Savages : Silence Yourself

In the 1970s, when bands in the U.S. and the UK began to wrench and twist the aesthetic of punk into newly abstract shapes and experimental forms, the definition of “post-punk” was born anew with each artistic permutation. In the hands of a provocateur such as Siouxsie Sioux, it was brash and confrontational. When forged by the likes of Joy Division, it took a darkly introspective turn. It could be political (Gang of Four) or satirical (XTC) or absurd (The Fall). While the similarities between any of these bands might be tenuous, beyond scratchy guitars or an often dark ambience, the pursuit of artistic ideas outside of a familiar norm, sometimes dangerously so, served as the glue that tied them together.

When a post-punk revival of sorts emerged in the early ’00s, however, it was mostly just stylish. It made sense for its time and place—by the time the grunge and nu-metal born of the 1990s had hit an aesthetic nadir by the early ’00s, a band of brooding sartorialists like Interpol were necessary to absolve the sins of the previous decade. That they released a debut album as strong as Turn On the Bright Lights made the case even stronger. Over time, however, the solution grew increasingly diluted. Interpol begat Stellastarr*. Stellastarr* begat Editors. Editors begat She Wants Revenge. And ultimately all that was left in post-punk was style itself—no confrontation, no experimentation, and especially no danger. But it doesn’t have to be that way, not if Savages have anything to say about it.

London’s Savages practically emanate danger from their pores. There’s an intensity about their songs that’s perpetually on the edge of teetering into chaos or outright menace, and it occasionally does. On their Matador Records debut, Silence Yourself, the instances in which the band ratchets up the adrenaline far outnumber those in which they court mainstream accessibility or radio friendliness. All of the songs are strongly melodic, many of them catchy, yet they don’t so much “catch” as clutch or throttle, and then sink their venomous fangs.

The visceral unease that Savages create is largely a result of the amount of noise they make, which is a pretty hefty amount. In aesthetic, the band might veer closer to the melodic darkness of Joy Division or The Sound, but there’s a snarling beast in their songwriting that descends from the likes of Swans or This Heat. Guitarist Gemma Thompson chugs out some deadly fierce riffs, from the dizzying churn during the chorus of “No Face” to the “Holiday In Cambodia” fretboard descent on “Husbands.” But Thompson has good company; bassist Ayşe Hassan holds down a perpetually ominous low end, sometimes with serpentine groove (as she does on “Shut Up”), while Fay Milton sometimes beats her drumkit with punishing ferocity, doling out frightening wreckage on her cymbals. To say Savages have chops would be an understatement. They’re laser-focused and precise—violently so.

When accompanying a ferocious frontwoman like Jehnny Beth, however, music as powerful as Savages’ is an absolute necessity. She’s alternately thrilling and intimidating as a singer, a descendant of Siouxsie Sioux in presence and theatricality, and a successor to a socio-political provocateur like Gang of Four’s Jon King. Yet there’s a personal and deeply intimate quality to Beth’s lyrics and observations, expressions that dig much deeper than braying slogans or wearing a Ché Guevara t-shirt. She puts a spotlight on the vulnerability of convictions on “Shut Up,” declaring, “I’m the one who truly saw your soul,” with the almost threatening caveat, “If you tell me to shut it, I’ll shut it now.” Her reading of the title of “I Am Here” is one of her most dazzling moments, not merely a declaration of corporeal presence, but a demand of recognition. Tackling sexuality, Beth can seem alternately tender and predatory. As abrasive as “City’s Full” is, there’s a moment of touching realism, with Beth admiring “the stretch marks on your thighs” and “the wrinkles around your eyes.” Yet “She Will” has a much more sinister take on sex, with a protagonist who will “kiss like a man” and “get hooked on loving hard/forcing the slut out.”

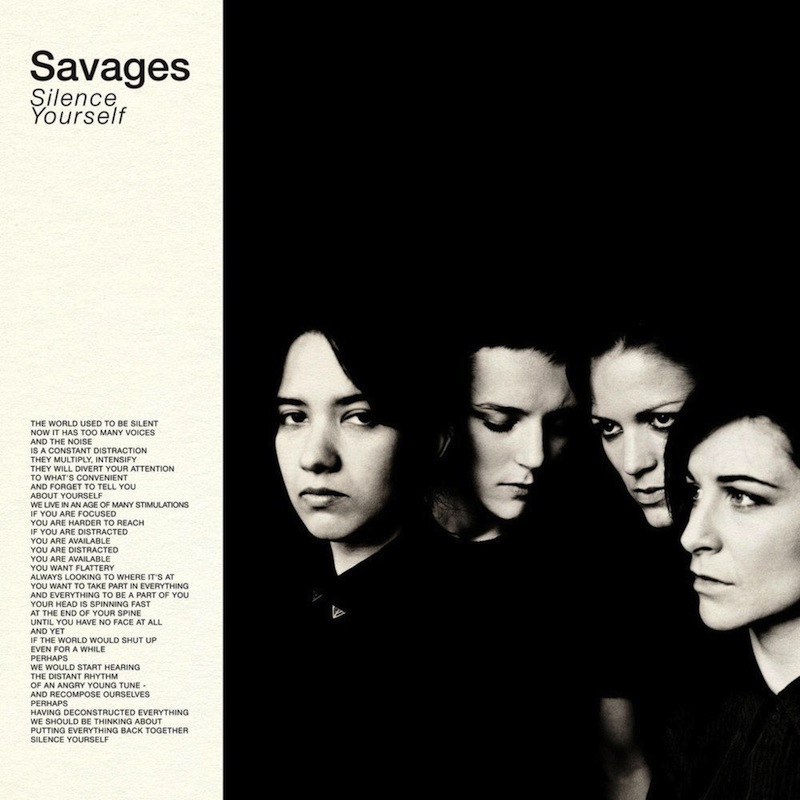

Printed on the front cover of Silence Yourself (which, legibility-wise works best on vinyl) is a poem-cum-manifesto that states “The world used to be silent, now it has too many voices” and “if you are focused, you are harder to reach.” And the title, Silence Yourself, gets at a recognizable if uncontrollable truth, being that the truth itself is too often lost when there is too much being said to actually be processed. Savages are certainly immune to the same problems every band is — capturing the attention of an audience shackled to mobile devices, for instance—but they also have a pretty powerful weapon against them. Savages’ is a post-punk sound powerful and lethal enough to cut through the voices and silence the noise; from the moment Silence Yourself begins, nothing else in the world seems to exist.

Similar Albums:

Iceage – You’re Nothing

Iceage – You’re Nothing

Joy Division – Unknown Pleasures

Joy Division – Unknown Pleasures

PJ Harvey – Rid of Me

PJ Harvey – Rid of Me

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.