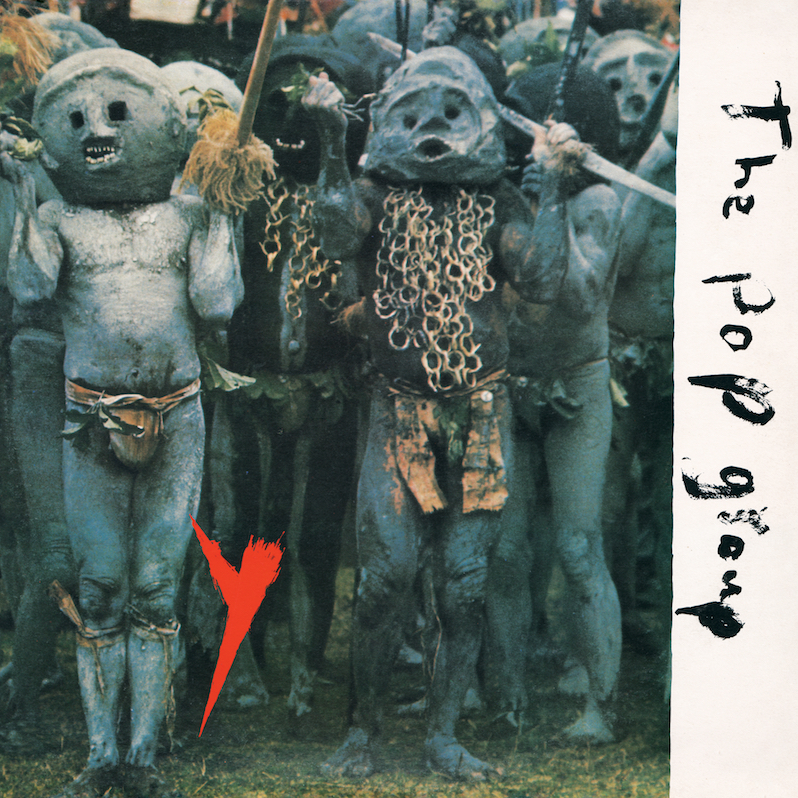

How The Pop Group’s ‘Y’ captured a joyful chaos

“Amidst a blur of flailing limbs & insane energy, I detected a kernel of something special. I was entirely alone in this, the Stranglers audience greeted them with indifference or outright hostility.” – Dick O’Dell, manager, on seeing The Pop Group live for the first time

***

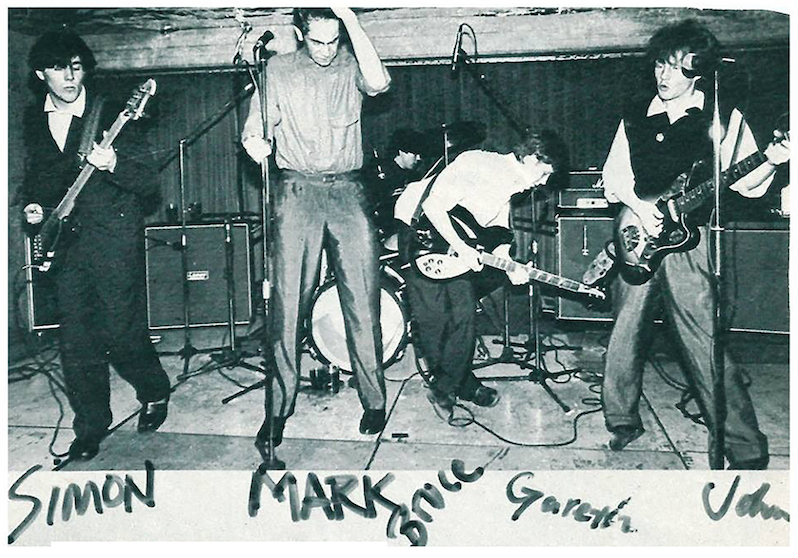

“We Are Time,” the last track on the first side of Y, the 1979 debut album by Bristol’s The Pop Group, packs a lot into six and a half minutes. By the standards of punk rock, six minutes would be enough time to stuff in at least three songs, though “We Are Time,” somehow, feels like more than that. Driven by the taut interplay between Simon Underwood’s funk bass groove and guitarist Gareth Sager’s reverb-heavy surf-guitar riffs, “We Are Time” embarks on an interdimensional transport through punk and funk, dub and jazz. Mark Stewart’s distorted voice echoes in from some distant, unseen base. On the surface it feels like chaos, but its elements all come together into one collision of strange, violent, extraterrestrial joy.

