10 Essential Manhattan Albums

Welcome back to the Treble World Tour, a series of Top 10s covering albums that best represent certain locations—cities, states, territories, even entire nations. We consider representative releases on three levels: They were made by artists from a place, they contain music about or inspired by the place, and/or they were made in that place. When we started these articles, we knew that some locales could generate lists much bigger than a Top 10 given the chance. We’ve debated when and how to codify and quantify scenes like London and Los Angeles, with their overpowering tapestries of musical influence.

Tackling New York CIty as we’re about to is no small feat, but our particular bite of the Big Apple comes from what we think is a new direction: We’re centering our collected opinions of the city’s greatest music on each of its five boroughs. Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island, Brooklyn, and The Bronx each contain their own set of unique characters and communities. The five then combine again to give New York City a globally accepted image of constant activity that uses camaraderie and conflict, pleasure and strife in equal measure to motivate its residents and inspire its artists.

This week, Treble begins our series-within-a-series looking at 10 albums that sum up the Manhattan experience. New York City is The City That Never Sleeps because this central borough is its beating heart—hub of important industries, home to impossible extremes of success and failure, and host to countless visitors and tastemakers. When you think of this megacity, you probably think of Manhattan’s skyscraper-sculpted canyons with endless streams of traffic, the dichotomy of Central Park wealth and park-bench homelessness, and a soundtrack pretty much everywhere from Broadway to the Bowery to the back of your cab.

Much of what was ever “pop” in America was likely so because it was popular in Manhattan first, and we’re not just talking about content pushed by today’s radio, labels, or streaming services. Gotham started out ably serving the mainstream with the music of theaters and orchestras, Brill Building songwriting, and Radio City Music Hall. It then grew to include the countercultural sounds blaring out of jazz clubs, Greenwich Village, warehouse parties, and modern Madison Square Garden. Downtown New York has probably lost and forgotten more music than most other individual scenes have generated, and Treble easily could have paid homage by acknowledging 50 or even 100 great albums about Manhattan. For now, these 10 will have to do, and we’ll see you back here next week for the music of borough number two.

Various Artists – West Side Story: Original Soundtrack

Various Artists – West Side Story: Original Soundtrack

(1961; Columbia)

This album represents so many of Manhattan’s creative strengths as they developed through the first half of the 20th century. A quartet of national performing arts legends who just happened to be New Yorkers—choreographer Jerome Robbins, songwriter Stephen Sondheim, playwright Arthur Laurents, and symphonic conductor Leonard Bernstein—spent a decade working to update Shakespearean tragedy against a backdrop woven from classical, pop, Latin dance, and eventually a little rock and jazz. The results set a then-stagnant Broadway on its ear and launched probably half a dozen songs (“Tonight” and “Somewhere” among them) into public consciousness. The original 1957 cast recording is beloved in its own right, but the 1961 film soundtrack is part of a landmark United Artists production that won 10 Oscars including Best Picture and Best Score. A poignant, politically pointed tale of love that blooms amid violent youth and racial division, if West Side Story doesn’t take its chances who knows if there’s a Jesus Christ Superstar, a Rent, or a Hamilton to follow suit. – Adam Blyweiss

Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

(1963; Columbia)

Bob Dylan and Suze Rotolo are seen taking a stroll on a what would appear to be a frigid day on 4th Street in Manhattan’s West Village, immediately giving Dylan’s second studio album a sense of place. And indeed, the album itself helped to establish Dylan and by extension the Greenwich Village folk scene from which he came to a broader American audience. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is a crucial recording in popular music on the whole, a meeting place between folk tradition, pop songwriting and protest music that brought topics such as nuclear disarmament, civil rights and the military industrial complex to a wide audience. In a sense, Dylan was inviting the rest of the world into one of his more intimate coffeehouse performances in the village, wherein he’d deliver an ominous protest song (“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”), a break-up song of whimsy and playful phrasing (“Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright”), surrealist streams of consciousness (“Bob Dylan’s Dream”) and even some traditional folk tunes (“Corrina, Corrina”). The album’s a snapshot of Bohemian Manhattan that will never exist in the same way again, other than in the recreations of the cover photo that even today’s hipsters will inevitably Instagram. But it’s forever captured in this folk masterpiece by a kid from Duluth, Minnesota. – Jeff Terich

