10 Essential Next-Level Albums

Every artist undergoes some kind of change throughout their career. Some peak early and end up spending years trying to recapture the thing that they initially found so easily. Others undergo a steady period of growth for years, even decades. And some spend years away from the studio entirely, only periodically emerging to deliver something fascinating. But pop music history is littered with albums by artists who level up—that moment where they graduate to a higher grade or progress to a new stage. As a new year lies ahead of us, full of promise for new and exciting things, let’s take a look back at the albums that marked the point at which some of our favorite artists ascended.

Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon

Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon

(1973; Harvest)

There were earworm riffs and easy-to-process ideas in Pink Floyd’s catalog up to and including 1971’s Meddle, but you had to slash through deep auditory jungle to find them. The longest journeys sometimes begin with the simplest step, and the band’s decision to cut back on the musical wankery for their next album turned out to be a legendary one, with new songs at manageable lengths and clear lyrics around themes of life’s struggles. In what might be a bold move today, they also demoed and then toured behind the music that would become The Dark Side of the Moon before finishing it off in the studio. Honing their psychedelia to a laser-sharp focus ended up benefiting the pop charts, stadium audiences, and ultimately music history. – AB

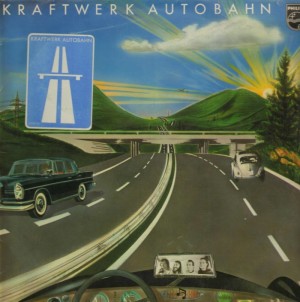

Kraftwerk – Autobahn

Kraftwerk – Autobahn

(1974; Philips)

It took some time before Ralf and Florian made their way aboard the Trans-Europe Express. The earliest records by Kraftwerk didn’t employ the proto-synth-pop textures and songwriting that made them groundbreaking in the mid- and late-’70s, but rather the kind of instrumental abstraction that their peers in Neu! likewise took on. Even their early album covers look similarly minimalistic. But then Autobahn happened, and with it an embrace of melody and hooks that eventually found them redefining what pop is and could be. As expansive as the title track is, and for as much progress as Kraftwerk made with this record, they still had plenty of other destinations to reach along their motorik journey. – JT

New Order – Power, Corruption & Lies

New Order – Power, Corruption & Lies

(1983; Factory/Qwest)

New Order’s debut album, Movement, isn’t a bad album. It’s not a disappointing album. It’s not even an underwhelming album. But at the time of its release, New Order were just a year removed from being Joy Division, still grieving for their late singer and uncertain of how to move forward from the band that they were. So while there were plenty of excellent songs (the post-punk jangle of “Dreams Never End,” the dance-goth of “Chosen Time”), the shadow of Joy Division still loomed heavy over their creation. Two years later, New Order emerged from their darkened chrysalis a new band, one that shook off the identity crisis and embraced electronic sounds anew, along with a crisper, brighter sound informed by the likes of Kraftwerk as well as employing a melodic sensibility that out-popped anything they had previously released (Peter Hook still cites “Age of Consent” as one of the best basslines he ever wrote, and it’s hard to disagree). To situate Power, Corruption & Lies as a grand turning point for the band might be to overlook significant singles such as “Temptation” and “Everything’s Gone Green,” but this is the moment where those bursts of inspiration came together as one bigger, fully-realized statement. – JT

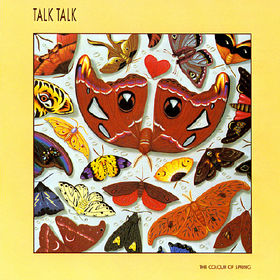

Talk Talk – The Colour of Spring

Talk Talk – The Colour of Spring

(1986; Chrysalis)

Talk Talk seemingly became a different band with each album they released, undergoing a dramatic metamorphosis from catchy, commercial synth-pop in the early ’80s to pioneers of post-rock by the time they disbanded. The pivotal moment in their transformation came at exactly the midway point, however, when synths and drum machines no longer had a central role in their songwriting, and their ideas were no longer hemmed in by the dictates of radio or MTV. The Colour of Spring isn’t their most radical statement, though it wasn’t that far behind. Rather it was the moment where exploration outpaced immediacy, and where the idea of what the band could be was no longer limited by perceptions of what the band had been in the past. The list of personnel on the album is vastly longer than on past records, and the range of sounds far more expansive. Also, for some reason, Steve Winwood plays organ on the album. Talk Talk had a lot more to say, and vastly more ways to say it—and after its release, not much need to have to play those ideas live. Though even those who heard this upon its release couldn’t have predicted the radical turns of Spirit of Eden or Laughing Stock. Those simply couldn’t have happened without this coming first. – JT

