Hall of Fame: David Bowie’s Station to Station

“I’m all through with rock & roll. Finished. I’ve rocked my roll. It was great fun while it lasted but I won’t do it again.”- David Bowie in a Rolling Stone interview, February 12, 1976.

A month has drifted by since David Bowie’s untimely and unexpected passing—a strange thought to comprehend, but an unfortunate truth all the same. Bowie’s work touched the lives of many; his career was so dense and varied, it was as if he had been everywhere at once. And because of his extensive influence, he was solidified as an icon long before his output ever started to slow down. While his last album Blackstar is unique (and great), it made for a stunning exit, but it didn’t necessarily elevate him beyond his already untouchable status. He was already on another plane.

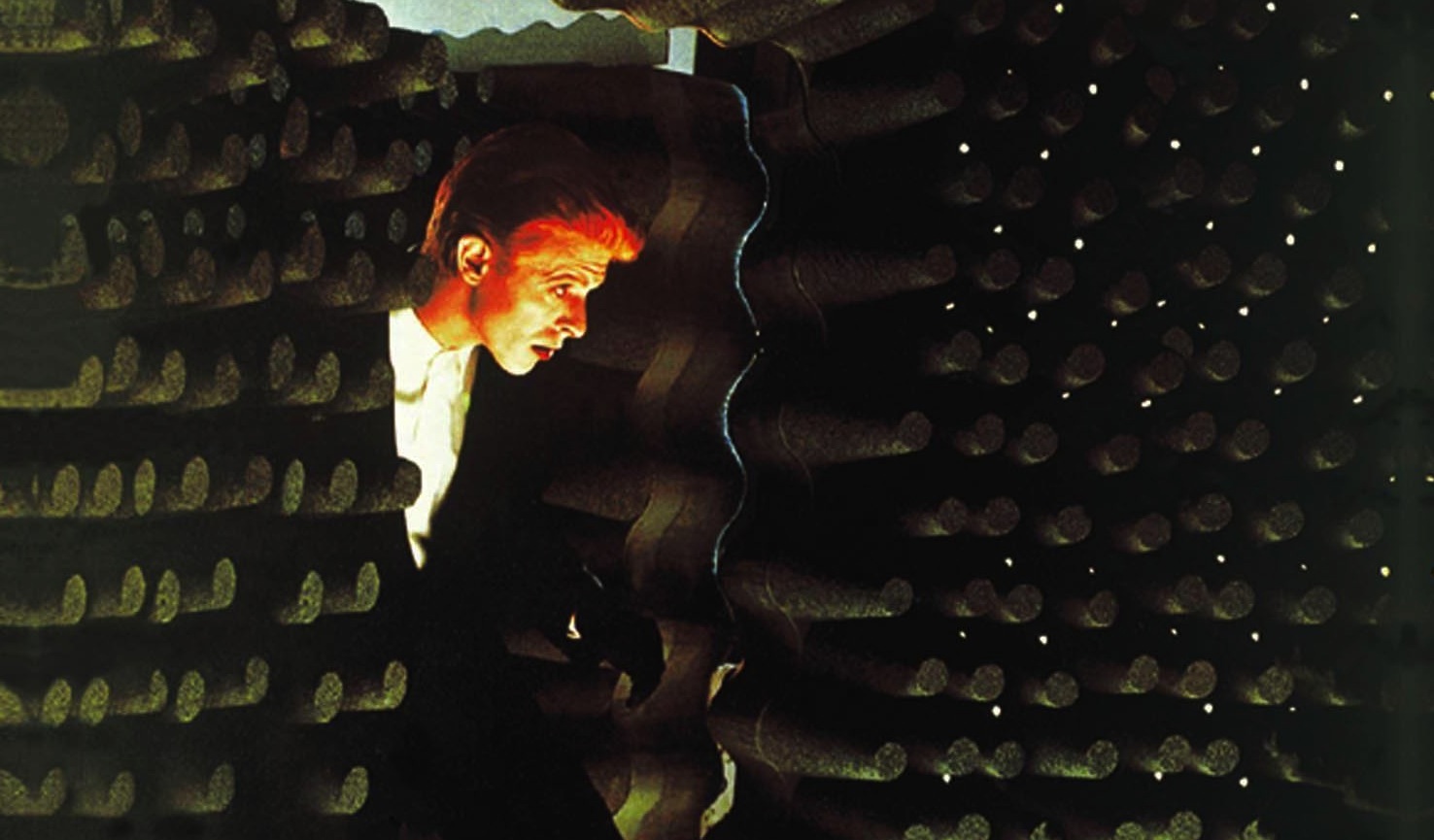

Bowie had never been interested in creating simple, mainstream music. After the glam rock days of the early ’70s, his career became much more varied and dense. At a time when it wasn’t cool to be weird, he fully embraced his creative and artistic side. He adopted different personas: The outlandish Ziggy Stardust and the iconic Aladdin Sane, both from another reality. But one character that was grounded in realism is The Thin White Duke. This role was much tamer: He looked human, had impeccable style and carried an air of mystery. These mannerisms made him more dangerous. Part of that rings true, especially during an interview when Bowie embraced fascism while in character. The Thin White Duke truly was from the farthest planet with a different perspective. It’s no coincidence the cover of Station To Station features an image from Bowie’s acting debut in The Man Who Fell To Earth. In fact, there are some similarities between The Duke and his alien character, Thomas Jerome Newton. In the film, Newton is sent to Earth to bring water back to his drought-filled planet and learns about human beings. In this case however, The Duke’s objective is to create the most engaging music while struggling with bouts of paranoia, heavy drug use and an existential crisis.