Nick Cave put it better than most when he described The Pop Group’s music as “manic, paranoid, violent, painful music,” and meant that as a compliment. And Cave, it should be noted, had few kind things to say about the post-punk bands he was hearing in the UK of the late ’70s and early ’80s (“We felt like we were gangbanged by a pack of marshmallows”). The Pop Group didn’t give their audience the option of tepid disappointment. It was either utter shock or absolute, unfiltered euphoria, both of which flood the 41 minutes of their debut album, Y.

There’s no blueprint for an album like The Pop Group’s Y. The music is a bright bolt of energy more than something you can get your hands around, an expression of sonic ecstasy that exists outside of structural conceits and constraints. It became “post-punk” by definition, if only because music this radical rendered punk obsolete. Johnny Rotten preached anarchy; The Pop Group practiced it. Which in many ways was a byproduct of not having any instruction or belief that they couldn’t.

“We were really young and we just had ideas and sort of amazing different music that we loved, everything from James Brown to Funkadelic to Nico, John Cage, Stockhausen and Ornette Coleman,” says Sager. “And you know we just because we were young and naive we just thought you could mix all that stuff together. You know, even if you were 25 you wouldn’t think of mixing all those things together.”

If Y didn’t have a blueprint, however, it absolutely had a backbone: Funk. It’s in the taut, yet rubbery groove of “Thief of Fire,” or in the scratchy noir of “Words Disobey Me,” or in the skrony no-wave freakout of “Don’t Call Me Pain.” Funk courses through The Pop Group’s veins—as does jazz, noise, reggae, essentially any record they could get their hands on. And even as punk was breaking, sounds from well beyond their own backyard were capturing their attention, like the polyrhythmic groove of Talking Heads and the fluid guitar interplay of Television. And before putting to tape their own unique sounds, Stewart, Sager, Underwood, Bruce Smith and John Waddington spent their teenage years going to youth clubs in Bristol, seeing and hearing the music of Kool & the Gang and Parliament.

“Ridge Farm, first recording day, first song. Gareth Sager said ‘Listen to this!’. Played on Danset (record player) James Brown, Soul Power, Superbad! I started dancing. Gareth said ‘Now you’re ready’. Then we did ‘Thief of Fire’.” – John Waddington, guitar

In fact, it was funk more specifically than punk in which The Pop Group found their spark.

“We were real, what they call now, ‘crate diggers’ on the way home from school. And our best friend had had a Bristol band called the Cortinas. He used to play the Roxy and everything, and The Pop Group formed coming home from one of their concerts,” Stewart says. “We said ‘let’s make a band—punk’s already happening, let’s throw in the stuff we’re hearing on the streets of Bristol.’ Like the funk I was listening to in the funk clubs—we were all going to see War and Parliament. There was a big funk thing in Bristol just before punk.”

“Being in Bristol, we all went to nightclubs when we were really young,” Sager says. “You won’t believe it, but we were able to go to nightclubs when we were 14 years old. You know. I mean you were meant to be 18, and I looked about eight but you still got into them somehow. But all these clubs were playing soul music.”

When The Pop Group were preparing to record the songs that would become Y in 1978, their original plan was to work with The Velvet Underground’s John Cale as producer and then have it engineered by someone with more of a reggae background. That never panned out, however, and instead the band ended up enlisting Dennis “Blackbeard” Bovell, a dub producer, in his first non-reggae project. What ensued was a period of energy and intensity that created a listening experience to match. The sounds on Y are a mix of alien and familiar, hooks turned upside down and cacophony made immediate. And as a lyricist, Stewart was just as voracious a crate-digger of ideas: myths, philosophies, critiques and surrealism, each highlighted and deconstructed as well, much like the music itself.

“[Producing Y] gave me the opportunity to flex my production potential on the magnificent compositions they presented me with” – Dennis “Blackbeard” Bovell, producer

Stewart describes their joyously explosive sound as “a crime of passion,” a moment of inspiration that might not have been replicated had it not happened when it happened, and with the right person behind the boards. But with Bovell, The Pop Group found a natural collaborator, someone that brought the right energy out of the band as much as he was able to feed it right back to them.

“It was basically a kind of Polaroid of that madness at that time. When we got into the studio with Dennis, he was as mad as us,” Stewart says. “So we wouldn’t sleep for like for two nights, and we’d be sitting there in our pajamas, cutting hundreds of bits of tape backwards and forwards, and Gareth was climbing across these really expensive mixing desks like like a monkey on the Starship Enterprise.”

