Oasis’ Be Here Now was indulgent, but overflowing with vivacity

Do you remember Oasis in their heyday? Personally, I don’t, although that’s largely because I was born in 1996. It was an important year for us both, actually; while I first arrived into the world, Oasis were on top of it. That year saw their historic gig at Knebworth, performing in front of upwards of 100,000 fans. But, in many fans’ eyes, it was also the point by which the band’s best work was behind them.

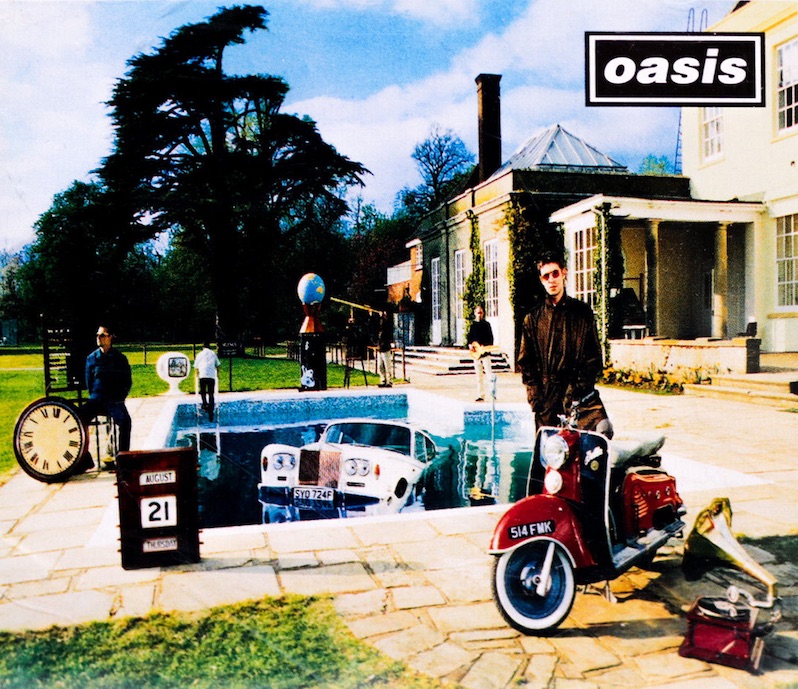

Those fans, I believe, are wrong. Because one year later, Oasis released their third and arguably best studio album, Be Here Now. And make no mistake: Be Here Now has engendered plenty of argument.

At the time of its release, it was the fastest-selling album in the UK ever, and by 2016 had sold 8 million copies worldwide. Its detractors are similarly substantial. Critic Jon Savage claimed the release of Be Here Now, and its failure to live up to the frenzied hype generated by Oasis’ first two records, was the event that killed Britpop (an alternate theory to the one that Pulp’s This Is Hardcore was the culprit). Twenty-five years later, the fan response has mellowed out into a general acceptance that, though the album does contain flashes of the vital Oasis synergy that fundamentally shaped the ’90s, it’s often dulled by such a grandiose swelling of cocaine-fueled excess that it’s rare for its quality to rise above decent, and all-too-common for it to stray into mediocre. Which is an assessment a darn sight better than the one offered by one Noel Gallagher, who has described the album as simply “fucking shit.”

Be Here Now elicits this mix of reactions partly because, if any other album in history contains a more brazen marriage between sheer optimism and extraordinary pretentiousness, it has not yet been written. Perhaps it can’t be. After all, a common criticism of Be Here Now is that the whole thing reeks of over-indulgence. That’s a fair cop. The album is exceptionally long, with all songs but one running over five minutes, and the vast majority landing somewhere around the six- or seven-minute mark. Every song is crammed full of twirling fills and riffs that suggest little artistic discretion and a grand conviction that everything being written is pure musical genius that the masses cannot be deprived of.

But for all Noel Gallagher’s tiresome present-day whinging about how Oasis were the biggest band ever, the fact is that, once upon a time, that might have been close to the truth. All things must be considered in context: Oasis’ context is that they were a group of young working-class men living in a part of the country that had spent the previous decade being ravaged by Thatcherism, and they were suddenly being propelled toward unimaginable fame and fortune. If you came from humble beginnings and found your words, your voice, your style, and your music had turned you into a critical darling and multi-millionaire, then wouldn’t you be a little cocky as well?

“D’You Know What I Mean?”, the album’s opener, embodies this kind of swagger, and seems a conscious nod to the ambiguous lyricism that’s been an Oasis mainstay since time immemorial—the hook in “Some Might Say”, “The sink is full of fishes / She’s got dirty dishes on the brain,” for instance, or the famously nonsensical “Slowly walking down the hall / Faster than a cannonball” from

“Champagne Supernova.” Such lyrics had been attacked by critics, who held that their meaninglessness prevented the songs from becoming hits. But—who knew?—those critics were wrong.

“D’You know what I mean?” It turned out they did. They knew, to the tune of 2.5 million ticket applications for Knebworth—that’s more than 4 percent of the entire population of Britain. They knew, to the extent that an estimated one in every three UK homes in the mid-’90s owned a copy of What’s the Story (Morning Glory)? Oasis are certainly bragging, but you can’t say they’ve got nothing to brag about.

Once you understand the source of the album’s palpable braggadocio (besides, you know, the cocaine), then you’ll see that the vivacity the album overflows with is joyful, harmless, and deeply alluring. The songs are long, sure, but that’s because the band are inviting you to get lost in them—to stretch out that explosion of euphoria and live inside it for as long as you possibly can. And most tracks really do use their runtime effectively, building up to a tremendous, victorious climax whose triumphant brass sections and exuberant, white-hot solos will sail you up into rock ‘n’ roll heaven if only you don’t take yourself too seriously to let it.

The intoxicating happiness of tunes like “It’s Gettin’ Better (Man!!),” “The Girl In The Dirty Shirt” or even “Magic Pie” play like Oasis have opened a musical space to be filled to the brim with as much jubilation as their instruments can handle. The fuzzy, cacophonous roar of the guitar is the sound of music bursting at the seams, boasting an energy that can barely be contained. As for the name itself, Be Here Now might well be the most direct expression of hedonism ever to grace the English language. It is a title that demands you bring yourself to the experience in your totality, and in return, you can be sure that Oasis are bringing all of themselves, too (so much so that they couldn’t even fit themselves in if not for the famous reprise at the end).

Despite its flaws, this record works so well because it remains at heart so endearingly and relentlessly joyful. Be Here Now is not complicated. Its emotions aren’t intricate or convoluted. They’re just enormous. There are no frills, no tricks, and absolutely no attention paid to anything except a straight-forward good time. And in 1997, Oasis wanted to share that with us. Aren’t we lucky?

***

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.