U2’s Zooropa was a product of limitless imagination

In the ’80s, U2 resisted the urge to give into the cliche of rock star excess, their earnest songwriting and passionate performances all they needed to sell the drama and awe of their consistently strong, stadium-engineered anthems. But eventually they had to face facts: They were rock stars. U2 sold millions of records, played in massive arenas and won Grammys. By 1993, bands didn’t get much bigger than U2, at least not without onstage pyrotechnics and wire harnesses and custom-designed backstage laminates, and thus it was decided—following the release of their weirdest album to date, 1991’s Achtung Baby—U2 officially embraced their status as outsized, leather-clad rock ‘n’ roll caricatures, and they’d push that stereotype to its farthest limits, eventually crossing over into terrain so weird that only a band this successful could convince their record label to finance.

U2 underwent a transformation with 1991’s Achtung Baby, a more radical embrace of industrial and electronic influences and art-rock maximalism, complete with a bit of a knowing smirk. They didn’t reach the final stage of that evolution until embarking on the ZOO TV tour, a 157-date, two-year trek across the globe that stands as the band’s most indulgent display. Surrounded by giant screens, the members of U2 were not so much a rock band as the cast of a massive multimedia performance art piece. They played songs, certainly, but more than that they put on a spectacle—DJs spinning records inside a painted Trabant, chopped-up video clips of George H.W. Bush appearing to recite the lyrics to Queen’s “We Will Rock You,” theater troupes wearing giant papier mâché heads resembling the members of U2, a second stage inspired by Elvis Presley’s ’68 Comeback special, bellydancers, ABBA semi-reunions and Salman Rushdie, for some reason. And of course the characters: The Fly, Mirror Ball Man and Mr. MacPhisto, the latter of whom made prank calls to The Pope and Alessandra Mussolini and tried to call himself a taxi onstage.

An undertaking as massive as ZOO TV is a creation unto itself, ostensibly something to serve the promotion of an existing album, 1991’s Achtung Baby, but the spectacle was something bigger than the album. It also stretched well past its press cycle—by the time the tour had gotten off the ground, the album was already out for several months, and by the time it had ended, more than two years had lapsed since its street date. To keep the momentum going, the band came up with the idea of releasing an EP—something short and simple—as a tie-in to the massive tour. What emerged from their studio sessions, instead, was the strangest studio album of their career: The weird and wonderful Zooropa.

Where Achtung Baby found U2 drawing inspiration from electronic and industrial music, Zooropa found them actually making that very music rather than implementing its textures in the service of a rock ‘n’ roll record. It’s an album that sounds unlike any other they had recorded, because the manner in which it was made is different than any other before it, both because it was the first to be built heavily from loops and samplers, and also because it was made in snatches of empty space during the group’s heavy tour schedule. Between long stretches of shows, they’d fly back to Dublin to do tracking for the album, stay late in the studio until 3 or 4 a.m., then fly back out the next day to pick up where they left off. Its frenzied electronic sound, by and large, was a reflection of the circus-like atmosphere they’d conjured on the tour stage. “[I]t turns out that your whole way of thinking, your whole body has been geared toward the madness of Zoo TV … so we decided to put the madness on a record,” Bono said in a 1993 interview.