Although Young Americans was a minor precursor to the Bowie’s most creative period, Station to Station serves as Bowie’s transitional album: An exhausting overture of an extremely creative time for Bowie and the search to find his own identity within music. Glam rock for Bowie had reached its end by the mid-’70s; the next logical step would be to take the world to new frontiers. And though this made for a high creative peak, Bowie was at his worst, personally. Loaded with cocaine, Station To Station later became an infamous for being the album Bowie forgot he made. He certainly knows of its existence, but can hardly recollect how, where or when he made it.

From its opening title track, Station To Station hints it is not a typical Bowie record, the structure of the opener is unconventional at best, a 10 minute jam that begins with a minute of train noises (Later noted as a tribute to Kraftwerk’s Autobahn), an indication The Duke has arrived, ready to introduce new sonic landscapes. Soon the song begins with sustained guitar riffs, an effective bass line, tiny arpeggios, some organ and drums. The melody and structure are repeated as Bowie begins the first half with, “The return of The Thin White Duke/Throwing darts in lovers eyes.” These lyrics (along with the music) are repeated until the arrangement changes after six minutes. E Street Band pianist, Roy Bittan sneaks in his effortless playing while the rest of the band changes styles, resulting in a densely complex song.

“Golden Years,” the album’s first single, was a continuation of similar styles in his previous hit single, “Fame.” Compared to the other tracks on Station To Station, “Golden Years” was the shortest song to make. It is a fascinating track for a few reasons, most notably because it was written for Elvis Presley (supposedly), though he declined it. Furthermore, this was an example of Bowie on the edge—he was drunk during his performance on Soul Train while promoting the song. The tight rhythm section of lead guitarist Earl Slick, rhythm guitarist Carlos Alomar, drummer Dennis Davis (Both Roy Ayers Ubiquity alums) and bassist George Murray are a core part of this song’s (and really the whole album’s) success. Its structure is littered with groove and quickly became a staple in Bowie’s catalog.

“Stay” further cements these concepts and continues the trend, only to elevate it to higher standards. Conceived during their “cocaine frenzies” as noted by Alomar, “Stay” was composed by Bowie during the early sessions with only a few guitar chords and the vocal melody. Later, it was presented to the trio of Alomar, Davis and Murray where after a few jam sessions; they presented it to Bowie in its final form. Echoing similar forms, “Stay” is layered and deep, and it begins the same way it ends: Catchy guitar melodies, only to be followed by the drums, bass, congas and a droning keyboard line. “Stay” is more instrumentally driven; Bowie’s appearance is brief and his singing sounds more recited, but his time isn’t wasted. The real success of “Stay” lies within the awesome guitar war between Slick and Alomar, and Murray’s excellent bass playing as Davis and Bittan add to the atmosphere.

In keeping with Bowie’s love of space and dark humor, “TVC15” takes its influence from Iggy Pop, who hallucinated on drugs and believed the TV was devouring his girlfriend. Though here, the character decides to crawl in to find his love only to have trouble escaping. Different from the rest of the tracks on Station To Station, there’s a clear narrative and “TVC15” sounds more like a classic rock song, though its content deals with futuristic and highly relevant themes. Easily, this is one of the record’s stand out moments: Bittan’s frenetic piano playing leads the entire song while the rest follow to keep the pace, only to end with some more great guitar and bass emblematic of the singular sound of the album.

Station To Station is also an exercise in Bowie’s baritone voice, particularly with the ballads within the album. “Word On A Wing” is the closest Bowie got to writing about religion, at least during this period. In an interview with NME, Bowie mentioned he had written this song while filming The Man Who Fell To Earth, as a statement to his faith and success. The song is an acknowledgement of existence and questions about his life despite the excessive drug use and the resulting paranoia. Through his lyrics,he reaches out to a higher being to find something to believe in and a place to fit in. The composition and structure of the song is beautifully laid out. As with “TVC15,” Bittan is much of the leading musical force in addition to the eerie organ playing constantly. In his own way, Bowie created “Word On A Wing” to be his own form of redemption and his attempt to get onto a path of sobriety.

Similarly, “Wild Is The Wind” reveals more showmanship in his voice, though this one is a cover. After meeting Nina Simone in 1975, Bowie was inspired to record a version himself after hearing her style of the song. It was reported during the recording sessions, Frank Sinatra (who was in the same studio) got to hear the track and gave it praise, though Bowie was already proud of it. Bowie later remarked this was his finest vocal performance and it’s easy to agree with that assessment. Bowie’s version is distinctive from the original and stands on its own.

Station To Station changed the course of Bowie’s career. He was no longer interested in creating simple rock music. From this point forward, his work would be more diverse, intense and experimental, marking the beginning of a unique period of artistic brilliance. And for that matter, the band that performed on the record, consisting of Alomar, Davis and Murray, would remain together all the way until 1980’s Scary Monsters (with Bittan returning as well). Station To Station should be praised for the path it led Bowie down, and how it helped cement his status as musician by introducing a broader array of sounds to his music. Station To Station is a forward-thinking album that was maybe too next level for its time, and in the 40 years since its release, it remains as complicated and timeless as ever.

Writer’s Note: Part of this article’s reference material came from the blog, Pushing Ahead Of The Dame.

You might also like: