Retro-Futurism: Are cassettes still a thing?

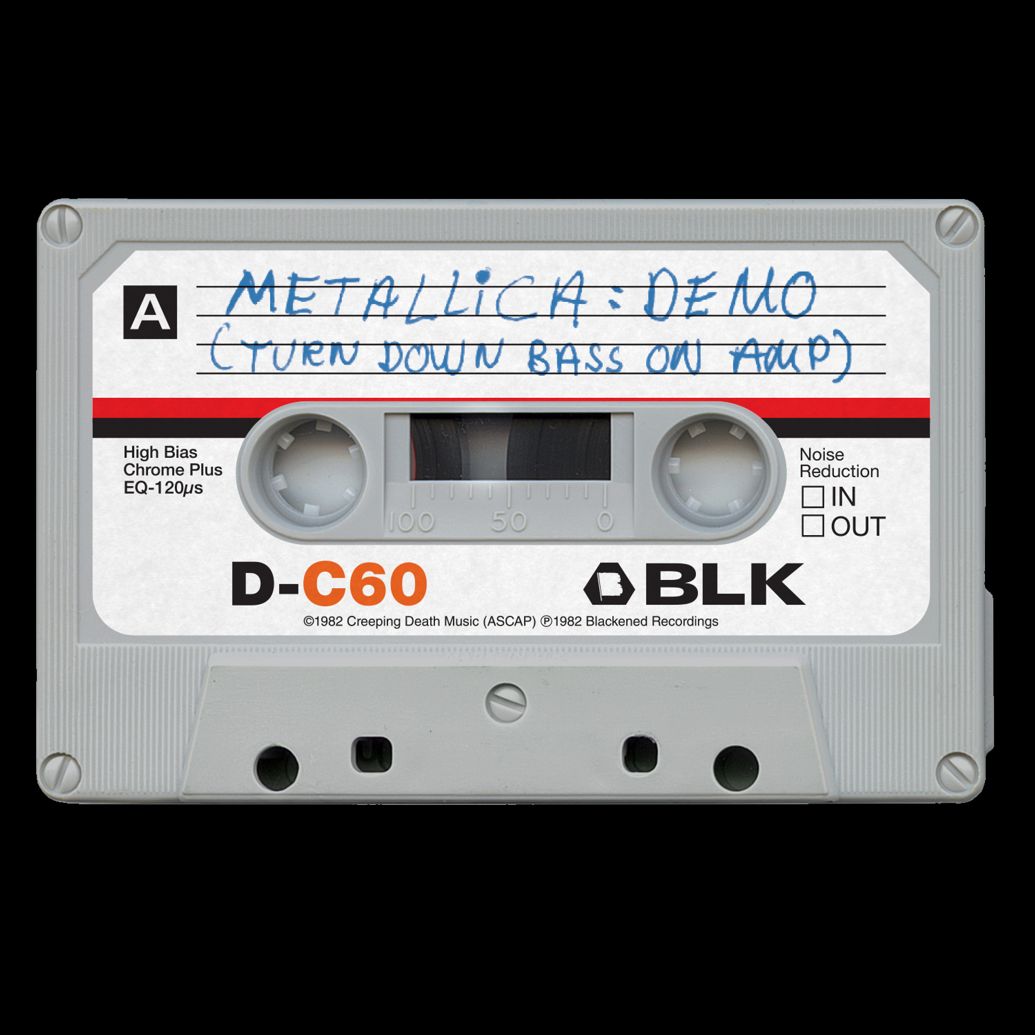

The best seller of Record Store Day in 2015 was a cassette. Metallica’s No Life Til Leather sold almost 3,000 copies. Not bad for one day of sales, from a limited edition release at that, especially since the only albums to go platinum in 2014 were Taylor Swift’s 1989 and the soundtrack to Frozen. Still, it’s a little surprising, given cassettes’ adverse past. Not only did the advent of CDs bring about the medium’s death, but the arrival of the MP3 had seemingly ensured its burial. Since the inception of peer-to-peer file sharing programs like Napster in 1999, profit from physical album sales had declined by more than $8 billion by 2009. Five years later, in 2014, digital album sales continued their decline, dropping by 9 percent while overall album sales declined by 11 percent. But the numbers have begun to reverse themselves in the last five years for a few unlikely contenders—records and cassettes.

