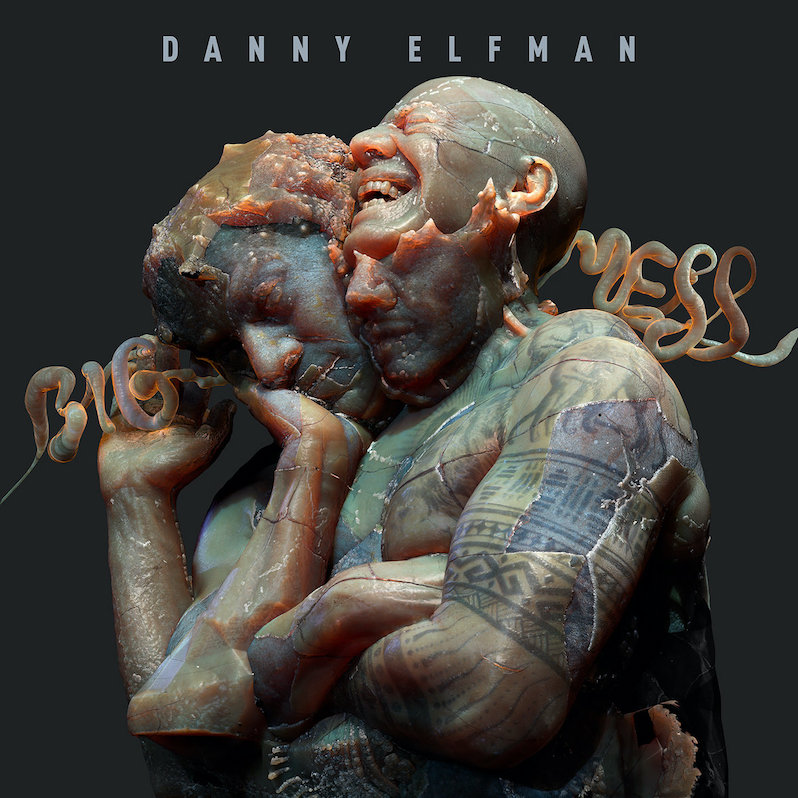

Danny Elfman : Big Mess

One would be forgiven, given the length of time between this record and his last of this style, to predict that things would be quite different for Danny Elfman in the context of rock. After all, it’s not just the time that weighs on all of our minds; those twenty seven years between 1994’s Boingo and this new release were not spent idly but instead marked by over 100 soundtrack projects, including the entire body of work of Tim Burton, several Batman films and The Simpsons. It would stand to reason that these decades of labor in one field and distance from another would make the resulting return a kind of amalgam of the two spaces, fusing approaches and arrangement notions pinched from the contemporary classical film score world and applying them within a rock context. Which is part of what makes it so intriguing that it doesn’t. Big Mess is fully and singularly a return to his previous sonic ideologies, a record which portrays itself as fascinatingly agnostic to all that came between this and the last of its kind.

In terms of legacy, Big Mess‘ attribution to Elfman alone doesn’t necessarily separate it from that of Oingo Boingo. Elfman was, after all, the sole songwriter of that previous group and, while the songs were clearly motivated in their shape in part by the players he surrounded himself with, Oingo Boingo was always less musically democratic than the similarly minded Mr. Bungle, a gestalt that radically changes shape as membership wavers. This new record does bear a single returning Boingo member aside from Elfman in Steve Bartek, former lead guitarist turned orchestration arranger, but aside from that the crew is wildly different from that of previous Boingo affairs. Despite this, the sonic idiom presented here picks up smoothly from Boingo, as effortless and time-erasing a return as nearly any we’ve experienced in rock music experimental or not. The wide-screen panoramic and cinematic flourish of late-era Boingo remains here, the world of film clearly lingering somewhat in the scope and scale of these arrangements compared to the nervy new wave/prog/ska hybrids of earlier material. The symphonic and at times AOR-adjacent approaches to mid-paced prog rock however have been altered based on notes from, of all places, the work of King Crimson, borrowing their uniquely angular post-industrial prog metal voice they developed in the 2000s.

This darkness is befitting where we previously saw Boingo. Songs like 1994’s “Insanity” and the dark and meticulous staging of their ’96 farewell live record/home video Farewell were clearly striving for where the material on Big Mess has landed. The fusion of industrialized punch and distorted blown out guitars and synth textures feels painfully natural, Elfman embracing the way his music with Boingo influenced the like of Nine Inch Nails and that wave of industrial rock that rose in the wake of his group as much as seemingly a sly confirmation of some connection between Elfman and the other progressive metal cinematic weirdo king Devin Townsend. These are experiments in name only; these approaches to experimental and progressive music are as well-vetted as they come, from the legends of King Crimson and Cardiacs to the smaller echoes of those bands practiced in microgenres dotting the landscape of prog. But the great beauty of music is that it is not validated or invalidated by being groundbreaking. Newness and novelty are benefits, certainly, but what matters at the end of the day is the quality of the songs and the assembled record as an aesthetic whole, not whether this is the first time a practice has been carried out. By that measure, Big Mess is once more unsurprising in its quality. Of course Danny Elfman would produce a compelling and synchronous whole.

This provides, ironically, a deep challenge in describing the record adequately. King Crimsonisms and industrial prog metal injections aside, what is there to say? Is it a surprise that the mastermind behind Oingo Boingo, one of the most venerated and influential of the new wave/prog fringe of experimental rock, would produce another record of quality? It’s origins speak to even Elfman being relieved in retrospect by its obviousness; the record began as two songs recorded before COVID for a then-upcoming festival appearance which was to feature Boingo material, medleys of soundtrack work and new material. When COVID cancelled the festival proper, Elfman simply kept the door open. Two songs became four, ten, then a full album. There were apparently brief attempts early on to carve it all down to a proper standard shape, attempts which were abandoned for the much broader and more engulfing final project we are presented. Both the rapidity of the creation of material and the seeming ease of the decision to keep the family together as it were shows perhaps the strongest influence of Elfman’s voluminous and prolific soundtrack work; these are pieces born from the same perspective and mindset, shards of the same mural, and their interlocking assembles a portrait that flows naturally from his pen to the vibration of the speakers. His decades spent flattening the distance between inspiration and creation are fully apparent here, both in its history and in the material itself. Big Mess is unsorted and nonteleological, like a modernist novel, no straight lines but instead the shrapnel of the hand grenade bursting. We don’t need to ask what the big mess is or ask how he replicates it formally in the music and structure of the record. It is apparent, instinctive, intuitive.

Still, as much as on paper it should not be a surprise that one of the most venerated heroes of this field and approach to rock music would create yet another great work in the field, it still kind of is, right? Like, writerly sentiments and prosaic structuralism aside, it is a miracle in a world where we have all learned we must be more consciously grateful for miracles as they occur. Big Mess isn’t just a good record; it’s one of the greatest of his career, conveying the ever-deepening sorrow and rage and joy and confusion Elfman was already so good at conveying, decades of life under neoliberal social collapse and generation after generation promising and then failing to save the world and set it all right leading to an obvious and reasonable profound well of pain. Big Mess is everything Boingo ever was, but darker now, richer now. All we can hope, as greedy as we are, is that the next one doesn’t take nearly as long. Maybe it took the world very nearly ending before his eyes for Elfman to rediscover the primalism that he once must have felt in the arms of rock and roll. Let us hope he is never given reason to forget or for the spell to be broken again.

Label: Anti-

Year: 2021

Similar Albums:

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.