I stopped listening to Nirvana‘s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” when radio liberated me from ever having to make that choice again. It would simply always be there, a ubiquitous remembrance of a generational icon lost too soon, the flickering flame of a long-past musical moment that would assuredly never get to rest. On rock radio, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is more than a standard, it’s a guarantee—like “Hotel California” or “Stairway to Heaven” before it (or “Enter Sandman” concurrently). As the addition of new bands to modern rock playlists slowed down and all but stopped altogether, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” remained. Whether or not you needed it, you’d know where to find it.

After playing it more than 100 times, Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain himself found himself expressing a similar desire for space from the song. A rock ‘n’ roll anthem patterned after both Boston’s “More Than a Feeling” and The Pixies, it’s a powerful song—a simple but forceful piece of music that could make you believe that its nonsense lyrics (Teen Spirit being the name of a deodorant in the early ’90s, and its chorus a catchphrase Cobain often said at parties) actually said something about disaffected youth and teen rebellion. So powerful, in fact, that between 1992 and, well, now, it’s essentially remained part of the fabric of popular culture, never far from the surface and only a turn of the dial away from reaching your ears. It’s not necessarily that Cobain no longer had any appreciation left for the song, but eventually it becomes a distraction, even a reminder of the kinds of shallow and prejudiced fans he didn’t want anywhere near the band’s music. But if he didn’t hate it, he certainly started to resent what it represented.

“Everyone has focused on that song so much. The reason it gets a big reaction is people have seen it on MTV a million times. It’s been pounded into their brains. But I think there are so many other songs that I’ve written that are as good, if not better, than that song,” Cobain told Rolling Stone in 1994. “But I can barely, especially on a bad night…get through ‘Teen Spirit.’ I literally want to throw my guitar down and walk away. I can’t pretend to have a good time playing it.”

The baggage that accompanied “Teen Spirit” would have never attached itself to a song like “Tourette’s,” a chaotic, 95-second tantrum of noise-punk and unintelligible shrieking that arrives just before the end of Nirvana’s second album In Utero. You also can’t say that about “Milk It,” the sludgy, Jesus Lizard-like round of mumble-and-pummel that occurs a few tracks earlier, or even “Very Ape,” the relatively brief, relatively accessible but abrasive punk groove that slides in at the beginning of side two.

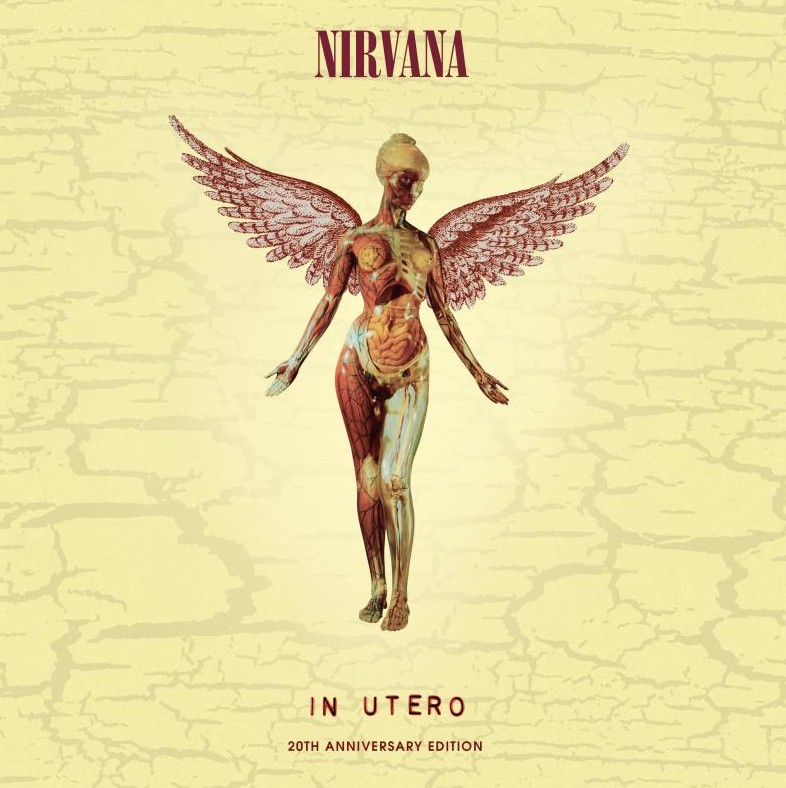

In Utero, Nirvana’s third album, at times still feels like an act of hostility. It didn’t necessarily have the effect of pushing people away—the video for first single “Heart Shaped Box” regularly appeared on primetime MTV, and the album has sold 15 million copies worldwide, a number that’s not so shocking in the context of the runaway success of their 1991 album Nevermind. But it doesn’t sound like a hit album so much as an investment in extremes, a tangle of feedback and shrapnel that challenged its listeners to engage with its ill-tempered gnashing.

