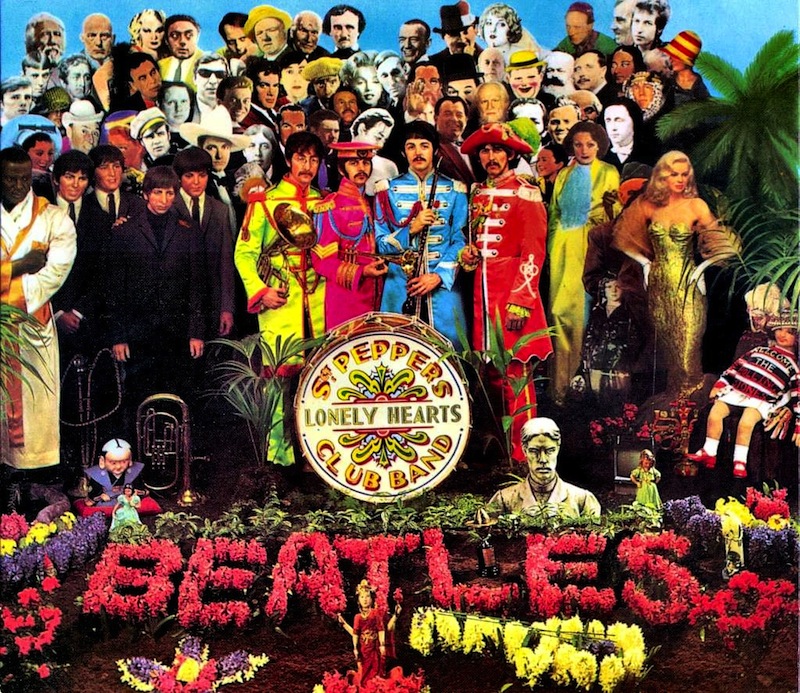

The Beatles : Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

It would be impossible for me to say anything about Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that could possibly do justice to its reputation. It’s been hailed as one of the most (if not the most) influential rock albums of all time, driven predominantly by Paul McCartney’s compositions. Some regard it as the first concept album even though the concept is somewhat abandoned after Billy Shears (Ringo Starr) finishes his bounding little song. It’s the first album with printed lyrics. It spawned a really awful movie of the same name starring Peter Frampton, a pizza place in Orange County (Sgt. Pepperoni’s Pizza) and a delightful animated jaunt that peppers my memories of grade school. The album cover designed by Peter Blake has been often parodied or copied by the likes of Frank Zappa, The Simpsons, Eric Idle and snappy comic book creator Mike Allred.

Even with these niceties and bits of minor trivia out of the way, it would be hard to say anything unique about the album’s history, but at the risk of sounding redundant, here it goes.

Having grown tired of touring and still feeling the furor over a certain comment involving Jesus, The Beatles intended to make an album that could tour for them. McCartney decided each member of the band should create fictional alter egos and that the ensuing album would be a performance by the fictitious house band of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club. The person-packed album cover was to simulate a show by the title group. Recording of the album began December 6, 1966 and over the next 129 days, the Fab Four and producer George Martin would experiment with layered sound effects and elaborate arrangements creating an album that sprawls magnificently and daringly in different directions. With that said, picture yourself in a fictional nightclub, with floral arrangements and powder blue skies. A stage full of cut-outs and four gaudy outfits, worn by some Liverpool guys. At this performance of the Lonely Heart’s Club band, celebrities have shown up in droves, but for legal reasons (read: he wanted to get paid), actor Leo Gorcey was painted out. And being for the behest of EMI, Jesus Christ, Hitler and Gandhi couldn’t show up for the show either.

After the rustle of the gathered crowd (the applause and laughter taken from a live performance of the hit Brit comedy show “Beyond the Fringe”), a blast of distorted, jangling guitar and pulsing drums is coupled with McCartney’s enthusiastic, wailing greeting on the album’s title opener. A French horn arrangement joins the song as Paul and John share vocal duties over guitar squeals and fuzzy power chords. The band segues into the poppy, bounding “With a Little Help From My Friends.” Written by Lennon and McCartney expressly for Ringo to sing, the bubbling bass and hopping piano aptly accompany Ringo’s pleading, somewhat downbeat vocals. Joe Cocker would cover the song a year later, but his delivery wasn’t quite the same.