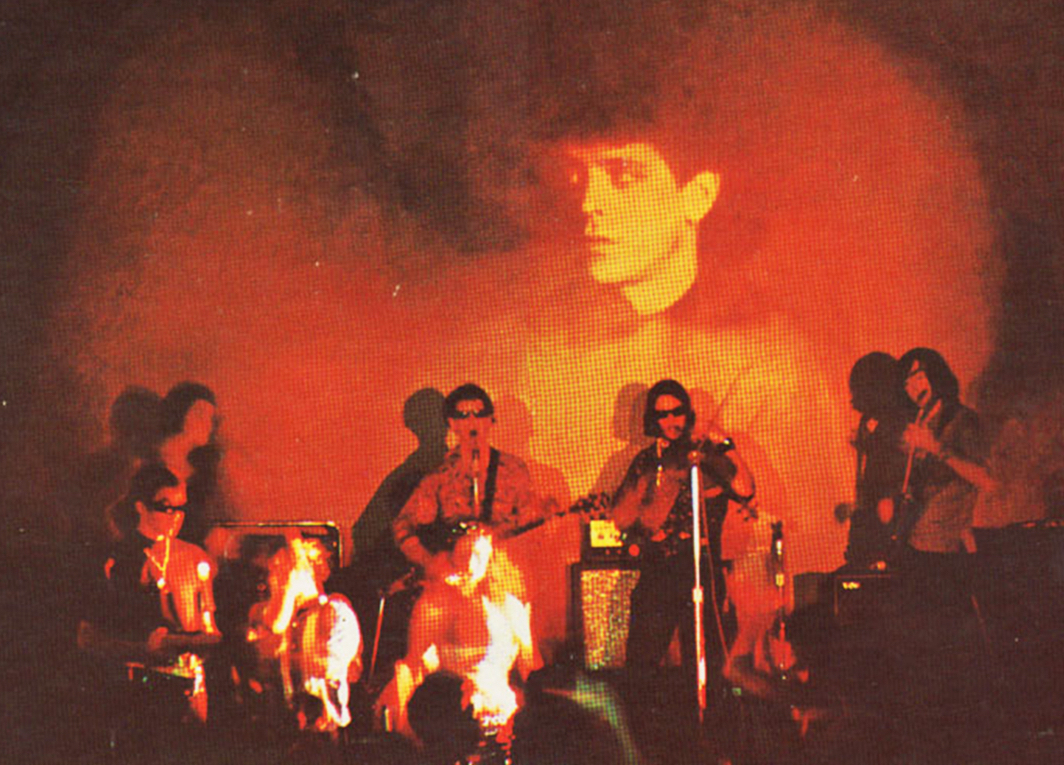

The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground & Nico

The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground & Nico

(1967; Verve)

Hip before hipsters were a cliche, punk before punk was punk, and famous for having been something of a well-kept secret upon its release, The Velvet Underground’s iconic debut is counter-cultural New York City in 11 wild, psychedelic tracks. Managed, promoted and produced by none other than Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground were, themselves, a subversive artistic act. Recorded in both Manhattan and Hollywood, The Velvet Underground & Nico took a dark and seedy route through the less glamorous corners of Manhattan in the late ’60s. Heroin, sadomasochism, prostitution and other taboo topics at the time were fair game for songwriter Lou Reed, and their raw sound was a major reference point for the punk sound to come in the ’70s—not far from where the Velvets themselves were performing. The oft-repeated saw about the album is that nobody heard it when it came out, but everyone who did formed a band. More than likely they also did something weird, wild and fucked up, much like the junkies, hustlers and weirdos that populated the New York City that The Velvet Underground knew. This ain’t the summer of love. – Jeff Terich

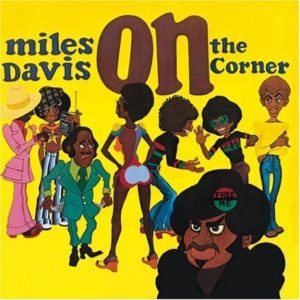

Miles Davis – On the Corner

Miles Davis – On the Corner

(1972; Columbia)