Punk, for The Pop Group, wasn’t a sound, it was a feeling—a transfer of energy, inspiration, even agitation, that could be catalyzed and transformed into something new and productive, destructive, inspirational or aspirational. Y was punk, even if it didn’t sound like the Pistols or The Damned, simply because it didn’t adhere to expectations or decorum. They created something, and deconstructed something, and that visceral, emotional feeling was for the listener to take with them and do as they saw fit.

“Back in the punk days it was really about everybody just getting some energy and using it however they wanted in their lives,” Stewart says. “It wasn’t about the person on the stage, it wasn’t about somebody dictating on the phone to somebody, you know. It was about just opening the door.”

Y has been reissued for its 40th anniversary via Mute, featuring a wealth of rare material including the previously unreleased set of recordings, Alien Blood, and the Y Live recording, featuring tracks recorded during performances in New York, London, Sheffield and Manchester—not to mention the “She Is Beyond Good and Evil” single, which was added to later reissues of the original album. It’s the climactic reward of a quest between the band and their management to re-acquire the masters and rights to all of their recorded output, which is now back under their care. And after 40 years, there’s still very little that sounds much like it. You might hear a trace of some classic dub in one moment, the bass pop of Bootsy Collins in another, the guitar scratch of Gang of Four if you tilt your head just right and squint. But The Pop Group’s debut remains a piece unto itself, a fusion that nobody else even thought to create before. Even hearing the old tapes again, Stewart said his immediate reaction was, “What the fuck?!” (“My oldest self is looking back at my youngest self and saying ‘Well done, mate’,” he adds.)

“On many occasions, all of us including Dennis, were in unchartered waters and that is what gave it spirit, and made a seminal record. I don’t think we were trying to be different.” – Simon Underwood, bass

For a first time listener—even 40 years after the album’s release—Y is a dizzying, overwhelming clash of sounds. Which in turn led to various misconceptions about what The Pop Group’s aims were. The name originally came from an offhand comment from Stewart’s mother (“Oh, Mark’s forming a pop group,” he quotes her as saying, in previous interviews), not intended as an ironic statement or some kind of “The Aristocrats” joke. Still, the band got used to being called willfully bizarre or even anti-pop—even if that was far from their actual intent.

“I think [people thought] we were devotees of Captain Beefheart, and that we were just trying to be weird,” Sager says. “But you know, when you’re limited with what you can do, that makes you inventive. And that’s exactly what we did.”

“There’s big riffs, of course! It sounds like Zeppelin to me!” Stewart says, pointing to the melodic immediacy of “Thief of Fire” to emphasize his point. “John, the guitarist, is a perfect sort of popsmith. Him and Keith Levene, who formed The Clash, just ooze out these kind of pop hooks. Even the craziest thing, ‘Blood Money’, sounds totally out there because we took it backwards and forwards. But if you hear the very early stuff, it was very simple, power-pop songs. But we decided to do loads and loads of dubs and run the tape backwards. Suddenly something mind-blowing happened when us and Dennis panned something through banks and banks of Jamaican soundsystem boxes. We weren’t precious. And we still aren’t precious.”

That lack of preciousness—that willingness to embrace the unexpected or the transgressive—is ultimately the gift that both Sager and Stewart would like to distribute to new listeners and younger generations. They do make pop music—sometimes it’s at the forefront of their songs, sometimes it takes a little digging—but the greatest takeaway from Y is that music not be defined by format or structure. Perhaps those are loose guidelines, even theories around which to create something, not the thing in itself. But it helps to have the optimism and naivete of youth to not let caution stop you.

This stunning, inimitable piece of music exists because these five musicians and one producer allowed freedom and curiosity to guide them. Which, they still believe, is a far better path to follow than to let expectations dictate the limitations of your art.

“Especially now, nobody really makes money from music, so there’s absolutely no rules,” Sager says. “You don’t have to sound like Radiohead. You can sound like a radio, going fucking mental. I never understood why people just do strange versions of things that already exist. You know, we were teenagers. It’s teenage expressionism, really.”

“Basically, you know, my whole life I’ve been making stuff for my own for my own perverse pleasure,” Stewart adds. “I mean I’m trying to make tough stuff that I’d want to hear.

“My favorite song [on Y] and the kind of motto in my life is ‘Thief of Fire’,” he continues. “If somebody says something is dangerous, or we shouldn’t go there…well, I’ll go there.”

***

“My hope is that this record will continue to inspire others in their own endeavours and strive to be original in the art they make. Mediocrity begets more mediocrity.” – Bruce Smith, drums

The Pop Group: Y

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.