Cobain himself was often regarded as mercurial after the success of Nevermind, in part because of his growing heroin habit, which he developed while self-medicating for his chronic stomach pain (which, for that matter, would have made anyone ill-tempered). He had widely publicized confrontations with Axl Rose and Eddie Vedder, and included a disclaimer in the group’s 1992 outtakes collection Incesticide, which read, “If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the fuck alone! Don’t come to our shows and don’t buy our records.“ If he came on strong or perhaps defensive, it’s mostly because he saw the hazards that accompanied fame more clearly than ever.

In Utero wasn’t necessarily intended to be an act of antagonism, but if it scraped a few barnacles off the hull, all the better. Cobain, Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl simply wanted to make a record that they enjoyed listening to, but given the left-field cacophony of some of Cobain’s actual favorite albums—Scratch Acid, Butthole Surfers, Flipper, Raw Power—that always had a high probability of leaning away from the commercialism of their breakthrough. Enlisting engineer Steve Albini to record the album as a means of reclaiming whatever punk cred they lost by selling a few million records, the band decamped to Pachyderm Studios in Minnesota, where sessions were relatively easy and productive, perhaps because the pile-up of snow outside dampened the possibility of doing much else. And in its aftermath, a sort of telephone-game disagreement over the album’s mixing arose, eventually resolved with mastering engineer Bob Ludwig. But Cobain, insistent on not recording Nevermind for a second time, remarked that “The grown-ups don’t like it.”

If hostility wasn’t the intention, however, Cobain had plenty of fingers to point just within the first song. “Serve the Servants” is elegant, equal opportunity aggression; against Grohl’s thick snare whacks and a rusty arpeggio that scrapes up next to two meaty power chords, Cobain takes aim at just about everyone that comes to mind. Critics, fans, his father, even the image of Nirvana itself. “Teenage angst has paid off well, now I’m bored and old,” he sneers in the song’s opening line, affirming that the smell of Teen Spirit had indeed turned stale and fetid.

In Utero isn’t uniformly harsh or violent, but many of its most interesting moments are. “Scentless Apprentice,” inspired by the novel Perfume, one of the album’s most aggressively squealing noise-rock standouts, its churning riffs reminiscent of The Jesus Lizard’s Goat. “Milk It,” likewise, is aggressive, hostile, sludgy and huge, juxtaposing dissonant, disquieting verses against a deafening eruption that finds Cobain barking “Doll steak! Test meat!” It’s easy to hear how a song like this could have played a significant influence on metal bands like Thou, who covered it pretty faithfully a few years ago without changing their approach.

Two songs on In Utero are on some level rewrites of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” reworking a similar chord progression to wildly different ends. “Rape Me” once again finds the band drawing closer to their most confrontational instincts, Cobain shredding his throat through an anti-rape screed that was wildly misunderstood and purposefully provocative, though that didn’t prevent Saturday Night Live from airing the band’s performance of it. “Dumb” is the other one, a quieter ballad that seemed to predict their own Unplugged performance with an accent of cello.

In Utero still had hits, however. “Heart Shaped Box” is one of them, not necessarily the most commercial of the bunch but by all means one of the best. When the band released it as the first single, my 11-year-old grunge-obsessed brain registered it as suitably kickass, even with its cloak of darkness, compounded by the haunting Anton Corbijn-directed video. If anything, the sinister tone of the song provided a better entry point to the album than any other song could have.

The album’s other big single, “All Apologies,” closes the album by tapping into something much brighter and, though sardonic, far less cynical. With its major-key melody and chorus of “In the sun, I feel as one,” it’s strangely hopeful and harmonious; Nirvana were never corny enough to slather their songs in “namasté” affirmations, but more than any other song here, it feels like they open a door toward something more hopeful. You can almost hear Cobain crack a smile.

Had Cobain not died by suicide in spring of 1994 and continued to make music, the fourth Nirvana album very likely would have changed course as well. He insinuated in interviews that it probably would have sounded something like R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People—less distortion, more muted tones. It’s fascinating to imagine what shape that would have taken, though their Unplugged in New York album at least offers something of a preview. It would have been a palate cleanser for the throttle and scrape of the harshest moments of In Utero, which in turn helped remove the taste of a megahit that was destined for classic rock radio the moment they stopped the tape.

Despite being the last music that Nirvana released before Cobain’s death, it doesn’t scan as a warning sign or a cry for help or anything so cliche. That element is there, certainly, if that’s what you’re looking for. But, ending on their brightest piece of music and loaded with one trapdoor after another, it feels—decades later—like an effort to fuck with perceptions of who they were and what their music truly was. It’s as if they were testing how far those fairweather fans were willing to follow them, no matter how much this music got under their skin. There are other ways to draw attention away from a hit song you can’t stand to hear anymore, but few as wickedly satisfying.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.

Always a pleasure to read an article, in current times, about this band. Many thanks