Manhattan for much of the 20th century was the epicenter of jazz in the United States—from Midtown’s Birdland to Greenwich Village’s Village Vanguard to Columbia Studios, where many of Miles Davis’ records were captured on tape including this one right here. And one could point to any number of Davis’ records as being emblematic of how significant a locale New York City was for jazz, including his 1959 masterpiece Kind of Blue. But On the Corner is also an example of how significant New York was in upsetting the balance. By the early ’70s, Davis was tired of the conservatism (and whiteness) of jazz and explicitly sought to make an album that resonated with a Black audience—including the Blaxploitation-like “ghettodelic” artwork on the cover from Corky McCoy, with whom Davis shared an apartment on West 77th Street. As such it has a lot more in common with funk and R&B music of the ’70s, albeit filtered through the experimental lens of Karlheinz Stockhausen. It’s a peculiar album, one that’s not quite jazz but definitely not pop, but certainly off-kilter enough to aggravate both jazz critics and his label. It’s funky, agitated and intense—like Manhattan on a July afternoon. – Jeff Terich

Billy Joel – Turnstiles

Billy Joel – Turnstiles

(1976; Columbia)

Look. Nobody’s going to confuse the urban observations of the top-selling New York artist of all time with Lou Reed’s. Frequently chastised for shooting way above his rank, Billy Joel’s depictions of the kingdom of Manhattan were more like telescopic impressions from the relative safety of Long Island, more spunk than grit. But come on: Somebody had to decipher NYC for the suburbs, didn’t they? Leave the Velvets, the Dolls and Television for those with more fortified gizzards—Billy Joel cleaned up the Windex spill in Aisle 4 like nobody’s goddamn business. Besides, his last album before superstardom is his steadiest, most New York album, and four of its eight songs are among his best ever. “Say Goodbye to Hollywood” places Joel’s real-life exodus from L.A. in a properly Spector-ian context. “Miami 2017” is a fun, propulsive what-if about the apocalyptic desecration of New York landmarks from the point of view of Florida retirees. “New York State of Mind” may be an easy lay-in, but it remains a sturdy and moving torch song. And if you interpret “Summer, Highland Falls” as satire (cross your fingers, hard), it’s an effective and effete take-down of upper-middle-class navel-gazers who got at least halfway through the self-help books of the ‘70s. As for the rest of the songs… well, one of them’s a “reggae” number. – Paul Pearson

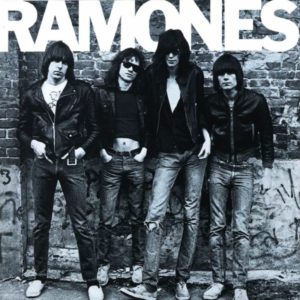

The Ramones – Ramones

The Ramones – Ramones

(1976; Sire)

If you must put an above-ground pin on the historical map of New York’s musical underground, then let it be at CBGB, the music venue dearly departed from Manhattan’s East Village. And if that site must be represented by one band, then for the love of all that is unholy let it be The Ramones. While they may have formed in Queens, the First Foster Family of Punk used CBGB and other crummy Manhattan venues to hone to fine points their minimal chord progressions and brief tales of disaffected youth. Their first statement, in the form of their self-titled debut LP, may have been their loudest and best, as well as the most representative of a nascent genre. Joey Ramone’s vaguely melodic chants—often cowritten with bassist Dee Dee—were matter-of-fact observations of evil and sadness seen in news of the day (“Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue”), personal relationships (“I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend”), others’ escapist art (“I Don’t Wanna Go Down to the Basement”), and even Nazism (“Blitzkrieg Bop”). Powered by Tommy Ramone’s oompah drumming and Johnny Ramone’s tense guitar, it’s an album and style flying by at hyperspeed, 14 songs covering 43 years of ground—and counting—in 29 minutes. – Adam Blyweiss

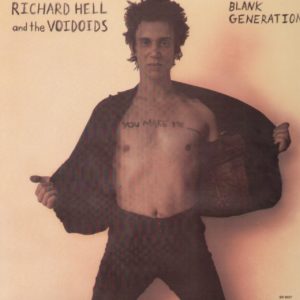

Richard Hell and the Voidoids – Blank Generation

Richard Hell and the Voidoids – Blank Generation

(1977; Sire)

Kentucky-born poet turned punk auteur Richard Hell ironically assisted in defining New York’s punk identity. But it was Blank Generation that solidified an avant garde sensibility. The title track is the most recognizable song from the album, and it’s masterful, ripping with a dark groove and bassline. Found throughout the album is a flirtatious sonic depth, and charges of crude but effective guitar tones and progressions. “Love Comes in Spurts” is one of the best openers on any punk album ever. But the musicality here isn’t as important as the attitude, equally irreverent, vicious and influenced by French poetry as it was Richard’s own contemporaries. There’s a nuance beneath the grime and the grit, exemplified by its closer “Another World” with its daunting complexity and sheer scope that belies the rest of the album’s loud fast and nasty concepts. – Brian Roesler

