Blueprint: How Smart Went Crazy’s ‘Con Art’ broke from D.C. punk tradition

Blueprint is a new monthly feature that takes an in-depth look at influential post-hardcore, art-punk and noise rock albums released in the past 30 years, featuring commentary from the artists themselves.

If one were to attempt to get a handle on what kind of band Smart Went Crazy were within the first three tracks of their 1997 swan song, Con Art, they’d likely come away with a confusing composite of a band. Leadoff track “Black Kites” is a spacious, instrumental slowcore introduction, whereas “Exitfare” is 55 seconds of hard-charging post-hardcore driven by cello, and “A Brief Conversation Ending in Divorce” is a graceful indie rock number that nods to more sedate Slint or Fugazi. It’s a lot to process in only six minutes.

Released during the 15th anniversary year of Dischord Records, and just months before Smart Went Crazy broke up, Con Art is a big statement that still offers a lot to analyze and chew on. A group of musicians who grew up in the Washington, D.C. punk scene that birthed the likes of Fugazi and Jawbox, Smart Went Crazy maintained those bands’ commitment to tuneful experimentation extending from punk’s roots. Yet Smart Went Crazy weren’t committed to being a punk band by anyone’s measure. That they occasionally bore a resemblance to Fugazi was perhaps inevitable, but it was also fleeting. There are 18 tracks on Con Art, and there are seemingly just as many musical directions—all bearing the signature of the musicians driving them, but rarely intersecting on an overt level.

Considering this was only the band’s second album, that’s a pretty big leap to make, though one that was a conscious decision. Former Smart Went Crazy frontman Chad Clark says that the band’s frame of reference for the album included double- and triple-albums by legendary albums such as The Beatles and The Clash—album archetypes that their own label didn’t really have the structures in place to handle on a practical level.

“We had a lot of ideas,” he says. “And it just seemed like the shape was not going to be something small—it was going to be something grand and sort of sprawling. Like the White Album or Sandinista!. We talked about Sandinista! a lot. So, records take different shapes, and the sprawling record is not always the right thing. I generally try to exert more discipline on the form of something. But with Con Art we had a lot of ideas and we wanted to try them all, basically. We didn’t realize at the time that Dischord didn’t have any kind of policy or even pricing for double albums. So we kind of overshot what the label was comfortable with. And that became an issue.”

At 73 minutes long, Con Art isn’t as grand and sprawling as the three-LP Sandinista! that Clark and company envisioned as its ideal, but it’s certainly a lot of music to absorb in one sitting. There are connective threads that make the flow of it more seamless, such as how the sound of Hilary Soldati’s cello bridges “Exitfare” with “A Brief Conversation Ending in Divorce.” Or how the playful “A Good Day” climaxes in noisy, tense guitar jabs, much in the same way that “D.C. Will Do That To You” begins. Oh, and there’s two songs called “D.C. Will Do That To You,” one of which is longer, more spacious and meditative than the other, while the shorter, more punk of the two is a meditation on homelessness in Washington.

If Con Art seems odd in the context of Dischord punk and hardcore, it is—but things were already changing quite a bit in the scene at this time. Jawbox had already broken up, and Fugazi only had a few more years left in the tank. Shudder to Think’s final studio album had been released just months before—on a major label, without much in the way of “post-hardcore” to speak of—and The Nation of Ulysses’ Ian Svenonious had long since moved on to playing soulful garage rock with The Make-Up.

Smart Went Crazy never really thought of themselves in punk or hardcore terms, and as such that gave them the freedom to explore any style of music they wanted. Or, better yet, invent new ones entirely.

“One of the things we always tried to do was to kind of create a genre for a song,” Clark says. “Take the song ‘Con Art,’ which is sung by Hillary. What kind of music is that? That music—that song doesn’t have a genre. It’s not anything you’ve heard before or since. It’s a song that creates its own genre and then it’s the only song in its genre, and then that genre is finished. There are other songs on the record that are like that. ‘Tight Frame Loose Frame’ doesn’t sound like any other piece of music. It wasn’t repeated. It’s not a style we had. We’d make up that type of music and make that one song for that type of music, and that’d be it. That’s sort of a thing that I feel like I still do to this day with Beauty Pill. Where a song that’s in a style that we only visit once, basically.

“We didn’t think about ourselves in the context of punk or hardcore music,” he continues. “We just felt sort of separate from that. The thing about Dischord that I feel like is sometimes not apparent to people who are fans of the label is that you are really free. Ian [Mackaye]’s whole trip is that you are free as a creative person to make anything that comes to your mind. And you are encouraged to explore your imagination or whatever impulse you have. There’s not this sort of, ‘oh you play this style of music that’s already been established.’ Ian would like people to be themselves. That’s to his credit, something i really appreciated about Dischord, that I was never told to make a certain type of music, or given any type of aesthetic boundaries. And I think Con Art is a flowering of that circumstance. I’m proud of the record. I’m glad it has lasted. I’m glad people are still interested in it and talk about it. And that I appreciate. A lot of it has to do with being an artist who was encouraged to just try things. Dischord is a much more colorful and open sort of label than it has the reputation for.”

