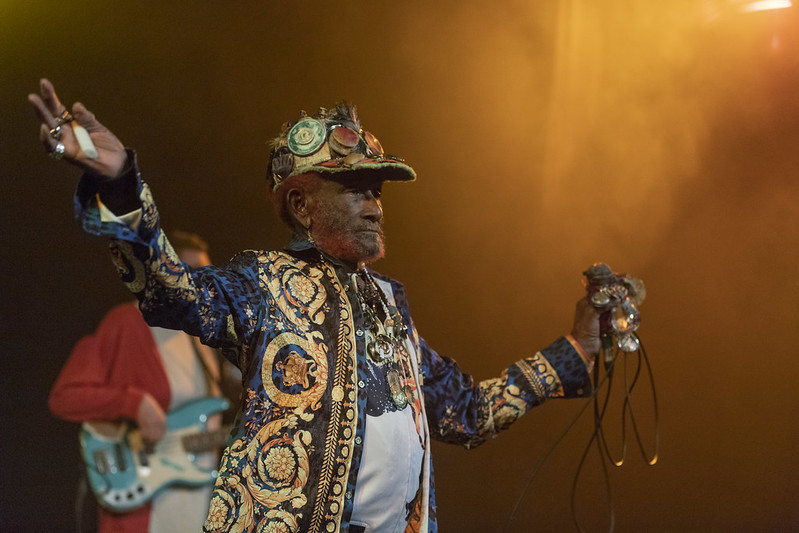

A Beginners Guide to dub pioneer Lee “Scratch” Perry

“If you have good music, you have good magic.”

Lee “Scratch” Perry has a way with words. These words in particular, spoken to The Guardian on his 80th birthday four years ago, summarize well the kind of accessible mysticism that the reggae icon and dub wizard has wielded over his 50-plus-year career. If you’ve listened to a reggae album, a dubplate, even much of the vast world of electronic music in the past 40-50 years, you’ve heard music that’s been touched, influenced or shaped in some way by Perry. Whether in his early innovations on some of dub’s earliest recordings, or through his production work for the likes of Bob Marley, Max Romeo, Junior Murvin or The Congos, Lee Perry changed the shape of both Jamaican music and popular music at large.

Rainford Hugh Perry was born in 1936 in Kendal, Jamaica, and began recording tracks at Studio One in Kingston in the ’50s, where he also laid down his first recordings of his own. His earliest recordings were mostly ska tracks, as later collected in the 1989 reissue Chicken Scratch—the title of which is how he earned his nickname “Scratch.” Yet it wasn’t until he formed his own label, Upsetter Records, and formed The Upsetters that Perry began to flourish as a creative force in Jamaican music, releasing on average two or more albums per year credited to either himself or The Upsetters. And in 1973, when he built his home studio, The Black Ark, Perry entered a new phase of innovation and high-profile production that yielded both many of his best known albums and his most radical creations.

The Black Ark takes on a kind of mythical quality when viewed through the lens of history—the site of a long list of legendary recordings, given an added dose of magic through Perry’s unconventional and sometimes mystical techniques. He employed multi-track recording in a way that few other dub producers didn’t, creating layers upon layers that gave his recordings a frequently impenetrable density. At other times, there was an ineffable, spiritual quality to his approach, like blowing smoke into microphones, or burying mics beneath the sand at the base of a tree in order to capture an otherworldly bass drum effect. And then there were moments like having a singer “moo” into a cardboard tube wrapped in foil. That Black Ark burned down in 1979, after being covered in cryptic magic marker scrawl from Perry himself, only adds to the strange legend and mystique of the studio. There are various version of why the studio went up in flames, but Perry has taken credit for lighting the spark.

Having just turned 84, Perry now has literally hundreds of recording credits to his name, from his own solo releases, those of The Upsetters, other artists he’s produced and written songs for, and various collaborators over the years, which include The Clash, The Beastie Boys and The Slits’ Ari Up. A catalog that big can be intimidating to dive into; it would take years to catch up. And there are many worthy points of entry, so here’s my attempt to trim it to a strong first five of the best Lee “Scratch” Perry albums and singles, encapsulating Perry the producer, songwriter, studio mastermind and bandleader.

