With “Delia’s Gone,” Johnny Cash began a new act through an old tradition

By the time he was 60 years old, Johnny Cash had released more than 60 albums. He sang songs of love and outlaws, songs of faith and the Old West. He released a number of Christmas albums, a record of songs detailing the plight of indigenous peoples in America, and a spoken-word orchestral record about the Grand Canyon. Some of the albums that bear his name technically weren’t his choice to release—in the early 1960s after he was signed to his longtime label Columbia Records, Sun Records issued several odds-and-sods compilations of unreleased leftovers as a means of cashing in on his ascending popularity. Any way you measure it, though, Johnny Cash had pretty much done it all.

Cash also recorded an entire career’s worth of murder ballads. Just as often as he offered devout tributes to the almighty or professed tender expressions of love, Cash would look through the eyes of cold-blooded killers and men pushed to acts of desperation. Occasionally his outlaws would find more clever ways to take revenge on the society that beat them down, like the thief who pilfers a car the long way on “One Piece at a Time.” But more often than not they’d simply aim and pull the trigger—sometimes at a lover, occasionally a bystander, once even President James Garfield. His narrator famously shot a man in Reno just to watch him die, but he’s also accepted his fate to be executed so as not to dishonor the best friend whose wife he slept with, and took a bullet from a bigger, meaner cowboy who provoked him to draw his gun first. Cash in large part helped bridge the folk tradition of the murder ballad with contemporary popular music, and many of the best-known songs in the blood-stained songbook were either written or recorded by Cash himself. They were so much a part of his repertoire, in fact, that in 2000, Legacy released a box set called Love, God, Murder, in which an entire disc was dedicated to his songs of crime and punishment, bloodshed and revenge.

They’re also, unsurprisingly, some of Johnny Cash’s most beloved songs. Not so much because of the violence, though he never hesitated to walk into the shadows and touch the darkness firsthand. But rather because Cash is a master storyteller; his murder ballads don’t begin and end with the gunsmoke. They’re more like three-act plays where we see the motivation and consequences rather than simply the act itself, and it just so happens that love and God have a lot to do with these songs as well, taking the form of the spouses and family that grieve and the acceptance that comes with one’s final judgment.

By the 1980s and early ’90s, the outlaw types that Cash sang about were a trend of the past, usurped by soft-rock urban cowboy sounds and stadium-filling crossover stars like Garth Brooks. In his fourth decade of making music, Cash was still moving nearly at the pace he had been at his peak, but to diminishing returns. With disappointing record sales, Columbia eventually dropped him in 1986, and though he’d temporarily find a new label with Mercury, he had little success there either, despite pairing up with Paul McCartney on 1988’s “New Moon Over Jamaica.” All the while Cash had plans to build his own dedicated theater to be dubbed “Cash Country” in Branson, Missouri, universal retirement home for country musicians past their prime. As this was happening, Cash was also dealing with a number of health problems, having undergone surgery for his knee, heart and jaw. For that matter, Cash Country never ended up happening; investors pulled out of the multi-million-dollar project, dooming its prospects.

Which doesn’t necessarily mean Cash was headed toward retirement or even out of good ideas; in 1991 he collaborated with U2 on a surrealist, electronic future-country song called “The Wanderer” that would later appear on their 1993 album Zooropa as well as the Faraway, So Close soundtrack. (Also, weirdly, he contributed guest vocals to Christian punk band One Bad Pig’s cover of his own “Man In Black.”) But, at least based on how the industry saw Cash’s commercial performance, his career had slowed to a halt. After seeing Cash perform at Bob Dylan’s 50th birthday concert in 1992, Rick Rubin reached out to him with the prospect of releasing a new album of music on his label, American, to which Cash was initially skeptical, but curious. “He didn’t know who I was, but he wanted to understand why I would want to work with him because why would anyone want to work with him?” Rubin said. “I didn’t convince him. … I said, ‘Well, let’s just sit down and play me songs you love, and we’ll figure out what to do.’”

