Celebrate the Catalog : Sleater-Kinney

This article was originally published in 2015 and has been updated in 2021.

Excerpts of this article were taken from a rejected 33 1/3 proposal.

—

“Sleater-Kinney’s aesthetic is not to get up there and be sloppy and go, ‘Whoops, we don’t know how to play.’ We do know how to play.” – Carrie Brownstein, Spin, May 1997

A product of the first-wave riot grrrl movement in Olympia, Washington, Sleater-Kinney grew from the same kind of do-it-yourself spirit that characterized punk rock’s earliest days. But on a musical level, Sleater-Kinney were doing something that not just anyone could do.

On stage, Sleater-Kinney showcased a kind of magnetism and charisma that rarely surfaced in indie rock circles. Plenty of American bands in the ‘90s suffered from either terminal aloofness or a complete unwillingness to actually, y’know, move, yet the three women of Sleater-Kinney brought to their live show an explosive energy more typical of musicians whose names alone could fill stadiums. Tucker’s manic vocals, arresting enough as they were on record, sounded positively superhuman when experienced up close. Carrie Brownstein, a consummate performer, rocked her axe with dazzling theatricality; Pete Townshend-style windmills were almost always a key part of her repertoire. And Janet Weiss maintained a contrast between primal aggression and grace behind the drums, her neatly trimmed bangs blowing in the breeze provided by a small electric fan she kept next to her kit. And amid all the breathless vocal performances and chaotic punk rock storms, Corin Tucker, Brownstein and Weiss pretty much always looked like they were having the time of their lives.

This can’t be emphasized enough. Professionalism, practice and a relentless dedication to perfection can make a band tight, even flawless. With Sleater-Kinney, however, there was something much more. There’s a chemistry that studio rehearsals, alone, can’t create; the synergy between these three women is something that can’t be taught. Watching the band, one truly got the sense that they performed and recorded together for so many years because they truly wanted to. They never succumbed to egotistical flame-outs, eschewed the kind of interpersonal drama that destroyed hundreds of other bands, and saved all of their intensity for the studio and the stage, which is where it mattered most.

Now three albums deep into a second act, it seemed like the right time to revisit the music that made the band unique — extraordinary, even. We hope that you, in turn, will make your own dive into every Sleater-Kinney album. It’s a journey well worth taking.

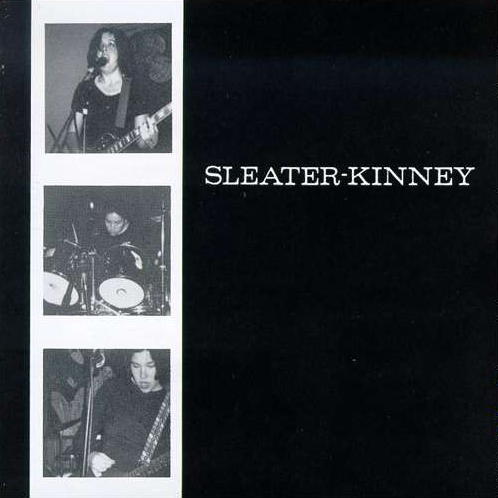

Sleater-Kinney

Sleater-Kinney

(1995; Chainsaw)

Sleater-Kinney began ostensibly as part of the “riot grrrl” movement in the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s, their earliest songs blending the feminist politics of bands like Bikini Kill with a uniquely artful take on melody that set them apart early on. And there is an early glimmer on Sleater-Kinney’s self-titled debut of what they would soon become, though it wasn’t the same band—not exactly, anyway. Recorded with first drummer Laura McFarlane, the album doesn’t have the same rhythmic intensity as those recorded with longtime drummer Janet Weiss. It would be a couple years until she would become the group’s Keith Moon and John Bonham (sans wrecked hotel rooms), but this is at least a good indication of how much talent the group was packing, even at their most raw.

Now, Sleater-Kinney often tried to distance themselves from being weighed down by the “riot grrrl” tag—which pretty much didn’t even apply within two years—but here, it’s about as close as they came. Sleater-Kinney touches upon topics like rape and sexism on tracks like “How to Play Dead” and “A Real Man,” respectively, and Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein attempt a sing-speak-scream cadence closer to Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna than on any of their other albums. But Sleater-Kinney evolved quickly and impressively, as we’d find out just one year later.

