In the absence of facts, a myth can take shape. And the overarching myth of My Bloody Valentine formed precisely because of various periods of extended absence, the likes of which have reverberated loudly throughout their career. In the early ’90s, after the release of their critically acclaimed second album, an apocryphal narrative emerge of genius brought to the point of fracture—that they had nearly bankrupted their label in the process of recording a single album, that they had a meltdown in its aftermath, that bandleader Kevin Shields became a reclusive perfectionist a la Brian Wilson, and that nothing he or the band created was ever going to be good enough to make the tracklist of their next album. All of which is true—to varying degrees anyway. And it’s all because of Loveless.

For nearly two decades, their longest period of absence spoke louder than the band’s own exquisite noise. The slightest hint of a My Bloody Valentine appearance—recording a Wire cover for a tribute album, Shields’ appearance on Primal Scream’s XTRMNTR and subsequent work on the soundtrack for Lost In Translation—seemed ripe for speculation and interpretation. But the years tumbled on and the group offered no whisper of anything resembling new music or even a live performance for well over a decade. The group did few interviews in that time, and even most of the photos of the band on the Internet now date back to the Loveless press campaign. But they never intended to disappear; quite the contrary, new music was seemingly always just around the corner.

As early as 1997, Shields seemed to feel the pressure of that absence, explaining in an AOL chat for the Cool Beans! zine that the band would be be releasing music “Definitely sometime this year or I’m dead…”, clarifying that the only pressure on him for releasing music was self-directed.

An album like Loveless will do that. No point in understating the matter: It’s perfect. But more than that, it’s an ideal—of what? Pretty much anything you got. It’s the album against which all other shoegaze albums are compared (along with Slowdive’s Souvlaki and to a lesser extent Ride’s Nowhere) but which has no equal. It’s the most stunning guitar album of the ’90s alt-rock era, cresting just as grunge took over but employing distorted crunch in more alien and elegant ways. (Notably, it was also a major-label stateside release before Nirvana’s Nevermind sent the industry into an underground rock signing frenzy.) It’s also a prime example of the fluid possibilities of fusing rock music with electronic elements, employing samples, drum loops and the dancefloor mania of acid house under the guise of ostensibly being an album made by a rock band. More or less.

Nothing sounded like Loveless at the time, and despite a thousand Tik Tok-approved bands’ attempts to make their own, they all fall short, fixated on the aesthetic rather than the ineffability of it all. When you hear Loveless for the first time, you’re likely to conjure up a few myths of your own about the kind of devices and strange studio mechanics required to make music that sounds like this, and you’re just as likely—as I did sometime around fall of 1999—to find yourself at a loss for words for what precisely makes this music so enchanting.

It doesn’t necessarily take much deep thought to pinpoint why the heavy-riffing opener “Only Shallow” provokes such a surge of adrenaline, or for that matter why the dance-gaze BPMs of closer “Soon” compels corporeal movement. But the distance between these two endpoints is one of endless drift—or rather “glide,” the term that Shields himself coined to describe his technique for playing guitar with liberal use of a tremolo bar on a Fender Jaguar or Jazzmaster (hence the titles of the album’s two preceding EPs, Tremolo and Glide). The effect is one of endless movement and a feeling of never fully resolved depth, as if you could reach through one layer after another and find that there’s always another one just behind it. It’s strange and beautiful, and sometimes unknowable—to actually understand the words that Bilinda Butcher is singing threatens to undo the spell they cast, intoxicatingly beautiful in their indecipherability.

