The aging, hipster name-dropping narrator in LCD Soundsystem’s 2002 debut single “Losing My Edge” mentions 56 bands in his cred-thirsty screed. He has every song by The Beach Boys and takes credit for introducing Daft Punk to the rock kids. He mentions Niagra and Pere Ubu twice, says “The Sonics” four times in a row, and puts an exclamation point behind each of Gil Scott-Heron’s names. He covers no wave, boogaloo, spiritual jazz, hip-hop, psychedelia and reggae.

But the first band he mentions is Can.

That’s because there’s no band cooler than Can. I could go into how radical their take on rock music was when they debuted in the late ’60s. Or I could discuss how immeasurable their influence is, more than 50 years after the fact. And I will. But that ineffable sense of cool defines them just as much as their psychedelic improvisations, their dismantling and reconfiguring of rock ‘n’ roll tropes, and their hypnotic rhythmic pulse. They find an impossible intersection of esoteric and accessible, unpredictable and in a groove, effortless and virtuosic.

Cool isn’t something you can put a specific value on, not by any meaningful measurement anyhow. It’s more instinctive, an I-know-it-when-I-see-it kind of thing. Cool can be acquired, but it can’t be taught—and you can lose it just as easily as you gain it. But Can, whether at their weirdest or most accessible, seemed to have a limitless supply, as if channeled from the ether.

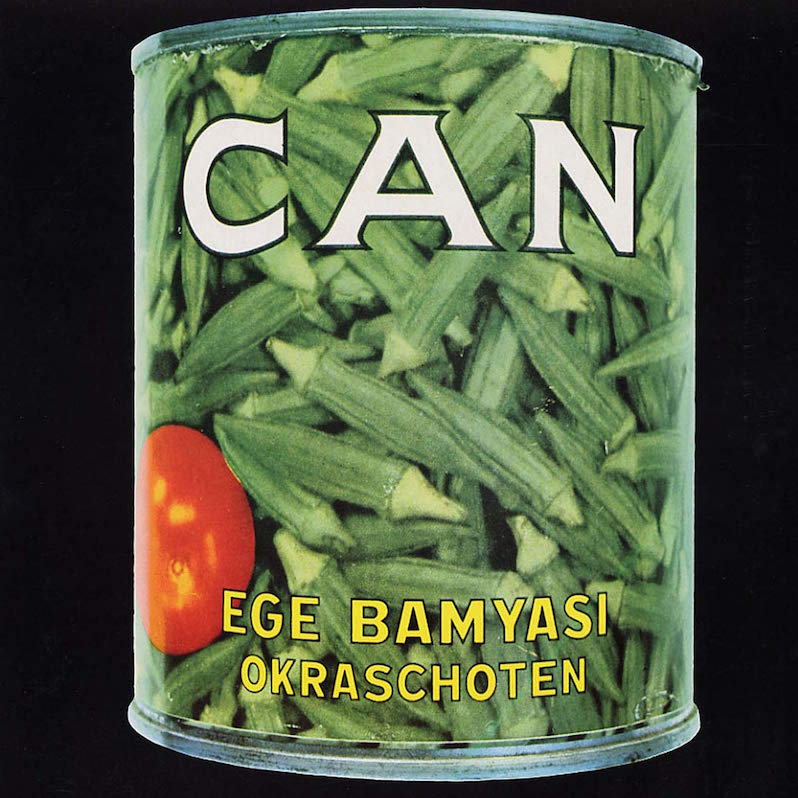

It’s unmistakable when listening to the group’s fourth album Ege Bamyasi, as concise and as complete a statement of Can’s aesthetic as the group ever released, harnessing a preternatural groove for something that feels more approachable and at times even more emotional than anything they’d released prior. It’s often characterized as one of the band’s darker albums, and its sessions were fraught with setbacks, among them Michael Karoli’s hospitalization for treatment of an ulcer in addition to obsessive, marathon-length chess matches between Irmin Schmidt and Damo Suzuki that pushed them ever closer to deadline. In spite of these complications, or maybe because of them, they emerged with a record that captures the essence of Can in the most digestible package.

A German band whose approach was born of avant garde influences, many of them American, Can’s beginnings in the mid-1960s stem less from bashing away in a garage than in the world of modern classical composition. Keyboardist Schmidt spoke of being “corrupted” by his time spent with artists such as La Monte Young and Terry Riley, and he and bassist Holger Czukay both studied with fellow Cologne artist Karlheinz Stockhausen. Drummer Jaki Liebezeit, previously a musician in free-jazz ensembles, had grown bored of that world, while guitarist and Beatles fan Karoli, the youngest of the group by a decade, brought the most overt rock influence to the group.