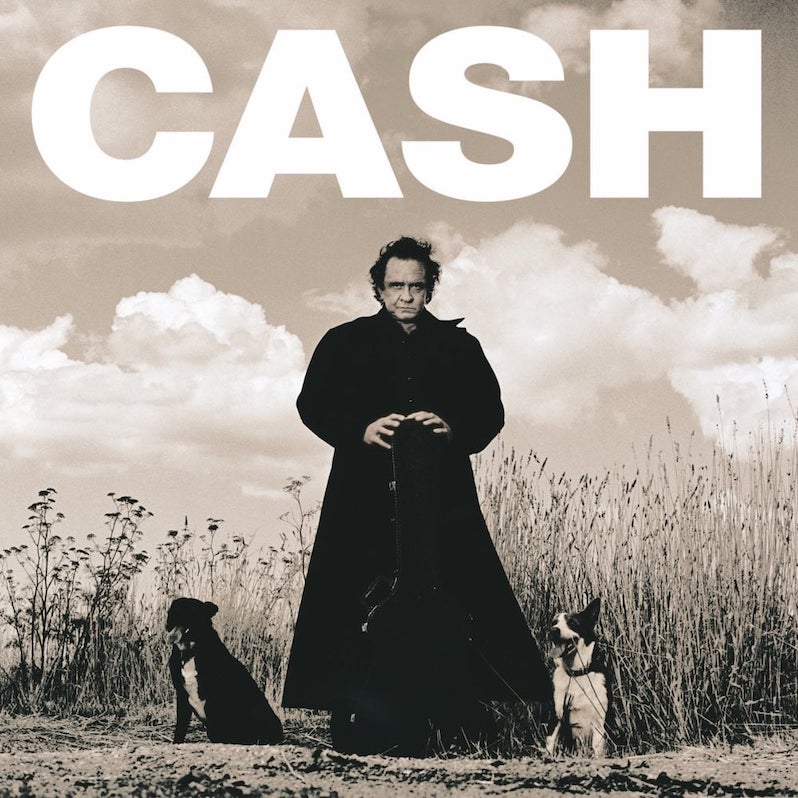

Recording a new batch of songs solo on acoustic guitar in his living room, Cash captured what would eventually be released as American Recordings, which revitalized the image of the Man in Black and earned him the most critical acclaim he’d received in decades. Though the sales still weren’t anywhere near his peak, with albums like I Walk the Line going gold and Live at Folsom Prison triple platinum, it nonetheless created demand for a veteran artist now in his sixties, reaching an audience who might have never heard him before. And though the album featured Cash playing songs written by the likes of Nick Lowe, Tom Waits and American labelmate Glenn Danzig, its first single wasn’t, like 1996’s “Rusty Cage” or 2002’s “Hurt,” a contemporary cover done in signature Cash style. It was, instead, a vintage murder ballad already familiar to him: “Delia’s Gone.”

Much like another well-worn Cash favorite with a victim suffering an untimely fate at the hands of his gun-wielding narrator, “Folsom Prison Blues,” he’d recorded “Delia’s Gone” more than once during his career. The first was in 1962 on his album The Sound of Johnny Cash, backed with a full-band arrangement that included two-thirds of his frequent collaborators The Tennessee Three. The version he recorded 32 years later is stark and simple, a reflection of the relaxed at-home sessions that produced his heralded comeback album. It’s at once more playful than the straightforward crime-and-punishment plucker from early on in his career and more haunting alike.

Part of that might come from the sound of hearing an aged Cash retell the story of a man driven to homicide in tones unobstructed by Nashville studio works. Its narrative is similar to a number of murder ballads that Cash had recorded throughout his career: Man shoots his wife twice, goes to jail and is eternally tormented by the sound of the woman he killed. But in this version, Cash also updates the lyrics to highlight not just the storyline but the rancor and malice behind the murder. The red-eyed, spite-filled narrator takes the extra step of tying his “low down and trifling” wife to a chair—the “kind of evil make me want to grab my sub-mo-sheen” he sings in the song’s most fucked-up, uncomfortably funny line. He still suffers the same fate, the same torment, but here it seems less like a crime of passion than a mission, planned and plotted. Delia’s death in 1962 might have been a shocking turn of events; her death in 1994 was an inevitability.

Remarkably, “Delia’s Gone” even received airtime on MTV, its bleak and gothic video depicting Cash burying the corpse of the woman he shot—portrayed by supermodel Kate Moss, no less. To say it was a hit would overstate the matter, but it did offer a reminder of the darkness that coursed through Cash’s music, the grit and black humor that might not have played in Branson.

Though there are numerous songs that Cash would record more than once throughout his career, “Delia’s Gone” is maybe the only one that’s actually in conversation with itself. They’re yin and yang, one a straightforward violence and retribution arc rendered in bright, Nashville studio tones; the other one is stark, mean and twistedly humorous. In much the same way that Cash helped update the murder ballad tradition for a contemporary country audience, he likewise carried on its tradition of continually updating and embellishing the story—even one he, himself, had told years before.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.