Rating: 7.0 out of 10

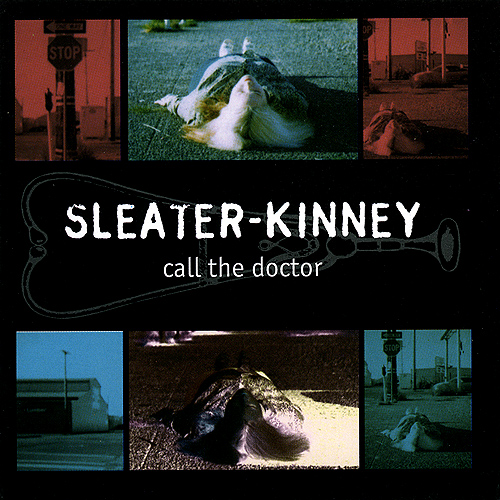

Call the Doctor

Call the Doctor

(1996; Chainsaw)

Call the Doctor, Sleater-Kinney’s second album, is cut from a similar cloth as that of its self-titled predecessor. It’s loud, raw and sinewy, for starters, and for all intents and purposes, a punk record with some post-punk and progressive elements. It’s hard not to hear it as the band’s most abrasive record either; just listen to those distorted screams near the end of the title track. That’s some pretty gnarly stuff right there. And “Little Mouth” is nothing if not utterly visceral; I’m pretty sure the actual feeling the band was going for was a punch right in the stomach. And they make that sucker count.

But Tucker and Brownstein are also writing much stronger melodies here; “Good Things” is almost a ballad, and a highly affecting one at that, even if it still sounds a lot like a punk song. “Stay Where You Are” has one of the most immediately infectious choruses of the bunch. And “I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone” is the band’s first real classic anthem, and a bit of insight into their personalities beyond the musical persona they put forth. One of the things that always struck me about Sleater-Kinney was how much they carried themselves as fans rather than insiders. You can see Sabbath posters on their album covers, and they’d tell stories about meeting Robert Plant onstage. Using Joey Ramone as the ideal for a hero seems perfectly in character, and a reminder that, ultimately, Sleater-Kinney are coming from the same place as their listeners.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

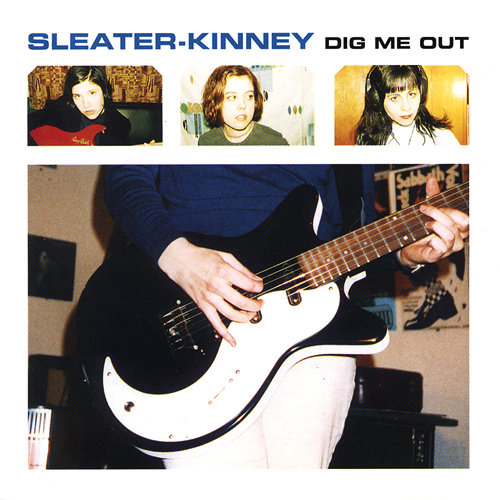

Dig Me Out

Dig Me Out

(1997; Kill Rock Stars)

After McFarlane left the band, all it took was one rock-solid audition from Janet Weiss in Tucker’s basement, and a few months later they would emerge reborn, a band with a sharpened sense of purpose, a stronger willingness to show off their riffs, and a kind of note-perfect harmony that had only existed in more truncated form in the past. Weiss is a kickass drummer—her aggressive, precise dynamic well surpassed the basic need for keeping time—but on Dig Me Out, the group’s first for Kill Rock Stars, her addition to the group brought out the best in her bandmates as well.

From Carrie Brownstein’s opening clash of chords that start off “Dig Me Out,” right through into the snap of Janet Weiss’ snare drum, and on into the introduction of Corin Tucker’s voice, as she belts out the song’s title at maximum lung capacity, every single detail locked into place with simultaneous precision and ferocity. It was loud. It was defiant. It was punk rock.

For Sleater-Kinney, playing their loudest and fastest was just one approach, rather than the entire template. For as much ferocity as Sleater-Kinney exhibited in a razor’s edge rave-up like “Dig Me Out” or “Words and Guitar,” they sounded much more comfortable in their own skin than on their first two albums. Never before had Sleater-Kinney seemed so huge and powerful, or for that matter, boundless — bold enough to juxtapose ballads like “Buy Her Candy” against full-throttle rockers like “Not What You Want,” and treating subjects like listening to records with the utmost importance on “It’s Enough,” while lampooning gender stereotypes in “Little Babies.” The qualities that led Greil Marcus to later dub Sleater-Kinney “America’s best rock band” crystallized on Dig Me Out; they were ready to step up to the next level.

