The First Tindersticks Album was both a record out of time and ahead of its time

When Tindersticks released their 1993 debut album, they seemed worlds apart from landscape of the moment. In the U.S., grunge had dominated radio for well over a year, the success of Nirvana and Pearl Jam giving rise to readymade post-grunge talents such as Candlebox and Collective Soul, and eventually even some transatlantic exports. But the UK, in 1993, was wrapped up in the early mania of Britpop, Blur and Suede having kicked off a music-tabloid sensation through their singles “Popscene” and “The Drowners,” respectively, each released the previous spring. By the time the well-coifed Brett Anderson adorned the cover of Select magazine with the caption “Yanks Go Home!”, Britpop had assuredly arrived.

It must have thrown more than a few readers for a loop when British magazine Melody Maker made neither Blur’s Modern Life Is Rubbish nor Suede’s self-titled debut album its Album of the Year. In fact, Blur didn’t even make the list. Rather, the honor went to Tindersticks’ self-titled debut, later known as The First Tindersticks Album, a 21-track album of coolly crooned chamber pop, a set of songs at once out of time and ahead of their time, anachronistic but seemingly not belonging to any era at all. The opening lines of leadoff track “Nectar” feel similarly detached from its time; though the Internet was still a novelty, something about Stuart Staples’ croons of “My letters sit on your windowsill, yellowed by the sun” feels like a transmission from a bygone era. It’s charming and romantic, the words of a man who’s known the sting of a broken heart, and who might be responsible for a few himself.

The success of the album caught the band off guard, the sextet having spent more than half a decade making music under a different name to very little attention. Vocalist Stuart Staples, keyboardist David Boulter, guitarist Neil Fraser, violinist Dickon Hinchcliffe and drummer Alistair Macaulay had spent four years cultivating their sound as Asphalt Ribbons, recruiting bassist Mark Colwill in 1991. They made a fresh start with a name change, Staples choosing Tindersticks after seeing the word on a box of matches on a Greek beach—so the story goes—and the result was like hitting reset. With a blank slate and no new expectations for their rebranded project, Tindersticks unwittingly landed with an impact much greater than the hushed tones of their ballads would suggest.

“The first album was a really fresh, wonderful time,” said the band’s David Boulter in an interview with The Quietus. “We’d spent the years growing up, being in bands, trying to be successful. When we gave up trying, everything seemed to happen.”

