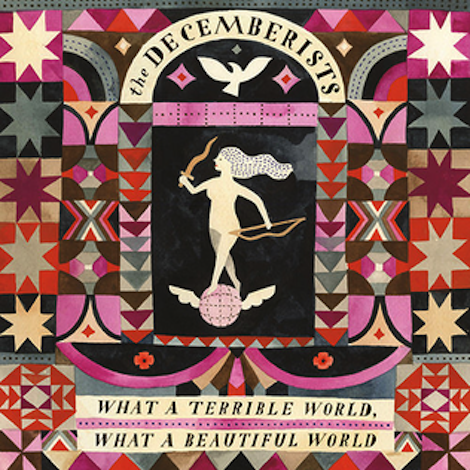

The Decemberists : What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World

Hold that thought, because the new Decemberists album starts off with a disclaimer. On their first album in four years — seventh overall — Colin Meloy starts off with “The Singer Addresses His Audience,” a droll bit of mock self-importance and mock self-deprecation that probably every other artist in music wishes they could make if only it didn’t hold up your getting to the single which is probably on track 3 or so.

It makes total sense for an artist to say what Meloy says to his adoring fans in this chutzpah-replete overture: “We know you built your life around us / Would we change? We had to change some.” Nobody wants their favorite rock bands to grow up, despite the near-inevitability that unless the plane crashes or the narcotics do their jobs too well, they will. Maybe they’ll sell out. Maybe their traditional revenue streams will dry up and they’re going to have to license their songs to advertising concerns (as Meloy presupposes, “Axe Shampoo”). Or maybe they’ll just grow older and have families, which some of us might consider an onerous burden of distraction to our poetry-writing and annual sojourns to Burning Man, at which point we’ll accuse The Decemberists of one of two equally terrible things: growing up or getting old.

“The Singer,” pre-emptive, Kanye-esque strike that it is, feels disingenuous and coddling, as “meta” as the Portlandia from whence it came. But that may be intended. Could it be necessary? Meloy is all too aware of the rickety construct between artist and audience, how much of that bond relies on the preservation of youth, even if it’s fantasizing about maturity. So when Meloy sings “We had to change some / You know… to belong to you,” the decision is yours as to whether such self-sacrifice is altruism or complete bullshit. I’ll bet you it’s a little of both, because these things usually are.

And its functionality is questionable, because the rest of What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World finds only a few noticeable deviations from the Decemberists’ ongoing aesthetic concerns, and a very slight shift what they say. Meloy is a mythologist — both of himself and ecology — who’s gotten away with it because he’s never really taken himself, as a present entity, too seriously. For that reason one’s likely to forgive this album’s lack of conclusions, because it’s all about the children, who are by definition a long way from finding conclusions.

The songs that immediately follow the disclaimer are similar to the boldness of sound R.E.M. suddenly captured with Green. They harken to the development of self and sensuality in youth, or at least of not-that-long-ago. “Cavalry Captain” is a brazen warrior, either unaware or gleefully ignorant of his ulterior motives (“I am the remedy to your heart!”) in his pursuit to be your spirit animal (or at least your Tennyson). “Philomena,” a jaunty and jangling recollection of the Chills’ “Heavenly Pop Hit,” is Meloy’s most plainspoken expression of lust, with a promise that’s both surprising in its explicitness yet oh, so Decemberistic in its placement: “I’ll be your lash and loop of leather and dark / Philomena, if only you’ll let me go down, down, down.” “Make You Better” is the kind of uncomfortable net ambivalence that dwells within the spirit of a lot of The Decemberists’ work, and it’s a truly resonant portrait of the fluctuations of power and dependence in a relationship: “We’re not so starry-eyed anymore / Like the perfect paramour you were in your letters.”

The album’s middle is a breeze through recollection and fixations that either evoke bittersweet comfort or halted trepidation, if that isn’t redundant. The folk restraint of “’Till the Water Is All Long Gone” and “Carolina Low” gives fitting gothic backdrop to accounts of mysterious events. A shift happens in the brief “Better Not Wake the Baby,” an almost trivial send-off to the confused rage of youth amongst reformed priorities (“You can bang a drum ‘til the money’s gone / But it better not wake the baby”). Here’s where the songs and the details get sparer, and Meloy almost seems like he’s brushing off an assumed identity. “Anti-Summersong” is reflective and sarcastic (“Don’t everybody fall all over themselves”), and the blunted surf-guitar of “Easy Come, Easy Go” accompanies an almost blasé approach to change and, we think, death (“He was a stand-up gent, but no one knew his bent / And all the little bones that he hid in his vent”).

Terrible World ends in a couplet of songs that bring the themes of childhood, loss and self-regeneration into plain view; by merit of their position they’re the most evocative statements on the album. “12-17-12” is a plaintive, sincere love song to a child born in the midst of chaos that seems like common acceptance of what we already know, until you realize that the date in the title was when the Sandy Hook shootings took place. Meloy’s measured passion then strikes at a much deeper level. “A Beginning Song” ends in grandiose ecstasy, with lines that could be coming from either a parent or the baby that’s just showing up (“If I am waiting, should I be waiting? If I am wanting, should I be wanting?”) while the very rough outlines of what seem to be wonder come into view.

The Decemberists are appreciably restless in their musical approach, as they should properly be. Guitarist Chris Funk finds some newly aggressive angles in “Easy Come, Easy Go” and “A Beginning Song” that don’t trespass the established Decemberist plotline, and the embrace of acoustic styles is pushed slightly towards the middle a bit more than before. “Anti-Summersong” is perilously close to the good kind of contemporary country that exists today.

What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World sounds, on the surface, like the Decemberists’ treatise on the compromise of maturity and the settlement of the world’s dual natures of destruction and wonder, and what it lacks in finality and expressive emotional truths it probably makes up for in discussion starting. The more you get into it, the more superfluous that opening disclaimer seems. It’s Colin Meloy’s re-entry from myth into storytelling, if that makes any sense. If it doesn’t now, it might when you’re older.

Similar Albums:

R.E.M. – Green

R.E.M. – Green

Belle and Sebastian – Write About Love

Belle and Sebastian – Write About Love

Okkervil River – The Silver Gymnasium

Okkervil River – The Silver Gymnasium

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.