Rating: 10 out of 10

The Hot Rock

The Hot Rock

(1999; Kill Rock Stars)

If Dig Me Out was the moment where all of Sleater-Kinney’s strengths converged into one powerful whole, The Hot Rock was when the trio began to explore more fully the depths of those strengths. Up until this point, Sleater-Kinney had unequivocally been characterized as a punk band, and that’s pretty much true. As punk albums go, Dig Me Out gets every note just perfect. But The Hot Rock is something different; it’s nuanced and a bit more abstract. There’s nothing on the group’s first three albums that sounds like the title track, a slow-burning post-punk number that uses a diamond heist as a metaphor for infidelity (I think?). Or “Get Up,” which finds Corin Tucker making an impressive transition between spoken-word verses and a powerful, roaring chorus. And I’m not even sure that on subsequent albums they attempted anything quite like “The Size of Our Love,” a slow, cello-laden ballad sung by Carrie Brownstein about being a cancer patient in love (and wasn’t featured in The Fault In Our Stars—missed opportunity, that).

The Hot Rock isn’t solely about experimentation, though; to suggest as much would be to imply that Tucker, Brownstein and Weiss were getting some stuff out of their system, but that wasn’t really the case. It’s an album with a more diverse array of sounds, and perhaps a greater number of risks than its predecessor, which means that it doesn’t hit every bullseye dead center. That doesen’t mean it doesn’t come close, though, and let’s be clear, it absolutely features some of the band’s best songs. One of those, “Start Together,” kicks off the album with as much of a rush as any album in their catalog, particularly as it launches into the surprisingly heavy chorus. And its closing track, “A Quarter to Three,” ranks as one of the band’s most climactic and emotional moments. It’s not a perfect album, but it’s close enough for that not to matter that much.

Rating: 9.3 out of 10

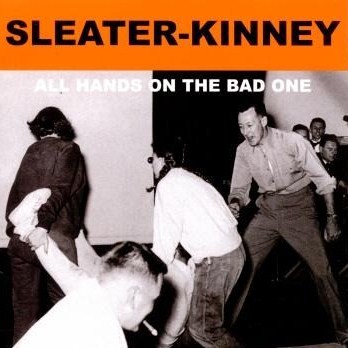

All Hands on the Bad One

All Hands on the Bad One

(2000; Kill Rock Stars)

With The Hot Rock, Sleater-Kinney had put a comfortable amount of space between themselves and their punk roots. All of a sudden, their music contained so much more breathing room—more Unwound, less Bikini Kill. And as much as they nailed that early punk sound, the trio seemed equally capable—comfortable even!—playing with structures and sounds in a way that might have seemed uncharacteristic just a few years earlier. So it would make sense if they were to continue on that path, and they did, just not without a bit of a diversion before they actually made that progression.

I’m loath to call All Hands on the Bad One a step back. It’s not a worse album than The Hot Rock, but it feels considerably more straightforward. It’s Sleater-Kinney at their most pop, as well as a return to the short jabs of punk rock they pioneered earlier on, with some brief bridges between the two, so as not to interrupt the cohesion of it all. The material hangs together pretty well, actually, but once you’ve heard space in a Sleater-Kinney song, you start to miss it when it’s not there. “Ballad of a Ladyman” isn’t by any means the most aggressive track here, but it still feels almost cluttered by comparison to the more streamlined punk tracks like “The Professional” or “Youth Decay.” Then again, “Milkshake and Honey” is unusually relaxed and even a little campy. The best way to define All Hands on the Bad One is that it sounds like the band had a lot of fun making it, and it shows—it’s an awful lot of fun to listen to (especially “You’re No Rock ‘n’ Roll Fun“). No, it isn’t their best album, but at this point we’re judging by fractions of points. Once Sleater-Kinney hit their stride, there wasn’t anything to hold them back.

Rating: 8.9 out of 10

One Beat

One Beat

(2002; Kill Rock Stars)

“Where is the questioning, where is the protest song/ Since when is skepticism un-American?”