Tapes are only a smaller part of a radical resurgence of analog media. Since 1999, vinyl sales have climbed from 2.5 million to just over 9 million copies a year. Cassette Store Day, which launched in 2013, is relatively minor when compared against its larger cousin, Record Store Day. It’s difficult to quantify the scope of the cassette resurgence. Historically, the RIAA has released shipment data for all registered album vendors, but cassette sales have been left out of those figures since 2009, presumably due to a lack of commercial interest. This effect is compounded when releases via this medium are from micro labels or the artists themselves. Bandcamp, a music platform that began in 2007, has allowed self-recorded artists to sell copies of their material while cutting out the middlemen. When most of the cassettes being sold in the United States are likely being purchased through Paypal, or at foldable tables in local clubs, it’s hard to keep track of how many are being sold. But why sell cassettes at all?

While vinyl has demonstrated its merit as a viable means of creative proliferation, the cassette is still in the process of proving itself. Audiophiles have frequently advocated vinyl for its “warmth” and lack of digital compression. As CDs and digital music took over, the realization that volume limits were virtually non-existent spurred what is frequently referred to as the “loudness wars.” Introducing a louder album on the radio would help a track stand out to the listener and hypothetically move additional physical copies off store shelves. The process of making albums louder also introduced larger problems regarding fidelity, including digital clipping, distortion and flat dynamics. A premier example of this effect is Californication by the Red Hot Chili Peppers; the quieter moments are so compressed that they sound just as loud as the distorted, electric guitars in the choruses. Mastering Engineer Adam Gonsalves told The Oregonian in 2014: “Vinyl’s volume is dependent on the length of its sides and depth of its grooves, which means an album mastered specifically for the format may have more room to breathe than its strained digital counterpart.” Ironically, the constraints of the record are what make the medium a natural promoter of dynamic range and subtlety, lauded by studio engineers and audio enthusiasts alike.

Cassettes have had no such proponents in the audio world. Most of the memories many have associated with tapes are largely inconveniences: the abrasive hiss as a magnetic strip cycles across two spools, the inability to skip to a favorite song without immaculate timing, and the brief annoyance of having the flip the tape over mid-album. The return to such an antiquated form of media seems unlikely in the age of streaming, in which the entire catalog of an artist is only a few clicks away (and in a higher fidelity).

The reigniting of a nostalgic penchant for the past among the older generation might be a decent enough justification for the increase in sales, but the simplest explanation isn’t always the correct one. Last year, ICM Research found that 23 percent of cassette buyers in the UK were in between the ages of 18 and 34, a group that towered over every other age category. For a generation that was brought up to “rip” or discard compact discs (or use them as adequate coasters for coffee tables), the re-adoption of a medium only playable in late ’80s Honda hatchbacks might appear contradictory to those who have yet to make the plunge.

Still, the retro angle and “cool” factor might be partially responsible for the tape deck’s rising obscurity. Independent music listeners have been derided for seeking out the esoteric and unheard, which is perceived as inauthentic. But this phenomenon can be found in across any group of enthusiasts, from sports to film criticism, and tends to be the product of a smaller minority of the most vocal elitists. And if today’s cassette culture was an extension of a need to be willfully abstruse, wouldn’t other entertainment mediums, such as the eight-track player or VHS, also be targeted? Taken to the extreme, it’s absurd. But this doesn’t seem to be the case.

Though cassette players have been less common of late, they are relatively easy to come by in the right places. Amazon has an assortment for less than $20 (sans shipping), and Urban Outfitters recently got in on the market. And just as the world of indie music has largely adopted the aesthetic principles of ’80s synth-pop and ’90s slacker rock, the adoption of the cassette might be looked at as an attempt to reclaim an experience that was entirely lost on a generation of young hipsters. A steady increase in vinyl units sold across the U.S. could be seen as predictive of the budding growth of tape sales. But cassettes carry with them a unique set of cultural traditions that are absent from vinyl.

The laborious process of creating a mixtape for a romantic partner or a road trip—a trial of timing and catching songs on the radio at the right moment—is an experience still referred to and glorified by films and books of the past. The Perks of Being a Wallflower, a novel written by Stephen Chbosky with more than 1.5 million copies in print, romanticizes the creation of a mixtape titled “One Winter” for a friend (championing songs from The Smiths and seminal shoegazers Ride). The book was released in 1999 through MTV Books, before an age dominated by social media. The film, which was released in 2012, revealed a continued interest in the story. It grossed a modest $33 million dollars, a figure over twice its actual budget. It’s difficult to quantify the effect that the book and film, among other works of fiction, has had on the young indie demographic, but a residual trail lies in plain sight on the internet. A playlist on Spotify with music from the novel has over 50,000 followers, and a simple search of the word “mixtape” on the music platform turns up an infinite scroll of playlists too long to count.