After “With a Little Help From My Friends,” The Beatles basically get on stage instead of the club’s band and begin with a BBC-banned tune that helped name a famous Australopithecus afarenis, “Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds.” The song was inspired by a painting by a four-year-old Julian Lennon which evolved in John’s mind into an expansive, swaying, Lewis Carroll revelry. This was one of my personal favorite tunes as a child after seeing the colorfully animated sequence in Yellow Submarine. I had no idea what psychedelia was nor did I catch onto the incidental drug reference until high school, but the images sure were pretty and to this day, any time I’m enamored by a lovely looking girl with the sun in her eyes I hear the tip-toeing melody of the song’s harpsichord.

Paul makes a cute-pop, hand-clapping contribution in the form of “Getting Better,” a song I remember hearing my mom sing sporadically around the house on countless occasions. I think my mom liked it because it was optimistic for the most part and redemptive. I enjoyed the song initially because I loved hearing how happy my mom’s voice could get, but I later came to love it for the same reasons she did.

Strangely, the head-swaying “Fixing a Hole” and the circus poster-inspired “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” remind me of rainy weekends as a child and my mom humming “Getting Better.” The haunting runaway tale “She’s Leaving Home” – a song in which none of the Beatles played instruments – reminds me of high school rainy weekends and gray bay area skies (which are comparatively brighter than even clear English skies). John’s parental backup vocals always recall every rueful comment my folks made in my presence to elicit feelings of guilt.

George Harrison’s second Indian-sounding recording for the band “Within You Without You” is an exotically optimistic inspirational tune; a Tandoori Chicken for the Soul, if you will. Over a driving and comparatively spare arrangement, George’s drifting voice reminds that “With our love – we could save the world” and that “life flows on within you and without you” (ob-la-di?).

The bounding big band melody, bell tolls, quaint domesticity and clarinet arrangements of “When I’m Sixty-Four” open and close pleasantly before the parking ticket punch of “Lovely Rita.” There’s something about the way Paul belts out the “maid” of “Lovely Rite meter maid” that has always made this song endearing. The fading pants and groans of the parking attendant devotional give way to a cock crow and John’s cereal commercial-inspired “Good Morning Good Morning.” The playful lyrics and vocal patterns drift off into bizarre barnyard mayhem.

On the penultimate track, that title band that’s been missing for nine songs makes another appearance playing a straight rock version of the album opener. Rather than saying hello, Paul, John and George sing a hurried goodbye, parting regretfully but politely to an enthusiastic crowd of cut-outs. The adulation bleeds into the ambitious, also BBC-banned, multi-layered masterpiece/end piece “A Day in the Life.” The song was inspired by two reports John read in the news; one involving the car crash death of Guinness heir Tara Browne (“He blew his mind out in a car“); the other involving the 4,000 holes a road surveyor counted in the roads of Blackburn who noted that the amount of material needed to patch it all up would be enough to fill the Albert Hall.

The song transitions gorgeously from John’s somber verse and chorus through a 41-piece orchestral swell into Paul’s driving bridge, which apparently was intended for another song. Even as the tone shifts between the two distinct parts, the song somehow remains a cohesive whole. A mad, escalating swell of sound overtakes the fading echo “I’d love to turn you on” before three pianos strike the same chord simultaneously. The grand, triumphant note resonates 42 seconds into silence before a final round of incomprehensible group babbling erupts saying something that sounds like “Would not have it any other way.”

“A Day in the Life” has always been a pretty lachrymose song for me, an emotionally overwhelming experience that I can’t quite explain and a fitting finale to an album so important and ambitious. Maybe it’s the lonely acoustic guitar that ushers someone into the song or the occasional punctuations of piano, maybe it’s John’s gray-sky voice juxtaposed with Paul’s happier delivery or maybe I can’t help but get misty in light of the song’s sheer scope. I don’t know. What I do know is that though the song makes me feel something, it doesn’t make me feel something bad. It makes me nostalgic. It reminds me of my folks smiling and the one time I saw my dad cry, of my mom singing while cooking and of my childhood in front of a glowing television.

I wonder at the end of another day if I’ll forget how much I cherished those little things. And I realize that’s the reason, as peculiar and perhaps generic as it may sound, that this particular song and this album leave my vision a little misty.

Similar Albums/ Albums Influenced:

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Are You Experienced

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Are You Experienced

The Beach Boys – Smile

The Beach Boys – Smile

Kinks – The Village Green Preservation Society

Kinks – The Village Green Preservation Society