If you were to base your impression of One Beat off of “Combat Rock,” its driving Side Two opener, you’d probably reach the conclusion that it’s the band’s most explicitly political album. You’d be partially right; that song, an indictment of the Bush administration, Iraq War and that fun revival of jingoism circa 2002, is one of the few times that Sleater-Kinney has addressed a political issue on such a wide scale. But it’s also considerably thoughtful for how huge and soaring it feels; Carrie Brownstein isn’t singing about Bush and Cheney being war criminals, exactly, but rather the idea that it shouldn’t be considered treason to have doubts about a country’s direction, and for that matter, surreal to hear a president try to reassure the country by telling them to go shopping. There’s also a line about “red, white and blue hot pants,” which I’ve always thought deserved a gold star.

But One Beat is also the most intensely personal album Sleater-Kinney has ever released. This is largely a result of Corin Tucker’s transition into motherhood, which in turn draws us into some places that hadn’t been touched upon in their previous albums. Lyrically, Tucker sings from a place of vulnerability, pleading with God for the health of her baby in “Sympathy,” or watching reports on the 9/11 terrorist attacks while she’s nursing her child on “Far Away.” And yet, her voice only sounds more powerful and commanding than before, her booming projection in the title track opening the album with a gush of energy and authority.

Most importantly, One Beat fucking rocks. This is a band that has sold t-shirts that say “Show Me Your Riffs,” and they’re not shy about lettings those licks fly on this album. It’s Sleater-Kinney embracing their badassery, albeit from a more measured and mature place. It’s not a punk album, it’s a rock ‘n’ roll album—one of the best of the ’00s, in fact. There are thunderous sounds all over “Light Rail Coyote” and “The Remainder,” and “Step Aside” and “Sympathy” embrace blues and soul better than basically any indie rockers have since. And though it’s just one of many albums the group recorded with longtime collaborator John Goodmanson, here they sound even more loud and powerful than before. It’s maybe a couple songs shy of being perfect (“Prisstina” and “Hollywood Ending” sound more like B-sides), but damn is it close.

Rating: 9.6 out of 10

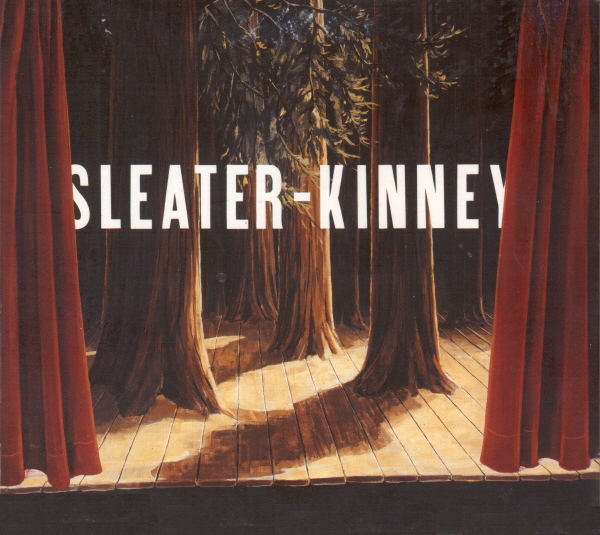

The Woods

(2005; Sub Pop)

In 2005, Sleater-Kinney were ready for a change. They took up residence on Sub Pop after a long partnership with Kill Rock Stars, and worked with producer Dave Fridmann after making four records with John Goodmanson. And in doing so, the group stepped well outside their comfort zone, to the point that they were pushing themselves to the point of exhaustion, frustration and near breakdowns while recording their seventh album The Woods. Some of that came out of the confusing and just plain weird suggestions that Fridmann would make, like this amazing chestnut: “This part should sound like Keith Moon—and then like a blanket being lowered over Keith Moon’s kit.” If you’re baffled right now, just imagine how Janet Weiss felt!

Here’s the thing, though: It worked. The combination of a change of venue and collaborators, along with a new push to create something more challenging than they had before resulted in exactly that. Sleater-Kinney released two game changers in their career: Dig Me Out was the first; this is the other one. No other Sleater-Kinney album sounds like this one: a booming and explosive album of rock music that finds the band transcending indie rock and living up to the thunder of their personal heroes in The Who and Led Zeppelin, while displaying the avant garde influences of Television and Sonic Youth. It’s defined in large part by just how loud it is—if you’re not ready for the massive clap of distortion that opens first track “The Fox,” it’s downright startling. And everything that follows feels extremely physical and visceral; you don’t just hear it, you feel it. Even “Modern Girl,” a jaunty ballad in which Carrie Brownstein sings about buying a donut with a hole “the size of the entire world,” slowly disintegrates into a toxic muck of distortion and feedback.