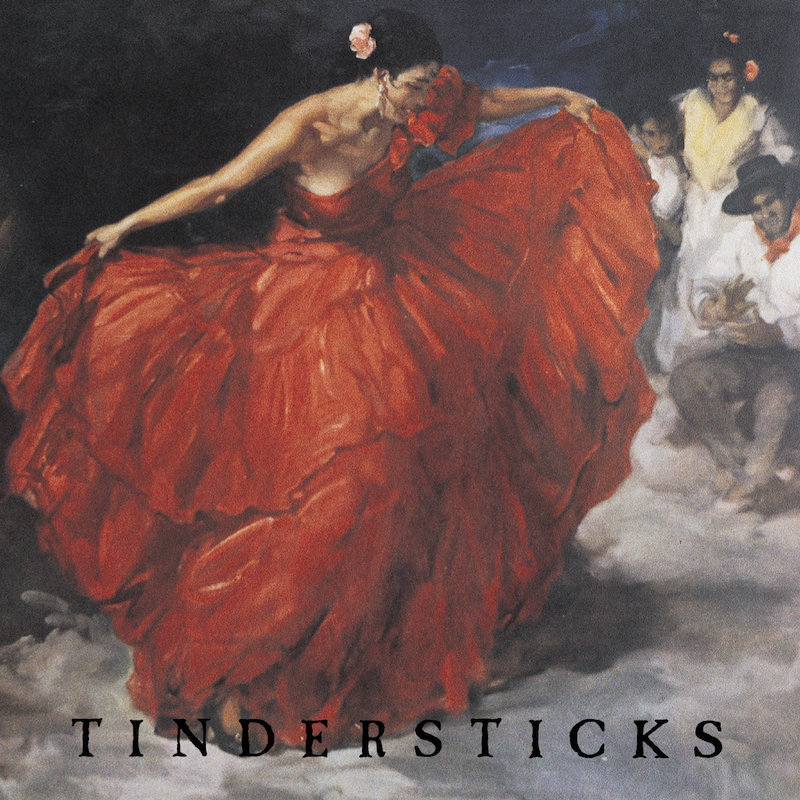

The First Tindersticks Album, now reaching its 25th anniversary, is beautiful. It’s also dark, romantic, lushly arranged and unexpectedly climactic. This isn’t music that introduces itself with bombast, but harbors something powerful just waiting to be unleashed. Given the omnipresent strings that appear through the album, along with Staples’ buttery croon, it’s easy to imagine the band dressed to the nines, performing on stages draped in red curtains. When the album was released, there wasn’t much in contemporary music that felt like it belonged to the same music as the music of Tindersticks. Their reference points were poetic troubadours such as Scott Walker and Leonard Cohen, or gothic crooners like Nick Cave. And Staples’ warmly affecting vocals gave a certain charm to even their most sinister offerings—of which there were many. The Nottingham, UK band occupied their own unique stylistic space. The single “City Sickness,” perhaps the album’s most celebrated track, spoke to a disconnection that, in many ways, defined Tindersticks: “The centre of things where everything stems is not where I belong.”

Much like Cave or Cohen, Tindersticks present frequently unglamorous things in a glamorous package. They’re beautiful songs, but they’re splattered with all manner of fluids, cleansing, disgusting or otherwise: “Whiskey & Water,” “Raindrops,” “Tea Stain,” “Blood,” “Nectar” and, yes, even “Jism.” On “Whiskey & Water,” the band taps into a stormy intensity that contradicts their suave exterior, while the complementary “Tied” and “Tie-Dye” offer different variations on the same gothic chamber-pop melody. The latter two songs, while certainly among the most darkly cool tracks on the album, are likewise some of the most subtly horrific, Staples gradually expanding a mysterious but sinister narrative: “The sheet that was cut caught the blood/ Was opened, dried and stretched out/ Hung on the wall.” And though the album often finds Staples lost in the haze of heartbreak and several drinks deep, he more often than not offers a glimpse at a monster that lurks just beneath the surface, as heard in “Piano Song”: “Shut up, I’m thinking… I’m at my strongest only when I’m weak/ And I give you those bruises just by talking to you.” It’s as much about building a vivid world as it is about finding an out.

“There was this sense of non-reality about those first two records,” Staples said in an interview with The Guardian in 2008. “Most of us had jobs, so it was purely about escape—rushing home from work with that hunger to get things done.”

Tindersticks’ debut overwhelms. There’s also a lot of material here, considerably more than most bands would be bold enough to release on their debut. Even more remarkably, it’s uniformly breathtaking. With 21 tracks, the record could have easily been spread out over several releases, and the fact that the band’s similarly excellent follow-up from 1995 is also titled Tindersticks only complicates matters. Yet the brilliance of the album—the overflowing creativity and seemingly bottomless well of impeccable songs—came about because of necessity. The band essentially recorded everything they had; after all, who knows when they’d be able to do it again?

“I think when we made it, we’d basically recorded a demo version of it in our kitchen, which in some ways to me sounds better than the actual album,” David Boulter told Noisey. “But we found the money to book a studio for ten days. And we thought this might be our only chance to make a proper album. We recorded everything we had, basically.”

The great irony of Tindersticks’ debut is that the well never ran dry. In fact, while many of the bands vying for that same 1993 Album of the Year honor have broken up, reunited and broken up again, Tindersticks are still going, arguably as strong as they’ve ever been. Yet while they never followed this record with anything quite so overwhelming or grand, they’ve never released a bad album, and for that matter, spread out into the world of film scoring through a series of collaborations with director Claire Denis. They even maintained the same lineup for well over a decade, an accomplishment which scant few bands can claim.

Though Tindersticks once seemed out of time, ultimately they proved to be ahead of their time. Their influence has spread throughout underground music over the past 25 years, and the kernels of too many indie-rock and -folk songs to name can be found here. “Paco De Ranaldo’s Dream” is an obvious precursor to Belle and Sebastian’s “A Spaceboy Dream”; “Nectar” is, well, pretty much every song by The National. If imitation is flattery, then the compliments seemingly never cease. It’s easy to see why—a wild spirit of creativity is what drives The First Tindersticks Album, a huge and simply gorgeous piece of work that challenged the underground by offering something, above all, elegant.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.