My Bloody Valentine – Isn’t Anything

My Bloody Valentine – Isn’t Anything

(1988; Creation/Sire)

My Bloody Valentine as they initially sounded on the series of EPs released in the first few years of their career are essentially unrecognizable as the band we know now as shoegaze pioneers. Their sound evolved from a Cramps-like psychobilly post-punk into a fuzzy twee-pop and eventually a better realized dream pop on 1987’s Strawberry Wine. But the following year’s Isn’t Anything, their full-length debut, not only found My Bloody Valentine completely rebranded but newly inspired as well. Though still a distance from the sonic onslaught of their 1991 masterpiece Loveless, Isn’t Anything is My Bloody Valentine fully coming into their own and delivering the first proper document of their incredible sound and vision. Though some of that came with the release of the “You Made Me Realise” single, Isn’t Anything took that idea and blew it wide open, sharpening up their distortion, filling out their sound and out-psyching any of their proto-shoegaze peers. There was still plenty of room for growth, but Isn’t Anything proved what they were made of. – JT

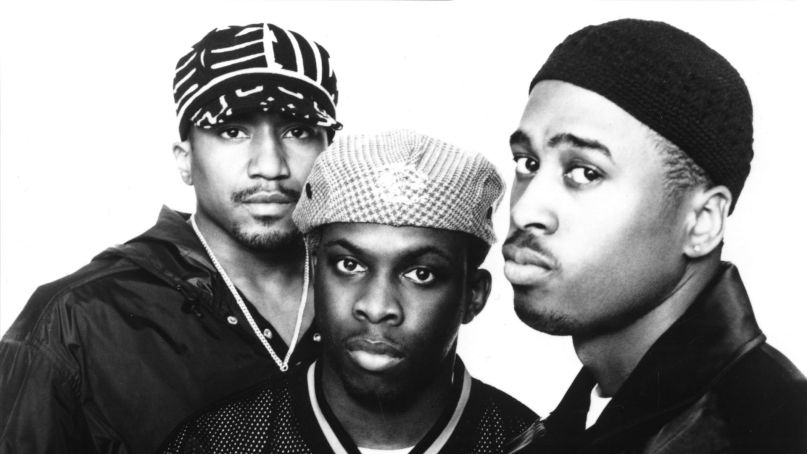

A Tribe Called Quest – The Low End Theory

A Tribe Called Quest – The Low End Theory

(1991; Jive)

Dripping with complex jazz modal vibes, unparalleled head-nod energy, and lyrical Afrocentric unity, The Low End Theory propelled hip-hop and the sampled music industry from rudimentary sonic dimensions to 5k digital blast. Produced by Q-Tip with help from Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the album set a new precedent for deep resonating sound compression by double and tripling bass noises and samples. This was such a radical, specific aesthetic, that within 48 min ATCQ snatched both the ears of the culture and the mainstream, without compromise.

It’s a perfect album. There is not one moment to fast-forward through. The 14 songs whizz by with punk-rock brevity. As a sophomore follow-up, it ranks just above Paul’s Boutique by The Beastie Boys and just below De La Soul’s De La Soul is Dead. Bob Power, the album’s engineer who manufactured a prodigious career primarily from the merits bestowed here, always referred to The Low End Theory as “The Sgt. Pepper’s of Hip-Hop.” The one-two punch of Q-Tip and Phife Dawg on the mic, pushing each other to perfection by fulfilling the roles of opposites, laid out the formula that André 3000 and Big Boi would eventually play in OutKast. “Butter” let everyone know that Phife Dawg was definitely here to pull his own weight, not merely a second banana. Yet Q-Tip rightly shouts out his generation of contemporaries, giving mic time to the Native Tongues, introducing the very skillful bass work of Jazz musician Ron Carter to the future generations. Along with providing Busta Rhymes space to dispatch iconic fire bars during the climactic final dart “Scenario,” the LP illuminates the point that movements don’t happen just by one entity. It takes a symphony of voices to amplify a message. Establish a rhythm. – JPS

Nine Inch Nails – The Downward Spiral

Nine Inch Nails – The Downward Spiral

(1994; Nothing/Interscope)