Of course, the idea of making a mixtape might’ve just been idyllic enough to never have died off. Mix CDs are still exchanged between fans, but the term “Mix CD” never quite took hold. That “mixtape” as a term has continued to circulate past the near-death of the medium speaks to how personal and endearing the actual concept behind its creation remains.

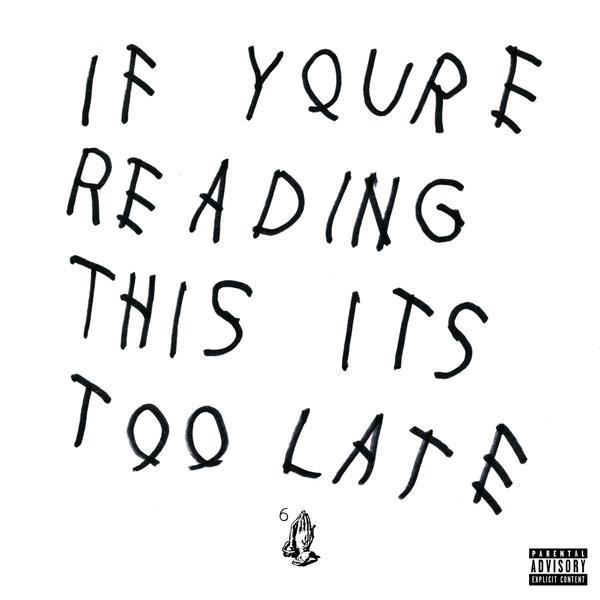

The cassette ideal extends outside of the indie realm. The hip-hop community often refers to free music releases as “mixtapes,” even when they are burned onto store bought CD-Rs or released digitally. The recent coverage of Drake’s latest release, If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late, a self-proclaimed mixtape that was put up on iTunes for purchase, had websites like Vulture scratching their heads about what actually constitutes a proper mixtape. Nevertheless, it is a notable admission that the notion of the cassette as more personal, DIY means of distribution has infiltrated popular culture without a head turn.

In California, the ripple effects of the latest cassette resurgence are most evident. There are more Cassette Store Day vendors here than in any other North American location, including New York City and San Francisco. The foremost proponent is Burger Records, an independent label and record shop in Fullerton that has released a gamut of music ranging from hardcore punk to 1960s-inspired psych pop. The inexpensive nature of the medium has allowed the label to put out smaller, more diverse limited runs. As of 2015, the number of bands on the label has blossomed into a stellar 800, many being located scattershot across almost every continent. For touring bands who are at the brink of poverty on the label, the 50-cent-per-copy cost of cassette reproduction remains much more appealing than the 80-cent-per-copy expense of compact discs.

Although the RIAA doesn’t keep track of cassettes sales, Burger founders Sean Bohrman and Lee Rickard claim to have sold over 200,000 tapes between 2007 and 2013. While those numbers are modest compared to the 450 million full-length cassettes sold 1989, they indicate a niche interest that remains profitable. Burger sells each tape for $6, a 1200 percent markup from the cost of production. Considering many of them are recorded in bedrooms and local studios, the recording costs are easily recouped. Singles and EPs, meanwhile, are sold at $8 apiece on 7-inch vinyl, rather than cassette.

Labels on the opposite coast have adopted this model as well. Mike Sniper, founder of Brooklyn label Captured Tracks, has helped reissue lost post-punk and shoegaze classics on vinyl and cassette. Each reissue will likely be heard now the way it was heard in the late 1980s—hiss, static and all. He states in an article by Noisey that “CDs are disposable, devalued objects that many consider the middlemen between buying music (when that actually happens) and uploading it to your computer.” When almost any album is widely available through torrent trackers already, the process of uploading appears increasingly arduous. But because many tapes are being offered with free digital downloads, convenience and nostalgic pastiche are able to coexist in an ambivalent harmony.

If digital downloads are included, the question becomes whether anyone actually listens to the cassette after purchasing it. Joseph Yost, the bassist for a Temecula band called The Glass Daggers, doesn’t think so. For a musician with a fondness for ’90s alternative bands such as The Pixies and Neutral Milk Hotel, it is not surprising that a pining for an ’80s medium seems irrelevant to him. The 22-year-old tells me as we traverse the sidewalks at night: “For me, it’s very strange because cassettes are probably the most inferior way you can listen to music.” Yost is hardly an audiophile, but it’s safe to say the fidelity difference is perceptible, even among those who don’t listen to much music.

