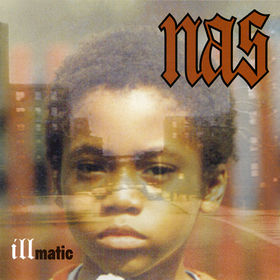

Kendrick Lamar : good kid, m.A.A.d. city

“Real” is a loaded term in hip-hop. For years its meaning has been manipulated to denote any hip-hop album or artist to follow the letter of the Backpacker Conventions. It’s one-syllable sanctimony, and a condescending dismissal of any aesthetic or experience that doesn’t meet some arbitrary measure of value in rap music. But even brushing aside the inherent absurdity of determining what’s considered “real,” even that which seemingly fits the rap snob’s definition of hip-hop is pretty contradictory. Q-Tip produced tracks for the notoriously menacing Mobb Deep. Lupe Fiasco went pop rap about two albums ago. And a flip of the coin will tell you which side Common falls on this week.

“Real” is also the title of the penultimate track on Kendrick Lamar‘s new album, good kid, m.A.A.d city, and its hook is pretty straightforward: “I’m real/ I’m real/ I’m really, really real.” This doesn’t mean he’s trying to resurrect Rawkus or Native Tongues or anything—getting a handle on Lamar’s approach or aesthetic takes more understanding of nuance than that. No, he means it literally: He’s telling the story that only he can tell, because it comes straight from his own experience. It’s not needlessly moralizing, nor cartoonishly frivolous. It’s, quite simply, real.

For Kendrick Lamar, however, real doesn’t equate to drab or understated. On his major label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d. city, his intricately detailed autobiographical account of his own experience growing up in Compton finds him caught between faith, family and a gang lifestyle that’s continually on the precipice of pulling him in. Yeah, it’s a little heavy; the album even begins with a prayer. But the seriousness and weight that Lamar stuffs into his narrative never overwhelms the accessibility or enjoyability of the material, and moreover allows for more humor and levity than it lets on. He’s a dynamite rapper, for one, changing his flow on a track-by-track basis not merely for the sake of packing in quotables like sardines (which he does), but to heighten the drama, or as the case may be, the almost caricaturish bravado of his less mature self. On “Backseat Freestyle,” for instance, K-Dot boldly claims he “pray my dick get big as the Eiffel Tower/ so I can fuck the world 72 hours.“

Subtitled “A Short Film by Kendrick Lamar,” good kid, m.A.A.d. city runs a pretty hefty 68 minutes and follows a linear storyline that begins with a spotlight on Kendrick at 17, borrowing his mom’s van to meet up with a girl named Sherane. Lamar pretty effortlessly replicates perspective of a horny young male with “nothing but pussy stuck on my mental,” spending his verses going over the potential scenario in his mind, almost getting into a fenderbender and finally hearing his phone ring as “two n*ggas, two black hoodies” approach, ominously foreshadowing some darker days ahead.

From “Sherane” on forward, Kendrick takes the listener through various checkpoints on his road to adulthood, and punctuates them with eye-popping sequences of lyrical dazzle, as well as the occasional appearance of a voice mail from a loved one, providing the conscience and structure that brings him back down to earth even when a situation goes bad, as on “The Art of Peer Pressure.” One moment of bad judgment (“I got the blunt in my mouth/usually I’m drug free, but shit, I’m with the homies“) spirals into a moment of really bad judgment (“Rush a n*gga quick and then we laugh about it/ That’s ironic because I never been violent, until I’m with the homies“). Elsewhere, Lamar highlights his own ripening as a rapper, his non-stop flood of teenage boasts and one-liners on “Backseat Freestyle” preceded by a friend playing a beats CD in his car. He falls prey to racial profiling by the police in “good kid,” spits a stressed, frayed and frazzled vendetta from being pushed to the edge by gang violence in “m.A.A.d. city,” and on “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst,” fixates on his own mortality, outdoing Bob Fosse’s own surreal metafiction in All That Jazz by writing his own death twice.

Kendrick’s linear memoir-style narrative glues the album’s 12 individual tracks, with some assist from the interludes that dramatize interactions with friends and messages from relatives. But for an album that features a different producer on almost every track, it maintains a cohesion that rivals even the work of a more hands-on Renaissance artist like Kanye West. In fact, the production on the album is uniformly outstanding, displaying lush jazz samples on “Sing About Me” and “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” courtesy of Like and Sounwave, respectively, while descending into a dark, nihilistic atmosphere in “Swimming Pools (Drank)“, mirroring Lamar’s own battle with his conscience over his self-destructive behavior. But in the laid-back, hypnotic atmosphere of “Real,” his mom gives him a little perspective and a lot of hope — “If I don’t hear from you, by tomorrow… I hope you come back, and learn from your mistakes. Come back a man…”

In the final track, “Compton,” however, all the doom, gloom and personal struggle that’s been haunting Lamar fades away on a party track that celebrates the town on which the album centers, with none other than Dr. Dre joining the celebration. It feels more like an encore than a proper closer, but it serves an important purpose in the album’s progression. Kendrick goes through so many trials and tribulations (and death(s)) that it’s only natural to celebrate his arrival at this point with a big, commercial exclamation point. As it all comes to a close, we hear young Kendrick asking to borrow his mom’s van. It comes full circle — the story of a kid coming to his own in a harsh environment, told as an epic hip-hop saga, with the protagonist coming out the other end older, wiser and stronger. It’s stylized, and maybe even embellished, but it’s a story of redemption that’s not only compelling, but real.

Label: Top Dawg

Year: 2012

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

Similar Albums:

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.