Talking Heads – Fear of Music

Talking Heads – Fear of Music

(1979; Sire)

Anything, and I mean anything that David Byrne and Brian Eno worked on is solid gold. But in terms of embodying the culture, sound, and sense of place at the time of recording, Fear of Music shares in interesting history of multiple locales, but finds its soul in New York City. And friends, what a soul it is. Groovy, layered with complex harmonies and utterly smooth yet still temperamental rhythms, Fear of Music was and remains at its core utterly playful. You could pull any song off of here and let it stand righteously on its own as a towering monument to the band’s sonic abilities (“Life During Wartime” even makes the NYC connection explicit: “This ain’t no Mudd Club, or CBGBs“), but it’s “Heaven” that feels the most complete, channeling the band’s next efforts in Remain in Light while remaining a transcendentalist urban ode. FOM is a stout-hearted and soundscape-driven affair, and one that must be heard to understand the aural cosmology of Talking Heads. – Brian Roesler

Tom Waits – Rain Dogs

Tom Waits – Rain Dogs

(1985; Island)

If one were to ask what album would serve as the best entry point to Tom Waits, I would point them to this 1985 classic. Waits’ 8th album features songs loosely tied to the theme of dispossessed street people of New York—along with locations referenced, like “Midtown” and “Union Square”—straddling the line between experimental urban pirate shanties and more bluesy mainstream song, including his biggest hit “Downtown Train.” Despite being in the middle of trilogy sandwiched between Swordfishtrombones and Frank’s Wild Years this album stands on its own two feet, not to mention being graced by the guitar talents of both Keith Richards and Marc Ribot. Not his first foray into the back alley bar room ballads, Tom Waits’ songs on this album are more refined, with tracks like “Jockey Full of Bourbon” blending in Cuban grooves to dramatically employing New Orleans funeral jazz found in other songs. It was on this album his days playing in smokey dives that his voice settled into the raspy baritone Waits is known for. His voice cracks as he reaches for notes that are filled with honest emotion, even when he is playing a character.- Wil Lewellyn

LCD Soundsystem – Sound of Silver

LCD Soundsystem – Sound of Silver

(2007; DFA/Capitol/EMI)

At the turn of the new century, Manhattan was home to stalwart providers of indie rock (The Strokes, Interpol) and the genre’s dance-punk offshoot (The Rapture, Le Tigre). Yet with so much street cred to go around, there was exactly one artist who could nimbly hop from the broad and the specific in this musical manner. That was DFA producer and LCD Soundsystem bandleader James Murphy, as comfortable remixing New French Touch techno and David Bowie as he was directing his bandmates to mimic them. But Murphy was more than just a gadfly for Manhattan’s gentrification set, and it showed in the creative leaps LCD Soundsystem took between their self-titled debut and Sound of Silver. It stands as a simultaneous defense and critique of millennial culture, handed down by Generation X’s Warhol with a dad bod. Always a keen observer of the scene he nurtured, Murphy moved the band away from their old hootenanny of No Wave-meets-rave to extend and make supple every new groove (“Get Innocuous,” “Us v Them”). Given two years to mature, their funk and Krautrock echoes (“All My Friends,” “Sound of Silver”) were exponentially more emotive and engaging. And for an art form—and city—averse to acknowledging the psychological spectres of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, to have these party-rockers (of all people!) powerfully acknowledge personal loss in “Someone Great” and safe, sterile society in “New York, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down” is a miracle inside a miracle. – AB

Various Artists – West Side Story: Original Soundtrack

Various Artists – West Side Story: Original Soundtrack Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground & Nico

The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground & Nico Miles Davis – On the Corner

Miles Davis – On the Corner Billy Joel – Turnstiles

Billy Joel – Turnstiles The Ramones – Ramones

The Ramones – Ramones Richard Hell and the Voidoids – Blank Generation

Richard Hell and the Voidoids – Blank Generation Talking Heads – Fear of Music

Talking Heads – Fear of Music Tom Waits – Rain Dogs

Tom Waits – Rain Dogs LCD Soundsystem – Sound of Silver

LCD Soundsystem – Sound of Silver

How can you have a list of Manhatten albums without Eat to the Beat.