10 Essential Dystopian Albums

It’s hard not to think about dystopia these days. The world is becoming a less stable, less peaceful place by the hour and it’s hard to know just where all this tension is leading. We’re uneasy about it, but we also have some historical tomes as a guide—some of them in the form of music. We’ve done sci-fi albums. We’ve done political albums. But it finally seemed time that we combine the two and put together a list of 10 Essential Dystopian Albums. Truth be told, we could have just picked 10 ’80s-era metal albums and the list would have written itself, but obviously we don’t roll like that. So we begin with a ’70s glam rock concept album and travel our way on up to a fairly recent and highly elaborate album inspired by a Fritz Lang silent masterpiece. There’s a lot of different visions of a horrible tomorrow here, but the sounds that accompany them are some of the best on record.

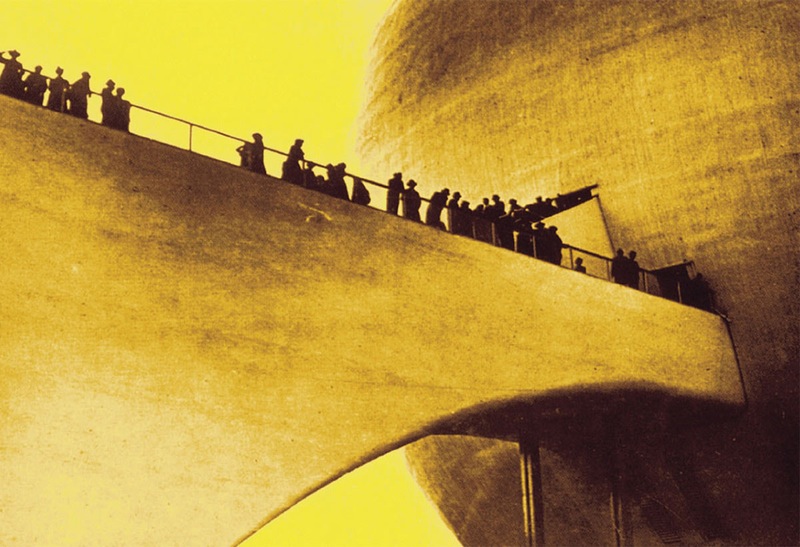

David Bowie – Diamond Dogs

David Bowie – Diamond Dogs

(1974; RCA)

David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs comprises a storyline that hews pretty close to George Orwell’s 1984. That’s not coincidental; Bowie actually wanted to create a theatrical adaptation of Orwell’s dystopian novel, but wasn’t able to obtain the rights to the work. Instead, Bowie took the songs he had written for that production sketch and turned them into Diamond Dogs, one of many concept albums he’d release in his lifetime and by far the most cohesive in narrative. Retiring his Ziggy Stardust character (and Aladdin Sane character) for Halloween Jack, Bowie retells Orwell’s story of authoritarianism, surveillance and populace control via an eclectic blend of anthemic glam rock (“Rebel Rebel”), interconnected art-rock suites (“Sweet Thing”/”Candidate”/”Sweet Thing (Reprise)”), hook-laden soul (“Big Brother”) and Shaft-style funk (“1984”). It’s one of the rare Bowie albums in which the individual songs are harder to separate from the greater whole, but that’s only by a matter of degree. There are still plenty of hits here—hits that’ll have you dancing your way toward a grim future. – Jeff Terich

Rush – 2112

Rush – 2112

(1976; Mercury)

In 1938, Ayn Rand published a novella about a society where individuality is abolished, and a dissenter is banished for rediscovering electricity through a discarded box of wires with which creates light. In 1976, Neal Peart reimagined the story as a man discovering a guitar instead of a box of copper thread, and figuring out how to make music instead of luminescence. Like the hero in Anthem, the protagonist brings this new miracle to the priests, who shun him, explaining that he’s wasting his time with this “ancient toy that helped destroy the elder race of man.” Realizing that he has nowhere to go and nothing to live for, he commits suicide (“I don’t think I can carry on this cold and empty life”).

This rock operetta comprises the first side of 2112, and even though it’s technically one 20-minute track, it reveals a side of Rush that hadn’t been seen before—a side where radio airplay is in sight. The song has driving beats, familiar structures, and cool dynamics. The other half of the album is made up of songs that are tailored for the mainstream: five three-to-four minute tracks with identifiable hooks. But it’s the first half that shows the full scope of the band’s imagination and demonstrated Peart’s objectivist leanings. – Chad Gorn

Frank Zappa – Joe’s Garage

Frank Zappa – Joe’s Garage

(1979; Zappa)

