Iggy Pop : Post Pop Depression

As we approach the second quarter of The Year The Music Actually Died when more of our music heroes are floating past us in procession, about the last thing we need (or think we need) is another album posing as an epitaph. But that’s what Iggy Pop’s been hinting with his seventeenth solo album, a muscular collaboration with Queens of the Stone Age’s Joshua Homme and his most believable record since American Caesar. “I feel like I’m closing up after this,” Pop recently told a reporter for Beats. “That’s what I feel. It’s my gut instinct.”

At least Post Pop Depression doesn’t feel like a farewell. It’s not laced with the finality of Bowie’s Blackstar or even Lou Reed & Metallica’s Lulu. But it does refract portions of the Iggy Pop legend through the perception of someone who’s older, wiser, more confident and still pretty pissed off. With that directive in mind, Pop’s pairing up with Homme, a Stooges super-fan, makes a lot of sense: QOTSA’s music veers assuredly between the release of uncut rock and the restrained (I was gonna say “sober”) admission of its fallout. Unbridled Iggy would push unflurried Josh and vice versa.

That’s pretty much how it works, and the singular thrill of Post Pop Depression is how clearly Iggy puts himself across. “In the Lobby” tells it best. “I followed my shadow and it led me here,” he sings. “And it’s all about the kicks/And it’s all about the dancing pricks/And it’s all about the clowns/And it’s all about the guns.” “I hope I’m not losing my life tonight,” he wishes. Which raises an alarming question: When was Iggy Pop ever afraid of confrontation?

He wasn’t of course, and still isn’t. But the strain of violence Iggy employed in his stage act and occasionally musically was self-contained and cathartic, more of a logical reaction to the peace-and-love bullshit he had to rise above in the late ‘60s than a force to crush the opposition. Now it’s different. He sees what’s happening as a deadset mission to annhilate; people are now actually searching and destroying. The intent is nowhere near what his was, and he’s despondent that it comes from the same apparent impulse.

The rest of Post Pop Depression could be seen as an outgrowth of that awakening. “Gardenia,” a slowed-down burlesque riff on Bowie’s Let’s Dance era, finds him both aroused and disheartened by the addicted target of his lust with an “hourglass ass” (who sounds a lot like the object of desire from Lust For Life’s “Turn Blue”). It’s a true mix of Brechtian comedy and tragedy as they wind up in a “cheapo motel” where he gives her the funniest attempt at motivation I’ve heard in years: “America’s greatest poet was ogling you all night!” It’s both a great and pathetic employment of braggadocio, and that’s how it’s intended.

Iggy makes some acceptable moves towards populist understanding, working for the weekend on “Sunday,” railing against dumb corporate interests in “Vulture” and offering another hilarious but heartfelt encouragement in “Chocolate Drops.” (“When you get to the bottom you’re near the top/The shit turns into chocolate drops”—when you care enough to send the very best!) But there are two deep dives into eternity that turn the head. “American Valhalla” studies the irresolution of American exceptionalism, in which dying a hero’s death no longer has the same memorial glory of other myths. “Innocence: it’s so hard to figure out,” he says. “I’m not the man with everything/I’ve nothing but my name.” He’s rattling on the comparative youth of the U.S. and the current confusion of its standards of nobility: Is it stronger to fight or flee? The internal argument makes the payoff go further away. “German Days” is the most foreboding piece on the album, taking place in a speakeasy where the 1 percent hide out to enjoy their spoils, planning to “germinate in a German way.” The pun is convenient but the point is made: We’re exempt from our own fortunes being laid out by patricians who would rather not see us.

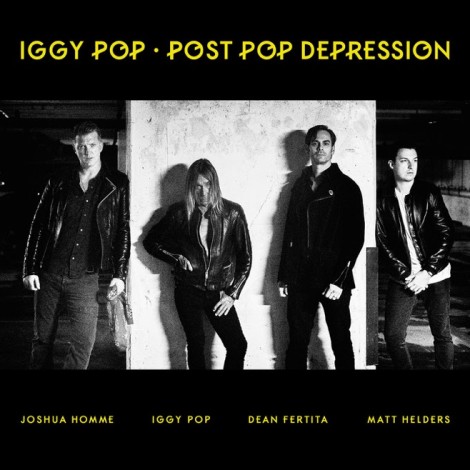

Iggy is mostly recessed on Post Pop Depression, fitting his wish in working with Homme that he didn’t want to scream too much. Homme builds a fluid, conservative backup band with fellow Queen Dean Fertita and Arctic Monkeys drummer Matt Helders. Their seeking out unexpected details to support Iggy’s plans results in the muffled vibraphones on “American Valhalla,” the robust piano in “Chocolate Drops” and the million things that happen on “Sunday” including an orchestral coda.

There’s just enough under pressure in Post Pop Depression to warrant a reckless discharge at the end, which is exactly the purpose of the closing “Paraguay.” Fed-up Iggy finally gives up on metric-loaded society and retreats to South America, where “there’s not so much fucking knowledge.” His spoken dressing down of you and me is our reward for sticking it out until the end, so I shouldn’t spoil it, except to mention the Paraguayan promise of living “in a compound under the trees/With servants and bodyguards who LOVE me!” If “Paraguay” is really Iggy’s final parting words of record, and I hope it’s not, then he’s won the title for rock’s most honest kiss-off to the Earth. Just let ‘im go, boys.

Similar Albums:

Iggy and the Stooges – Raw Power

Iggy and the Stooges – Raw Power

David Bowie – The Next Day

David Bowie – The Next Day

Queens of the Stone Age – Like Clockwork

Queens of the Stone Age – Like Clockwork

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.