Photo by DONOSTIA KULTURA, Creative Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0]

“Disco Devil”

“Disco Devil”

(1977; Upsetter)

We’re starting not with an album, but with a single that encapsulates Lee “Scratch” Perry’s dub innovations, songwriting strength and tendency toward experimental soundscapes all in one eight-minute duration. “Disco Devil” is, essentially, three songs in one—a dub of Max Romeo’s “Chase the Devil” layered with The Upsetters’ own take, “Croaking Lizard,” and Perry’s own adlibs layered on top. The source material is among Perry’s best productions as it is, but add in the clangs of cowbell, rattles, echoes and plenty of Perry’s own vocal overdubs, and it becomes a dense piece of dub mastery, a moment where the remix, the mashup, and a legendary roots reggae anthem all intertwine.

Listen: Spotify

The Upsetters – Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle

The Upsetters – Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle

(1973; Upsetter)

Speculation abounds over what the first official “dub” album is, though consensus points to Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle—a record originally held to a limited pressing of 300 in Jamaica before it quietly revolutionized an entire sound. As an early document of dub, it introduces a number of elements, including a stereo mix and reverb. But most of all it’s simply one of the coolest sounding dub records of the canon—let alone one of Lee “Scratch” Perry’s best albums—driven by the booming echo of drums and deep, earth-moving basslines. The murkier and weirder things get, the richer the Blackboard Jungle listening experience is, whether through Perry’s voice-of-the-gods toasting that introduces the album on “Black Panta,” definitely the most climatic and intense track here, or the rumbling percussive sound to “Elephant Rock.” Dub, as we know it now, has been updated, polished and deconstructed in the nearly 50 years since. But that being said, every dub record has a little bit of Blackboard Jungle in it.

Listen: Spotify | Buy: Turntable Lab (vinyl)

Junior Murvin – Police & Thieves

Junior Murvin – Police & Thieves

(1977; Island)

It takes some effort to find any shade cast on Junior Murvin’s legendary debut, whose title track is cemented in the popular music canon. But one critique I have seen, warranted or not, is that it’s relatively free of the experimental dub production techniques that define much of his solo work, that of The Upsetters, and even a record like Heart of the Congos. Which I get. But it’s also shortsighted in the face of such a masterful, soulful reggae record defined by its sociopolitical statements (the title track is as true today as it was 43 years ago), gorgeous instrumentation, and of course Murvin’s own falsetto vocals, which have led me to think of him like reggae’s Curtis Mayfield. (The grooves here don’t hurt either.) This isn’t Perry’s most experimental work, but it is one the best to bear his production credit. Moreover, he co-wrote half of the songs with Murvin, and two of them, “False Teachin'” and “Workin’ in the Cornfield,” are Perry originals. Really, though, one need only fire up a track like “Lucifer” or “Roots Train” to hear just how much soul, intensity and stunning layers of sound there are to this record.

Listen: Spotify | Buy: Amazon (vinyl)

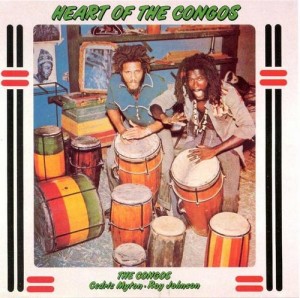

The Congos – Heart of the Congos

The Congos – Heart of the Congos

(1977; Black Art)

There are elements of Heart of the Congos in other works that Perry had produced prior—the deep spiritual element in Max Romeo’s Chase the Devil, lush and hypnotic arrangements in Junior Murvin’s Police & Thieves, hypnotic vocal harmonies in his work with The Heptones. It’s in how all of these elements come together that make Heart of the Congos the transcendent cult classic it’s become. A roots reggae record steeped in the space-age effects of dub at its best, The Congos’ debut is at once deeply moving and transformatively hypnotic. It at times feels like a gritty psychedelic soul record, the shimmering guitars at the opening of “Fisherman” twinkling like distant lights in a narcotic haze, while the percussive pulse of “Congoman” seems to predict the more abstract offspring of dub in the 21st century. Those two tracks were also co-written by Perry, and though The Congos are the marquee performers, what Perry—and an all-star cast of performers, including Sly Dunbar, Ernest Ranglin and Gregory Isaacs—helps to build around their mesmerizing vocals is nothing less than a reggae masterpiece.