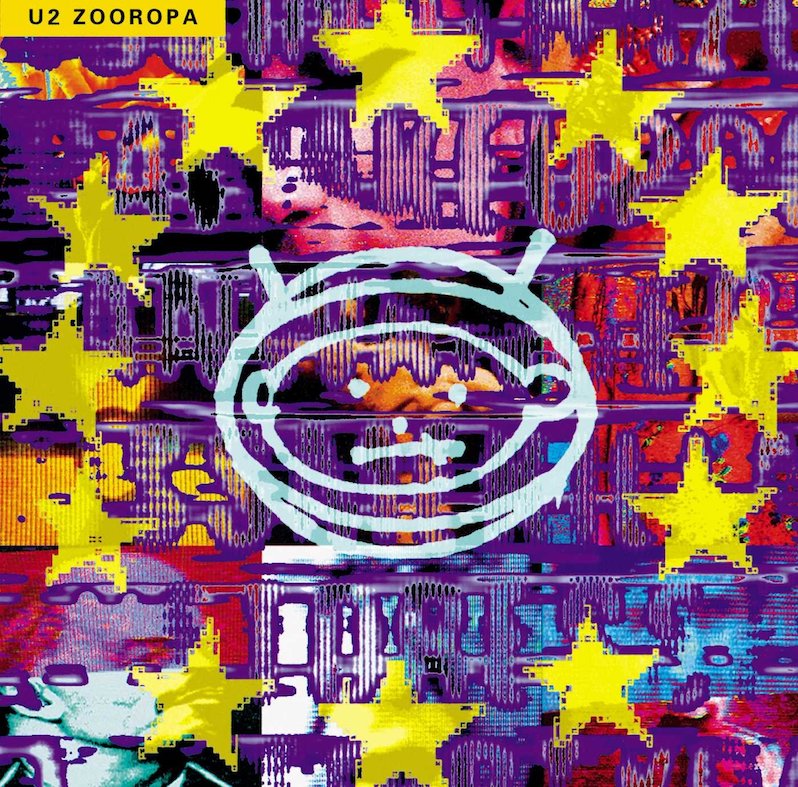

Zooropa is weird. Not just by U2 standards, but by the standards of pop music in general. Adorned with a kind of bizzaro-world image of the European flag (an animation of which also prominently played a role in the ZOO TV tour) and a crude cartoon image of a boy astronaut, Zooropa is to Europe what The Joshua Tree was to America. U2 had, for the most part, completely set aside the influence of American roots music in favor of the beats pulsing from Berlin clubs and the glitzy camp of ’90s Britain. Its most earnest moments come wrapped in tongue-in-cheek drama, its seemingly least serious harboring subtle political critiques. Like the best of U2’s albums, it seems to strive for a better world, but it guides the listener through an artificial neon playground on the search for utopia.

The oddball nature of the album and the band’s iconoclastic mindset at the time of the album’s making is evident in the first single “Numb,” a squealing industrial-dance thump defined by its layers of synths and loops and its monotone lyrical delivery from The Edge, and not Bono. If you heard this on the radio for the first time, you’d almost certainly need someone to tell you that it was U2, because outside of an innate tendency toward the hook, there’s nothing about this that feels essentially U2. Though it is a very cool song. There’s also a deeper subtext to it than advertised—deep within the mix is a drum sampled from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, a German propaganda film that the group included clips of on ZOO TV, juxtaposed against imagery of burning crosses and burning swastikas. At the time of the making of the album, they had grown particularly concerned about the spread of far-right nationalism throughout Europe and were making a statement about it decades before we saw just how deeply that rot had spread worldwide.

Its second single, “Lemon,” is a different story. Bono takes the reins back from The Edge, even though he spends most of the song singing in an affected falsetto. Still, you know it’s him, especially when he finds his emotional center and transitions into the earnest pre-chorus (“I feel like I’m slowly, slowly, slowly slipping under/I feel like I’m holding on to nothing“). Only it’s a disco song—more of a disco odyssey really, one that’s nothing but flash and spectacle in its opening verse but ultimately becomes a work of nuance and emotion, unquestionably one of the greatest, even subtlest songs in U2’s arsenal disguised as one of their most over the top.

The scope of Zooropa can be observed through the title track, which opens the record. It progresses in movements, the first a kind of muted, distorted trip-hop dreamscape littered with advertising slogans: “Be all that you can be,” “fly the friendly skies” and most notably, “Vorsprung durch technik,” an Audi advertising line that translates to “being ahead through technology,” a kind of mission statement for the album writ large. Yet halfway through the song it undergoes a metamorphosis, opening up into psychedelic ambiance before crashing down into a proper rock song, one still wallpapered with heart-on-sleeve slogans of U2’s own design: “Uncertainty can be a guiding light” and “She’s gonna dream out loud.” This kind of overbearing positivity would add unnecessary baggage to the band’s later records, but here it feels liberating: The future is whatever you want it to be.