That curious mixture of abstract, outré sounds and the new rock vanguard was neither entirely unprecedented nor accidental; The Velvet Underground had, arguably, built something of similar hybrids but different ratios a few years earlier. But Can’s approach didn’t sound much like their American counterparts—theirs felt fluid and loose, with more movement in the back end, while drone and boogie seemed to be extensions of one another rather than working in opposition.

That stylistic makeup yielded a loose and hypnotic proof of concept with 1969’s Monster Movie, the only full-length album recorded with their first vocalist, American Malcolm Mooney, before he moved back to the U.S. for the benefit of his mental health. The loose ends of the next year’s Soundtracks bridged the gap between Mooney’s departure and the proper full-length debut of Can’s second vocalist, Suzuki, a Japanese-born busker whose presence on 1971’s double-length masterwork Tago Mago brought an added sense of spontaneity and dynamism to an already impressive musical force.

By 1972, the momentum that Can had built up found them as creatively unencumbered as ever, but they employed more creative use of editing, much in the same way that Miles Davis had been just a few years prior with his fusion breakthroughs like In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. And where their previous album had been recorded in a castle, its 70-plus-minute sprawl befitting the grandeur of its locale, the group captured Ege Bamyasi inside of a repurposed movie theater they called Inner Space, which also ended up being Czukay’s home, soundproofed with reclaimed military mattresses. The middle piece of their triptych with Suzuki—a triad of masterpieces recorded during his brief but incredible three years with the band that closes with the bright and pristine Future Days—Ege Bamyasi is the greatest document of Can’s most stunningly creative era, made all the more satisfying by emphasizing immediacy as much as improvisation and experimentation.

To the extent that Can has any hits—perhaps a matter of perspective, though one of them would inarguably be 1976’s “I Want More”—several of them can be found on Ege Bamyasi. More specifically, it features their biggest actual hit, “Spoon,” which cracked the German top 10 chart and sold 300,000 copies in their home country, thanks in large part to its use as the theme song for the TV show Das Messer, tying in thematically with their set of music for films released on 1970’s Soundtracks, but an even stronger representation of their strengths, compressed into a piece that fits on a single side of a 7-inch.

“Spoon” may or may not be Can’s single greatest song, if I’m not overthinking it—though once I do, I have to acknowledge “Halleluwah,” “Yoo Doo Right” and “Bel Air,” their triptych of monoliths. In miniature, though, it’s the very ideal of the band’s cosmic art rock, looping and swirling, ascending into a glorious chorus. Though by no means their first real pop song, it’s the one that best employs their repetition and penchant for judiciously employed bells and whistles, an early precursor to indie omnivores like Stereolab. It’s also, naturally, the song from which Spoon took their name, as well as the name of the label eventually launched by the band.

Then again there’s “Vitamin C,” arguably the funkiest song ever made by a German band (yes, yes, “Halleluwah” again, duly noted). The rubbery interplay between Liebezeit’s beat and Czukay’s bassline form something deeply physical and compulsory, the most dance-oriented that the group had ever sounded at that time, and a song that, 50 years after the fact, hasn’t lost any of its thrill factor. Someone once brought me a beer on the spot when I dropped it into a DJ set, and I vow, under similar circumstances, to pay that good deed forward.

The groove never really lets up on Ege Bamyasi. The band seems to literally drop you into the middle of it on leadoff track “Pinch,” one of their songs that carries the sonic vibe rather than the modern editing techniques of ’70s-era Miles Davis, in addition to being one of the album’s longest pieces. And amid its deep-pocket rhythms and wah-wah scratch, they allow in a bit of levity by way of a slide whistle. “I’m So Green” is similarly frenetic but not nearly as heavy; though The Stone Roses claimed to not have been heavily influenced by Can, even bassist Mani couldn’t deny the similarities between this song and their own “Fool’s Gold,” recorded 17 years later.

The songs that step into even stranger realms still retain their hypnotic appeal, funk or no funk, like the eerie psychedelic waltz of “Sing Swan Song,” a song that approximates “Venus in Furs” with melted butter coating its harshest edges and its tonal and structural sketches remain visible in ’90s-era Radiohead. Or “One More Night,” a fascinating piece of proto-electronica that, while not quite as shiny and pristine as their contemporaries in Kraftwerk, sounds immaculate beneath a discoball all the same. And “Soup,” Czukay’s favorite from the album, is the weirdest, wildest and longest song of the batch, disintegrates in a haze of effects and Suzuki’s strangest incantations.

Fifty years since its release, Ege Bamyasi is less of a closely held secret than when it was released, its highlights showing up in Netflix original series, indie flicks and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice, and covered by the likes of Beck and Stephen Malkmus. In 1972, rock ‘n’ roll was a lot younger, by some measure sufficiently peculiar, but still with a lot weirder to get. Can helped accelerate the process, all too eager to step out of arbitrarily drawn bounds in their aim to find the place where popular and provocative meet.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.