Listen: Spotify | Buy: Amazon (vinyl)

The Upsetters – Super Ape

The Upsetters – Super Ape

(1976; Island)

Of the many studio albums to feature Lee Perry’s songwriting and production work, in addition to his band The Upsetters, Super Ape is both the most acclaimed and most well-known—there are other versions of this kind of article on other websites and they probably all feature this album somewhere. And rightfully so. It’s a masterful moment of dub colliding with roots reggae, of warm and earthy instrumentals with man-behind-the-curtain toasting, of lush headphone production with otherworldly sounds and effects. It encompasses the spectrum of reggae and dub, complete with elements of soul and jazz, gorgeous guitar licks and bold punctuation of horns. Super Ape is an easy album to love—how couldn’t you be won over by a record adorned by a spliff-smoking King Kong? I opted to slot this in at the end rather than the beginning, however, not because this is advanced listening (that’s reserved for Perry’s later collaborations with The Orb or Brian Eno) but because it’s easier to get a better appreciation for the sonic depth of this record and all the various surprises it contains within after first taking a longer tour around the Black Ark. “This is the ape man…“

Listen: Spotify

Also Recommended: Once you get started with Black Ark’s “holy trinity,” you have to keep going, naturally. The other two (assuming you’re not counting The Congos, who kind of ended up being retconned into the three, and understandably so) are The Heptones’ Party Time, in which Perry’s spacey production fleshes out some soulful pop-roots harmonies, and Max Romeo’s War ina Babylon, which features the original version of “Chase the Devil,” not to mention a stunning roots album featuring Perry’s production and rich arrangements from the Upsetters. Next hear The Clash’s “Complete Control,” recorded after Perry heard the band’s cover of “Police & Thieves” and agreed to work with them. Obviously, Perry recording punk sounds considerably different than the other material here, but he captures the energy of the band with a bit of extra polish. An early highlight for the band. Next, hear Perry’s own Roast Fish Corn Bread & Collie Weed, a roots album of his own made significantly weirder with songs about eating right and mooing cow sound effects—the right balance of accessibility to zaniness. And lastly, seek out one of Perry’s collaborations with Bob Marley, particularly 1971’s Soul Revolution, whose warm sound isn’t quite the heady hallucinations of Super Ape, but an easy album to love all the same.

Advanced Listening: After digging into the peak of Perry’s ’70s dub productions, go back to the beginning. The Upsetters’ Return of Django is one of the first full-lengths that Perry produced, and its ska/rocksteady instrumentals lean heavy on a spaghetti western motif, as cowboy films (and later kung-fu movies) had a major influence on the themes of his records. After going back to the earliest sounds, transport back to the present, with a couple of notable collaborations. In 2012 he worked with ambient dub overlords The Orb on The Orbserver in the Star House, and on last year’s Heavy Rain, Perry even found a creative partner in Brian Eno on “Here Come the Warm Dreads.”

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.

“Disco Devil”

“Disco Devil” The Upsetters – Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle

The Upsetters – Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle Junior Murvin – Police & Thieves

Junior Murvin – Police & Thieves The Congos – Heart of the Congos

The Congos – Heart of the Congos The Upsetters – Super Ape

The Upsetters – Super Ape

Regarding ‘Complete Control’. Clash guitarist Mick Jones once said in an interview that the Lee Perry mix just didn’t sound right for the band, so after Perry had left he went back into the studio and re-did it himself and that mix appeared as the single. Which probably explains why the recording has no essence of Lee Perry about it whatsoever!

Slightly different is the band’s cover of Pressure Drop which appeared as the B-side of a single. Perry created a mix which (again!) the band didn’t use but which can be found on bootleg.