s an ode to the “realm of Shiva” in “Shiva-Loka,” while “Something About John Coltrane” is a track based on the music of her late husband, and there’s an overarching sense of profound beauty throughout it all. Even for the secular listener, this is an album that speaks of something beyond this realm. – JT

Albert Heath – Kawaida

Albert Heath – Kawaida

(1970; O’Be)

The personnel on Albert “Toodie” Heath’s 1970 album Kawaida is pretty remarkable on its own, including such legends as Herbie Hancock and fellow spiritual jazz pioneer Don Cherry. As Heath is a drummer, naturally, the album is heavily rhythmic, the blend of his drums and Mtume’s congas providing a breathtaking, soulful backing for a psychedelic swirl of hypnotic, Afro-centric, momentous and pulsing jazz with a heavily physical presence. There’s a restrained groove about it at times, such as on the 13-minute “Maulana,” but the ensemble is often reaching toward something greater and more intangible, as with the ascendant notes of Jimmy Heath’s saxophone on opening salvo “Baraka.” It’s a highly different form of spiritual jazz than, say, John Coltrane’s chaotic Ascension. The feeling here is intense, but it’s also one that you wouldn’t have a hard time dancing along with. – JT

Pharoah Sanders – Thembi

Pharoah Sanders – Thembi

(1971; Impulse)

Of the many albums that Pharoah Sanders released on Impulse between 1966 and 1973, just about any would have a place here, all of them masterful works of powerful avant garde jazz, imbued with a heavy dose of spirituality. Thembi stands out, however, for being the most meditative of the bunch. It’s almost like ambient jazz in a way, with only certain parts of it escaping the low-key groove in favor of a righteous intensity (“Red, Black & Green”). Its key track is the opener, “Astral Traveling,” which can be heavily attributed to keyboardist Lonnie Liston Smith, both for his experimentations with Rhodes piano and astral projection. The result is a cosmic epiphany. – JT

Rahsaan Roland Kirk – Prepare Thyself to Deal with a Miracle

Rahsaan Roland Kirk – Prepare Thyself to Deal with a Miracle

(1973; Atlantic)

“It’s about time we started checking out our miracles—our beautiful, black miracles.” The invocation that opens “Saxophone Concerto,” the final and longest track on Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s late-career gem Prepare Thyself to Deal with a Miracle is both a blessing and a mission statement. Prepare Thyself, a structured and composed work of avant garde third-stream jazz, is a document of miracles in action. Kirk, an experimental and incredibly talented jazz legend, would play several horns at once, which in itself feels like something of a miracle. But by this stage, his music had transcended hard bop and entered a phase of atmospheric, soulful composition that was simultaneously joyful and strange, balancing moments of melodic vibrancy with minimalist drones. Its two greatest moments are its two longest, “Seasons” and “Saxophone Concerto,” each of which displays a breadth and versatility that many artists wouldn’t attempt in an entire album, let alone a sole composition. It’s miraculous. – JT

Don Cherry – Don Cherry

Don Cherry – Don Cherry

(1975; Horizon)

This self-titled album (later retitled Brown Rice) is akin to Pharoah Sanders’ Thembi. It’s a work that provides a strong entry point for first-time listeners, although Cherry’s discography can arguably have a steeper hill to climb for first-timers than Sanders’. This album, however, is accessible, low-key and hypnotic. Its musical motifs are heavily inspired by Eastern sounds, in particular the 14-minute standout “Malkauns,” which is based on a traditional Indian raga. The name means “he who wears serpents like garlands,” referencing the god Shiva, and Cherry’s interpretation builds and unfolds in dazzling fashion. Yet on the easier grooving title track (itself a sort of spiritual paean to a centered diet) and “Degi-Degi,” Cherry also offers a funky, ambient counterpoint that’s meditative and pleasing in its own right. – JT

Steve Reid – Nova

Steve Reid – Nova

(1976; Mustevic Sound)

Steve Reid’s Nova is a deeply soulful record. Its title track is built on a buoyant burst of piano that evokes traditional African-American gospel music, while the more hallucinatory “Lion of Juda,” referencing the Biblical icon of the Tribe of Judah and common motif in Ethiopian iconography, balances laser-beam keyboard solos with a bassline that seems to predict Fugazi’s “Waiting Room.” Though most of the compositions are relatively brief by the standards of jazz’s more avant garde side, they contain a vastness and openness that speaks to something beyond the musicians playing in the room. When “Free Spirits—Unknown” arrives, they achieve something spectacular, a steady bass pulse in the background providing a launchpad for the realization of something eerie and mystical. Something, perhaps, even divine. – JT

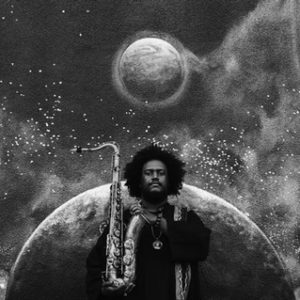

Kamasi Washington – The Epic

Kamasi Washington – The Epic

(2015; Brainfeeder)

Kamasi Washington brought spiritual jazz back to popular consciousness on a wider scale in 2015 with the release of his ambitious, aptly-titled triple album, The Epic. A far-reaching and eclectic sonic document that follows an abstract narrative of a samurai’s journey, the album carries a theme of personal achievement and enlightenment on a non-religious scale. Yet the addition of a choir on many of its tracks ends up turning the L.A. saxophonist’s compositions into works of interstellar gospel. So on a track like the breathtaking opener “Change of the Guard,” Washington channels the soul of Sun Ra and Pharoah Sanders at their most transcendent, tapping into a universal consciousness through melodies with a modern appeal. – JT

How do you leave Eddie Gale’s “Black Rhythm Happening” off this list. Trane and Eddie were tight. And all the Arkestra projects? Eddie rode with Sun Ra.

Imagine the tonal improvisers trying to hang with the free improvisers. Eddie was one if the few that did.

I feel like a Charles Lloyd album belongs here. Like Fish Out of Water or Canto. Just a thought.