Several entries in this countdown find artists making the leap from merely composing songs to crafting worlds and stories. The shift in tone between Trent Reznor’s first three releases and The Downward Spiral was a seismic one—and that’s saying something, considering how aggressive Nine Inch Nails sounded right out of the gate. Pretty Hate Machine, the Broken EP, and the Fixed remix compilation had each been assembled catch-as-catch-can whenever Reznor had time, space, and help. Once Reznor was clear of his TVT Records contract, he was free (and financed) to address the old monsters and new demons in his life. The result was a swirling yet cohesive reshaping of the industrial-music tropes he had promoted to that point, where every salve could sting, every joy could lead to isolation, every escape brought peril. – AB

The Pharcyde – Labcabincalifornia

The Pharcyde – Labcabincalifornia

(1995; Delicious Vinyl)

Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde is a frenetic, humble and, affectionately speaking, juvenile opus out of LA’s freestyle-centric era of the early ’90s. And as freestyle raps often go, the record is full of dirty limericks, yo-momma jokes and plenty of lusty banter. Bizarre Ride is also unique in that the group regularly muses on amorous daydreams (“Passing Me By”) and mending broken hearts (“Otha Fish”). Three years later, the group dropped Labcabincalifornia which still deploys the group’s bouncy flow and self-depreciating humor. However, the group’s second album uses more harmonious melodies—“She Said” and “Runnin’” hear the group acquiesce on notions of romance and masculinity and craftily intertwine soulful croons with their whimsical bars. – PG

Radiohead – The Bends

Radiohead – The Bends

(1995; Capitol)

Radiohead is a little like Talk Talk in that each release up to 2000’s Kid A was indeed a leveling up. But this one was the most important. Still a rock album, and arguably even the band’s only Britpop album, The Bends saw beyond the one-hit wonder status of “Creep” and opened the doors to experimentation, textural development, and an overall pursuit of bigger ideas that came to be Radiohead’s stock in trade. By the psychedelic echo of opener “Planet Telex,” Radiohead signaled that they were no longer playing by the same rules, and while they somehow managed to retain the support of commercial radio, they also began to dare program directors to take bigger chances. In the case of “Fake Plastic Trees,” itself an atmospheric ballad inspired by a newcomer named Jeff Buckley, it worked. (The spacey post-punk of “My Iron Lung,” not as much.) And while by the band’s current standards there’s nothing particularly weird about this album, it transformed Radiohead from short-term attention grabbers to a band in search of something much bigger. – JT

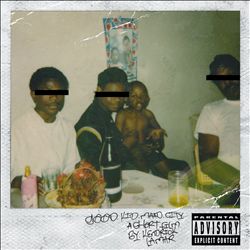

Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city

Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city

(2012; Top Dawg/Aftermath/Interscope)

Kendrick Lamar made a pretty strong debut with 2011’s section.80, so it’s not like the epic breakthrough of the next year’s good kid, m.A.A.d. city was necessarily a total surprise. It was, however, such a dramatic leap forward that the compton emcee went from promising up-and-comer to MVP seemingly overnight. The scope of the album has a lot to do with that—in 12 tracks, Lamar stitches together a narrative that somehow encompasses both a single night and an entire lifetime, a younger version of Kendrick stunting on “Backseat Freestyle” and dealing with peer pressure throughout, while an older, more pessimistic version of himself ponders his legacy on the sprawling “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” This isn’t just a better album than its very good predecessor, but a leap from undergrad to Ph.D. candidate, with bigger stakes and bigger statements. One might claim that there are better or more important artists in hip-hop right now, but good kid, m.A.A.d. city began a long series of arguments to the contrary. – JT

Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon

Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon Kraftwerk – Autobahn

Kraftwerk – Autobahn New Order – Power, Corruption & Lies

New Order – Power, Corruption & Lies Talk Talk – The Colour of Spring

Talk Talk – The Colour of Spring My Bloody Valentine – Isn’t Anything

My Bloody Valentine – Isn’t Anything A Tribe Called Quest – The Low End Theory

A Tribe Called Quest – The Low End Theory Nine Inch Nails – The Downward Spiral

Nine Inch Nails – The Downward Spiral The Pharcyde – Labcabincalifornia

The Pharcyde – Labcabincalifornia Radiohead – The Bends

Radiohead – The Bends Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city

Kendrick Lamar – good kid, m.A.A.d. city