If the first listen is about how many exclamation points the band stacks up on these 10 tracks, the second listen to The Woods is about how incredible a performance Sleater-Kinney gives here. Carrie Brownstein is arguably the album’s MVP, if for no other reason than her intense, seething vocal lead on “Entertain,” one of the band’s most triumphant rock anthems. Then again, Sleater-Kinney has always stood strongest as a unit, and here, there’s no stopping them.

Rating: 10 out of 10

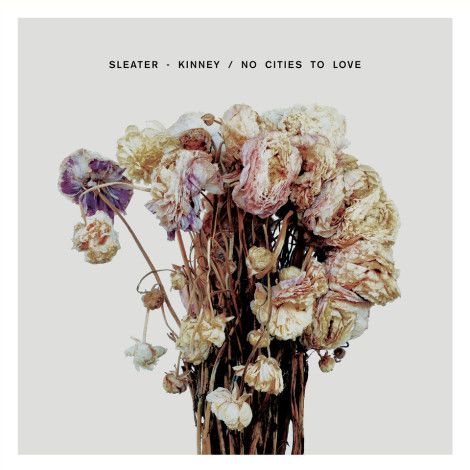

No Cities to Love

No Cities to Love

(2015; Sub Pop)

After this feature was initially published, Sleater-Kinney released their eighth album, No Cities to Love, as well as embarking on an extended series of tour dates. It would have proven significant for the sole reason that a great band had returned after 10 years of inactivity, hiatus and the possibility that they were permanently broken up. But it was much more significant than that for a very important reason: It’s a phenomenal album. To Sleater-Kinney’s credit, they left on their highest note possible with one of the best albums they ever released. Their return, however, was not a drop in quality in the slightest. No Cities to Love isn’t as immense and imposing as The Woods, but it’s nonetheless a top-tier Sleater-Kinney album. They sound confident, comfortable as a team, yet considerably looser in certain parts. On a track such as “Bury Our Friends,” they’re just as heavy as they were before making their (temporary) exit. Yet on “A New Wave,” they sound like they’re having fun playing music together more than making a statement, and it’s infectious. The most telling song, however, is “Surface Envy,” on which Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker harmonize, “We win/We lose/Only together do we make the rules.” It’s a statement of purpose and intent—they’re playing on their own terms. I couldn’t imagine it any other way.

Rating: 9.2 out of 10

The Center Won’t Hold

(2019; Mom+Pop)

Up until 2019’s The Center Won’t Hold, none of Sleater-Kinney’s albums could have been accurately described as “divisive.” Which doesn’t mean they appealed to everyone, just that they didn’t evoke equally strong positive or negative feelings. But the band’s ninth album is wrapped in a variety of circumstances that contribute to some of that discourse. For one, the album was produced by Annie Clark, aka St. Vincent, whose penchant for art-pop conceptualism is a bit outside of Sleater-Kinney’s musical sphere, and for another, it’s the final album with drummer Janet Weiss, and the splintering of the band makes it a bittersweet listen as a result.

There are a few more synths, a little bit more pop polish, but ultimately? It sounds like Sleater-Kinney. Clark’s production doesn’t remove anything from the band’s sound, and what’s added is mostly subtle. When they’re on, they’re on: The opening trifecta of the title track, “Hurry On Home” and “Reach Out” are three dynamite tracks in a row, sounding like the dialed-in, hyper-charged band they’ve always been. And even on subtler moments, like the gloomy goth-pop of “The Future Is Here,” their knack for melody is on full display, not to mention Corin Tucker’s vocals, which only seem to sound stronger with time. What feels different about this, ultimately, is that the band tends to favor a new approach, trying out new things—which is good!—while dialing back some of the things that made their past albums so exciting. Tucker takes lead vocals on fewer songs than Carrie Brownstein, and there aren’t as many opportunities for Weiss to showcase her strengths as a drummer. And a few songs, like “Bad Dance,” just aren’t that good. Every band will inevitably undergo change and some growing pains, and for Sleater-Kinney it might have been inevitable. You can hear them on The Center Won’t Hold, but you can also hear a band determined to keep moving and evolving in spite of them. You can hear it as the end of the Sleater-Kinney you knew, or the beginning of one you’re just becoming acquainted with—both are probably true.

Rating: 8.3 out of 10

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.

Sleater-Kinney

Sleater-Kinney Call the Doctor

Call the Doctor Dig Me Out

Dig Me Out The Hot Rock

The Hot Rock All Hands on the Bad One

All Hands on the Bad One One Beat

One Beat