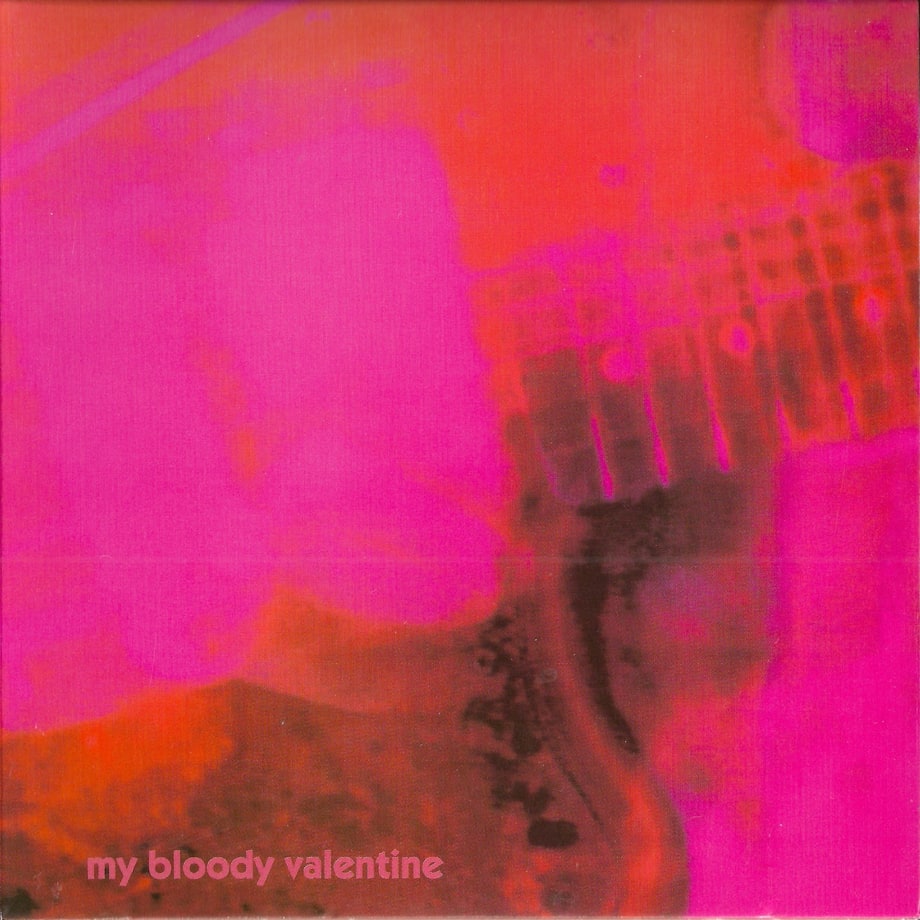

The same logic doesn’t quite apply to the album itself, a work of sonic sorcery made all the more remarkable through the transparency of how it was crafted. The enveloping richness of Loveless suggests an army of guitars that look as shapeless and blurred as the one on the cover, but Shields said it actually features “less guitar tracks than most people’s demo tapes have.” The same goes for the effects chains, which are almost shockingly minimal, the guitar tracks recorded in mono with most of their otherworldly effects happening as a result of Shields’ signature glide techniques. Creation Records believed the album could be recorded in five days, but the finished product—recorded and meticulously pieced together almost entirely by Shields himself, which was more feasible than trying to translate the sound he heard in his head to his bandmates—took two years. Despite the instrumental tracks coming together relatively quickly, nearly a year lapsed before Shields and Butcher finished the lyrics, and they cycled through about a half-dozen studios in the process, the final product—which became an increasing source of stress for Creation Records—was estimated to have cost £250,000. Shields suggests that number’s likely a bit lower, though nobody in the band had kept track.

As much of a headache as it might have been behind the scenes, and however straightforward the actual methods of making it (despite the mountain of studio fees), Loveless still feels like magic. Which seems almost like an impossibility; after all, once you learn the trick, the illusion is shattered. The same can’t be said of Loveless, which feels all the more remarkable given that it was created from human hands and voices, audio tape, wood and steel. In 30-plus years of technological advances, it hasn’t been improved upon, other than perhaps through Shields’ own remaster. It’s an album that’s meant to be played loud and with minimal distractions—a good pair of headphones or speakers will do, though Shields can vouch for it sounding good enough through his phone speaker.

For as much attention is given to the dense, overwhelming sound of it all, Loveless is ultimately a set of pop songs made hazier and perhaps intangible—if no less immediate. “To Here Knows When” is an ascent to heaven through an undefined vessel, where as “Loomer” has a sinister drive behind it yet bleeds at the edges, free of a grounding pulse. “When You Sleep” is one of the few moments that actually sounds like a proper rock band hammering it out in the studio, whereas “Sometimes” is the shoegaze equivalent of a lullaby, a warm blanket of fuzz and arguably the album’s prettiest song. To say nothing of the energetic fury of “Only Shallow” and the battery-acid-house of “Soon.”

These songs seem to change and grow with the listener, the utmost example of the album that reveals something new with each listen. Loveless has the distinction of being the only album I’ve bought four times: two different formats, a remaster and a replacement after an unfortunate mishap. I’ve heard it hundreds of times but never shake that sense of mystery, its secrets never fully revealed, its charms seemingly limitless. I don’t know if there’s any album I’ve listened to as consistently over the past 25 years without having shaken that sense of wonder.

Despite the consternation and heartburn caused during the album’s creation, Shields himself recognizes that the end result was still very much worth it. “I know why I did everything. It couldn’t be done differently,” Shields told Pitchfork in 2017. “Without getting pretentious, it’s a bit like I made a painting and I just got it right. I achieved what I was trying to achieve at the time.”

My Bloody Valentine did, 16 years after that AOL chat, release a new album, 2013’s mbv. And by the time it arrived, music itself had undergone tectonic shifts—creatively, economically, technologically. As listeners we consumed music differently, and artists made records in much different ways than My Bloody Valentine’s peers had in the early ’90s. That itself might have tarnished some of the magic by the time the group finally got around to delivering their third album, though it didn’t diminish what was ultimately a phenomenal set of music. It also didn’t prevent the group’s website from crashing due to so many users attempting to download the album at once.

More than anything, it felt miraculous that it materialized at all. But then again, so does Loveless

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.