Unlike Jawbox or Shudder to Think, Smart Went Crazy never signed to a major label. And unlike Fugazi, they never ascended to legend status. But for the short time they played together, they capitalized on the white-hot burst of inspiration that kindled within them. Over time, the album has grown in estimation, influencing various other indie and punk acts, though at the time they were burning perhaps too bright. Clark credits their relative youth in the late ’90s, as well as the clash of personalities in the band, as reasons behind their inability to stay together. Less than a year after the release of Con Art, Smart Went Crazy officially disbanded, which Clark says, in hindsight, was “a relief,” however hard that might be to hear from fans of the band.

But Smart Went Crazy never got famous in their day, and given the intensity of the band, an early end was probably an inevitability.

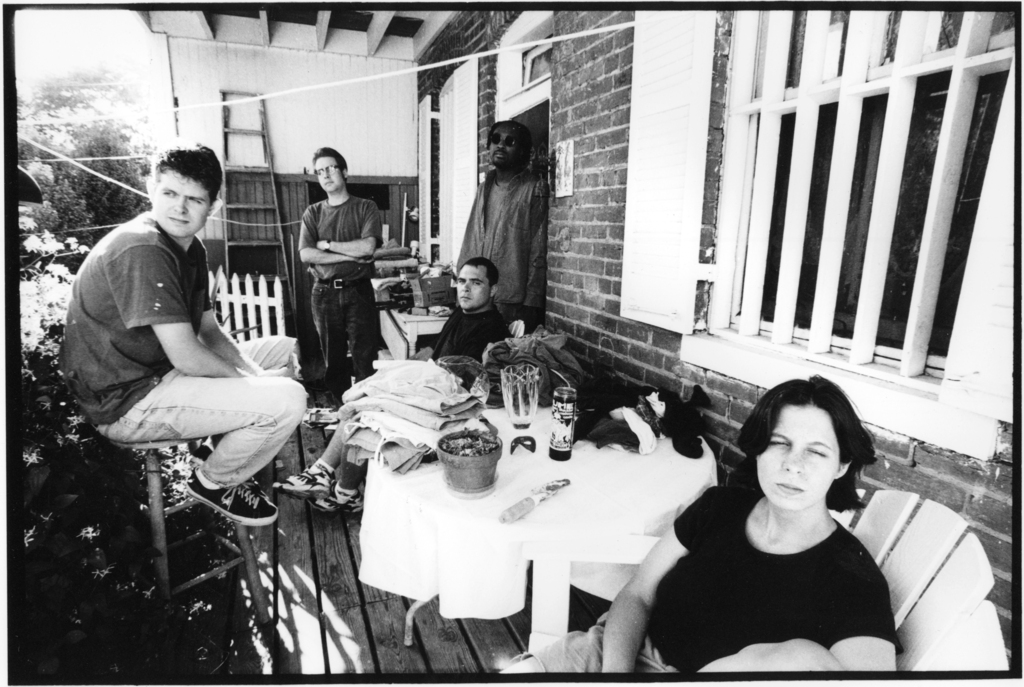

“I think the band had sensed that it might be our last record,” Clark says. “That was always a specter underneath the session, because it was a very intense group of people. It was a band I loved, but I was so relieved to end it. There were five intense, sort of emotional people and, I mean, if you’re ever in the room with that band, you could feel you were in the presence of some intense people. Everybody had strong ideas, and sort of conflicting ideas…so I think part of the ambition of that record was to sort of wring out all of the collective ideas of the band, from that one record, knowing that we would not make another one. We were an obscure band when we did that record. But the band has become more celebrated in its death than it was celebrated in its life, which is a little strange.”

In the years since Con Art‘s release, the various members of the band have been involved with a number of other projects. Drummer Devin Ocampo made the transition over to guitar and vocals in his later bands Faraquet and Medications. Guitarist Jeff Boswell also briefly joined Ocampo in Faraquet as the trio’s bassist. Meanwhile, Clark’s remained active with his own band Beauty Pill, though in 2007 he contracted a heart infection that required surgery to treat, and that kept him from being able to perform for a while, the next Beauty Pill record after that—Beauty Pill Describes Things As They Are—being released eight years later, in 2015.

Clark’s primary method of paying the bills is as a producer and engineer, however, his name appearing on nearly 200 albums in the past 20 years, including fellow D.C. acts The Dismemberment Plan, Q and Not U, Black Eyes and Mary Timony. He says that bands have actively sought out to work with him because of his time spent in Smart Went Crazy, giving credence to the idea that the legacy of the band is larger than the band itself ever was.

“Honestly, I’ve made more money from Con Art because it’s influential on other musicians than I have made from it in terms of royalties,” he says. “Con Art is highly regarded by musicians and sometimes they’re well known musicians, and that’s the way I’ve made my living since I made that record.”

Having just turned 20, Con Art was given its first proper reissue on vinyl by Ernest Jenning. Seeing as how Dischord didn’t have any kind of double-album template at the time, it’s a long overdue release, to be sure. But while Clark isn’t nostalgic to relive that era, he’s still pleased with the music that came out of it.

“I wrote liner notes for the reissue while we were in the remastering session,” he says. “As we were hearing those songs for first time in years, I remembered what it was like to make that record. There are some things about the record that are a little embarrassing, kind of like baby pictures, but I think it’s…a record that has come out of real passion, and I feel like it’s genuine. It’s not bullshit. I’m proud of having created something that feels genuine. That’s all I really want to do in my life. I still think it’s a cool record.”

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.