In a chat over dinner, he suggests the resurgence is purely the result of visual aesthetic and social capital—a way to start off a conversation with someone, or even boast about their own taste in music: “It’s sitting there [on a shelf] almost for people to see it. Maybe everyone is buying tapes for the appearance.”

Not everyone agrees. Zach Navis is the cofounder of Riverside, California-based Not Punk Records, a smaller label with about 1,500 likes on Facebook and growing. The jaunty 21-year-old is not exactly entrepreneurial in his appearance—a band t-shirt over a pair of tight worn jeans doesn’t exactly scream label owner. Still, Navis is deeply entrenched in the DIY scene, traveling to venues across the country with touring bands regularly. He says, “I have a few opinions on this actually. I think it’s cool for the same way vinyl is cool, like it forces you to listen to the whole album instead of skipping songs, and most older cars still have tape decks.”

The novelty and lower costs of cassettes in comparison to other mediums also provides a fashionable (and cheap) way of supporting independent and local unsigned bands. Navis asserts, “Sometimes, people just like a band so much, they want to give them money. But they don’t have a record player or really care about band shirts, and tapes are usually the cheapest thing. It’s a less awkward way to give a band money without being like ‘Here is five dollars, just because I like you guys.”

///

It brings to mind a personal experience of my own. At a venue called the Blood Orange Info-shop, I had purchased my first cassette from a band called Crisis Arm—a noise-pop trio that I often played shows with during my brief period as an indie rock frontman. I recalled wanting to support the band, but not really having enough cash on hand for a t-shirt. After buying one of their albums, my girlfriend and I managed to find an old tape player hidden away in her closet. She had it because her older cousins would send recordings of stories they had made up when she was a child. I listened to the cassette through the player once, remarked about how “shitty” it sounded, and then left the tape on my TV stand. It sat there for over a year, and in fact, still does; somewhere between my broken record player and a nest of laundry quarters. I still occasionally play their music, but on Soundcloud and Bandcamp. Maybe cassettes just aren’t for me, but I don’t regret purchasing one. For me, at least, it was about supporting a band I felt deserved recognition.

After all, the novelty and lower cost of cassettes in comparison to other mediums provides a fashionable (and cheap) way of supporting independent bands. On a night in October, I decided to see how ubiquitous the medium really was at one stop on The Dodos’ tour behind Individ. The Casbah, one of the most infamous locales of downtown San Diego, has housed some of the most influential and important bands of the last two decades since its genesis in 1989, including Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins and The White Stripes. Though it’s small, it is far beyond the attendance level of the less popular DIY venues I have seen offer tapes across California and New York. If cassettes were being sold here, surely it would be indicative of a larger following than I had previously considered.

After peering across the street into the airport parking garage where my car lay imprisoned, I found myself in front of a merch table. Sure enough, I spotted a labeled cassette lying across the front of the table, placed neatly among a single CD and several LPs. I asked the woman overlooking the merchandise about whether the cassettes actually sold at all that night. She tells me: “These actually sell a lot. I’m like, really surprised. I don’t really get it, but you’d be surprised by how many people buy these.”

Though their return is still surprising, it still remains to be seen if cassettes have staying power. Navis thinks they’ll continue: “I think it will become more and more of a thing, forever. It’ll never replace vinyl, but just be more prominent. More and more, you are seeing tape and record bundles. I think it’s a collectors thing. For smaller bands right now, it’s like, ‘Okay, let’s put out this album digitally, make a tape ourselves, tour around it and sell those tapes, and then press a record once we can afford it.’ That’s almost like the new way of DIY, I think. Digital-tape-vinyl.”

Cassettes will never be widely lauded as vinyl, but they can be regarded more affectionately than CDs at least. “Vinyl will never ever stop being a thing. People will always collect vinyl, a lesser amount of people will collect tapes. People want CDs to be given away for free, at least in my experience,” Navis says. As I stare at the tape on my TV stand, I can’t help but wonder, “If that was a CD, where would it be?” And the truth is, it wouldn’t be anywhere really. It would probably be hiding in my cluttered closet, or the garage I might own in the future, waiting to be discovered by my disenchanted children.

You might also like:

It’s a myth that cassettes have inferior sound. A well recorded tape on a good stereo sounds excellent.