In sound, Zooropa shares little in common with any other of the band’s albums, save for, in parts, its successor, 1997’s misunderstood Pop. Sometimes the album leans heavy on groove, like on “Some Days Are Better Than Others,” or dials up the cacophony, as on “Daddy’s Gonna Pay For Your Crashed Car,” which Bono described as an “industrial blues” song. But despite the many experiments that U2 undertake on Zooropa, it features at least one song that could have comfortably fit in on Achtung Baby: “Stay (Faraway So Close!)”. Written for the Wim Wenders film Faraway So Close!, a sequel to Wings of Desire that received mixed reviews, it’s a track that sheds the noise and the pulses and simply offers the kind of big-hearted anthem that listeners would have expected to hear. And, for that matter, it’s really good. Affecting but not overwrought, pretty but not ornate, it’s simply U2 being really good at writing a U2 song, and Bono once claimed it was the greatest they ever wrote.

Of all the least expected moves that U2 could have taken, though, recruiting Johnny Cash to sing lead vocals on closing track “The Wanderer” certainly felt, at the time, like the most radical. Up to that point, U2 didn’t really do guest stars, and they also didn’t write songs that sounded like Suicide played through digital sequencers. But “The Wanderer” somehow found them doing both, delivering what’s perhaps the least U2-sounding song in their entire catalog, and predicting Cash’s American Recordings comeback by a full year. (Rick Rubin must have been paying attention.) Cash narrates a landscape that sounds like the apocalypse: “I went out walking under an atomic sky/Where the ground won’t turn/And the rain it burns/Like the tears when I said goodbye.” But he could just as easily be talking about the desperate corners of America that the band visited on 1987’s The Joshua Tree.

The risk that U2 took with Zooropa didn’t pay off commercially in the same way that Achtung Baby did. It might sound strange to consider a platinum-certified album a disappointment, but coming off of an eight-million seller, it does feel a little like it came up short, especially since it was their lowest selling album since 1981’s October upon release. Bono, blessed with the gift for hyperbole, called it their Sgt. Pepper’s at the time, though he’s since rescinded that claim, and The Edge said the album was more of an “interlude” than a proper album statement, but he finds one of the most interesting moments in their catalog regardless. There’s a sense, or at least there was for much of the past few decades, that this was a “minor” U2 album, an experiment rather than a landmark. Which is true only if you choose to overlook the strength of its songs and the fact that an album this simultaneously left-field and maximalist could only come from a band at the peak of their powers. And they did it simply because they wanted to.

The best part of all this is that Zooropa wasn’t even the last of their ’90s-era experiments, nor the least commercial. For all its curious textures and aesthetics, Zooropa still had singles and hooks. But two years later, U2 regrouped with frequent collaborator Brian Eno under the name Passengers, crafting an album of abstract electronic music intended to soundtrack movies that don’t exist. Hence the title, Original Soundtracks 1. (There is no Original Soundtracks 2, though another one would certainly be welcome.) Original Soundtracks 1 isn’t a U2 album, even though it was made by U2—texturally, it’s more aligned with Eno’s solo ambient work, the rare exception being the space-age ballad “Miss Sarajevo,” which features a guest appearance from opera tenor Luciano Pavarotti.

Compared to Zooropa, Original Soundtracks 1 is meditative and serene, sometimes upbeat and urgent, but gorgeous throughout, from the shimmering ambient pop of “Your Blue Room” to the live-band IDM of “Always Forever Now” and the abstract ambient blur of “Ito Okashi.” It’s likely not an album U2 fans expected or even asked for in the ’90s, which makes its existence all the more interesting. It’s by far one of the prettiest albums the group ever recorded, as well as one of the most experimental. The stakes for it were low, almost nonexistent, which seems utterly bizarre for a band of this caliber. Much like Zooropa, they simply did it because they wanted to, whether or not it had any commercial viability (that they even left their name off the project suggested that its intent was to be evaluated and appreciated on terms separate from those of the band’s overall canon—which in hindsight seems naive, but understandable). It’s an artistic success if not a commercial one, standing the test of time on the merits of its possibilities rather than the weight of being a U2 album by any other name.

There’s never been a time when it didn’t feel as if U2 were swinging for the fences, but they’ve never outdone Zooropa and Original Soundtracks 1 in terms of sheer experimental freedom. There’s an irony in considering either of these minor U2 albums, because that’s ultimately a perception of marketing. As far as ideas go, it’s hard to imagine a time when their imagination seemed so limitless. They were dreaming out loud.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.

Superb article – really enjoyable and thought provoking read – thank you.

Beautiful and so personally written and researched.

Great article. Very thoughtful. Zooropa is one of my favorite albums by U2. I wish they would do more experimental music.