How the “Black Sabbath” riff captured diabolus in musica

What does evil sound like?

It’s not an easy thing to define. It might be the vintage, malevolent sound of pipe organ in a silent horror movie, or maybe the harsh screech of pure, chaotic noise in power electronics. The speech of authoritarian despots or the incessant jingles of advertisements that grow increasingly more intrusive by the second—on autoplay, coming from a window or an app you can’t seem to find and close out of soon enough.

There’s a more obvious answer, especially to concerned parents in the ’80s and those who wish to harness the power of the dark lord through some sweet guitar licks: Heavy metal. Even more specific than that, it’s the first three notes of the first song on Black Sabbath‘s debut album, a tritone that’s become known as “The Devil’s interval.”

Now, there’s nothing inherently evil about a tritone—it’s a musical interval comprising three whole steps. They’re just notes, in other words, which we, ourselves, choose to imbue with qualities outside of the literal sounds themselves. The sound you hear on “Black Sabbath” is an inversion of a tritone, essentially the same intervals used in a power chord but with the fifth flattened, so as to create a kind of dissonance that feels oddly sinister and interrupts what might be a more natural sounding melody by introducing something uglier and darker. It feels like a step into unseen peril, an unresolved limbo where doom feels all but certain. In that flattened D note (which guitarist Tony Iommi trills back and forth a half step), heavy metal is birthed in dramatic overture.

Black Sabbath didn’t invent “The Devil’s interval” or diabolus in musica as it’s been known in Latin for much longer than rock music existed. Iommi took inspiration from Gustav Holst’s “Mars, the Bringer of War,” and composers like Richard Wagner and Camille Saint-Saëns employed them in their own works. During the Renaissance, using such sounds was roundly rejected as it was an affront to both God and ideals of beauty, which at the time were inextricable.

Naturally, it’s perfect for heavy metal. The devil had made his debut in popular music decades earlier, in the haunted recordings and mythology of Delta Blues, and he pretty much stuck around ever since, generally causing mischief and mayhem in the name of rock ‘n’ roll. Maybe wearing leather and riding a motorcycle with flames on the side, but more likely wearing an Italian suit and claiming ownership of master recordings that will someday burn on a shelf in a warehouse due to general negligence. But the devil is also part and parcel of the whole identity of heavy metal, more or less—witch covens, the number of the beast, or just the general spirit of asking What Would Satan Do?

“Black Sabbath” isn’t that, exactly. When Ozzy Osbourne introduces his lyric with one of the most eerily evocative opening lines ever written—”What is this that stands before me?“—he sounds as if he’s standing face to face with the devil itself, though it wasn’t actually his own experience that he was drawing from, but rather that of bassist Geezer Butler. A budding occult aficionado and Catholic whose belief in the devil was genuine, Butler had begun reading up on Aleister Crowley and Dennis Wheatley, and subscribing to a weekly magazine called Man, Myth and Magic. Plus Ozzy had given him a book about magic from the 16th century, and well, we all know that when there’s some kind of creepy, mystical tome from yore that comes into your possession, some pretty intense stuff is bound to happen.

The experience of immersing himself in the dark arts led to a nightmarish event in which Butler awoke in his bed to find a dark presence in front of him, which scared the hell out of him—so to speak. He immediately tossed aside all the witchcraft and occult objects, but that magic book gifted to him by his bandmate had mysteriously vanished. Had that dark figure taken what was rightfully his? Or did Ozzy stumble into his flat after hours? I suppose we’ll never know for sure.

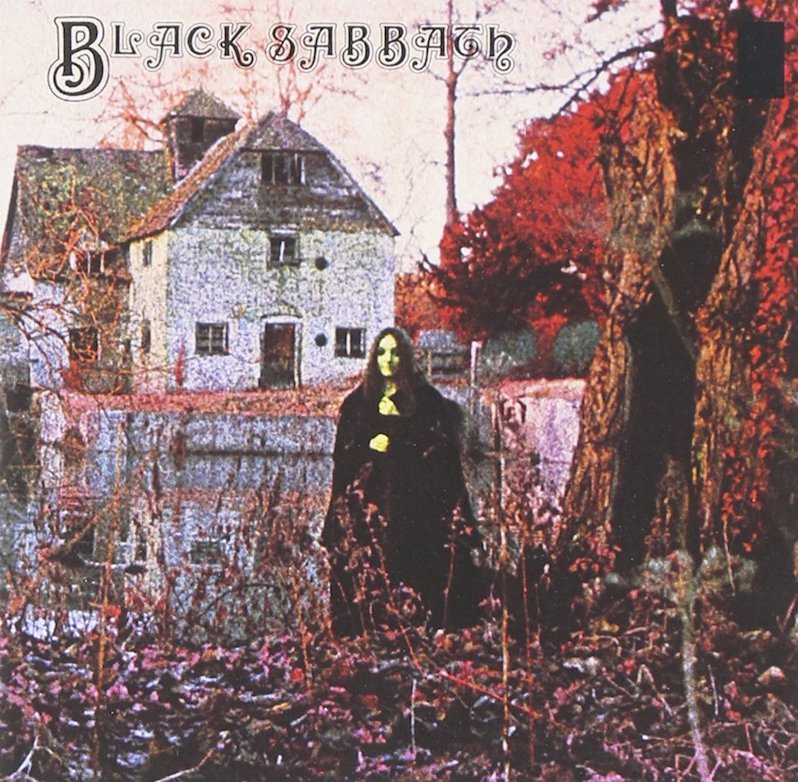

The group attempted to capture that sinister imagery on the album’s artwork, the imagery of model Louisa Livingstone, draped in a black cloak, in front of the Mapledurham Watermill evoking the sort of witchy mysticism that inspired the encounter. The inclusion of an inverted cross on the original inner gatefold certainly pushed that idea forward, though more than anything it served to bring more weirdos to the band’s shows—Sabbath weren’t necessarily all that committed to Satanism as a bit, but that they embraced it at all appealed to a certain kind of audience that followed the likes of Anton LaVey.

But that triad that opens “Black Sabbath” will forever be the sound of heralding of that dark figure, whomever he may be. All hail the riff.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.