Joe’s Garage is one of the most ambitious recordings in all of rock. Zappa took the concept album to the Nth degree with this three-record set, totaling nearly two hours of music. The narrator, the whispering “Central Scrutinizer” sets the exposition quickly in the first line: “…it is my responsibility to enforce all the laws that haven’t been passed yet.” He tells the story of Joe, an adolescent (played by Ike Willis) who just wants to jam in his garage. However, in this society, music is a “horrible force,” and a neighbor reports Joe to the police. He is released, encouraged to participate in “church-oriented social activities.” However, his girlfriend gets seduced by the glory of being a groupie, leading Joe down a dark path. He falls in with the wrong crowd, sleeps with a girl who works at the Jack in the Box, and gets the clap. Joe falls in with a cult, L. Ron Hoover’s First Church of Appliantology, whose members frequent a bar called The Closet where folks like Joe can “plook” electronic devices, such as “a cross between an industrial vacuum cleaner and a chrome piggy bank with marital aids stuck all over its body.” Well, as you would expect, Joe’s golden shower shorts the machine, and gets sent to prison. All because of music. Interspersed in the story are musical interludes that represent some of Zappa’s signature minimalist compositions, but Joe’s Garage also provides a platform for him to deliver a message of anti-censorship, a stance he became the public face for in many respects. – Chad Gorn

Big Black – Atomizer

Big Black – Atomizer

(1986; Touch and Go)

Steve Albini’s vision of dystopia was, apparently, the 1980s in America. In fact, there’s probably been no bigger catalyst for angry punk rock than the Reagan era, though we’re about to see how much that changes. Nonetheless, Big Black’s focus on humanity’s depraved nature led to a portrait of American society that looks, frankly, fucking grim. Incest, addiction, setting shit on fire—it all gets a fair shake on Atomizer, which is almost as intense and twisted musically as it is lyrically, thanks in large part to Albini’s preference for treble-heavy guitar slice and the band’s menacing electronic beatmaker: Roland. But considering Albini had a tendency to set off firecrackers before the band’s shows, he wasn’t necessarily judgmental about anyone who wanted to set shit on fire. With songs like “Kerosene,” he just made it seem that much more grotesque. – Jeff Terich

Voivod – Dimension Hatröss

Voivod – Dimension Hatröss

(1988; Noise)

Canadian prog-thrash pioneers Voivod’s fourth album, Dimension Hatröss, is the last chapter in what could be considered a tetralogy of dystopia. Their first three albums are themed around nuclear war, sweeping annihilation and technological destruction, but Hatröss is a fully-realized concept album. Abandoning the world obliterated at the end of Killing Technology, monstrous mascot Korgüll creates his own universe (“Experiment”). Planetary construction and evolution are swift as inhabitants progress from primitive beings who see Korgüll (rightly) as their god (“Tribal Convictions”) to a society divided into the rebellious controlled (“Chaosmöngers”) and the malevolent controllers (“Technocratic Manipulators”). That’s the “Prologue” (or “side one” on vinyl). Side two is the “Epilogue,” making it clear that in this dimension, there is only a beginning and an ending. The Chaosmöngers resist the mind control that they are subject to, and Korgüll finds himself caught up in it, having his brain scanned like the rest. He is able to overpower the Manipulators, and, without regret, destroy the entire creation. Musically, Hatröss was a turning point for Voivod. They experimented with soundscapes, textures, progressions, beats and melodies that shaped their following releases and inspired a genre, but the deep and timeless parable of the birth and death of civilization drives the album. – Chad Gorn

Deltron 3030 – Deltron 3030

Deltron 3030 – Deltron 3030

(2000; 75 Ark)

Conceptual, futuristic hip-hop was already a thing by the time Del tha Funkee Homosapien, Dan the Automator and Kid Koala teamed up for their Deltron 3030 project in 2000 (see: Dr. Octagon). Yet this vision of a nightmarish technocratic future was a bit more elaborate than any dark, forward looking rap records before it. It’s also a lot of fun, in spite of the landscape it rolls out, littered with corporate overlords, computer viruses and mind control. And how couldn’t it be: Two expert beatmakers teaming up with a legendary emcee could only produce something that ends up sounding like a party record, even if that party is on top of the ashes of our long-dead civilization. – Jeff Terich

Radiohead – Kid A

Radiohead – Kid A

(2000; Capitol)

It’s fairly easy to make the argument that every Radiohead album touches upon the dystopian to some level, be it the technological absurdities of OK Computer or the more explicit political statements of Hail to the Thief. Kid A is the one that sounds most like the future, which actually makes its themes of a bleak tomorrow feel that much easier to visualize. At times, Thom Yorke’s lyrics are cryptic at best, as with his distorted repetitions in the title track. In other parts, he’s simple and direct, singing “Everyone has got the fear” in the unusually funky “The National Anthem.” And at others still, like the glimpse into the inevitable endpoint of Global Warming on “Idioteque,” it’s beautiful and horrific at the same time. Leave it to Radiohead to make a living nightmare seem breathtaking. – Jeff Terich

The Thermals – The Body, The Blood, The Machine

The Thermals – The Body, The Blood, The Machine

(2006; Sub Pop)

Imagine for a moment that America has descended into authoritarianism by a religious fascist government. Far fetched, right? Ugh. On the Portland indie rock trio’s concept album about a right-wing rule taken to its apparently not that exaggerated extreme (released during the second of George W. Bush’s presidential terms), the Good Book replaces the Constitution and free thought is stamped out. Or as Hutch Harris puts it in “I Might Need You To Kill,” “They’ll drown your disease/They’ll pound you with the love of Jesus,” bringing new, literal meaning to the phrase “bible thumper.” It’s a good thing the songs are so damn catchy, otherwise this future might look a little too bleak. – Jeff Terich

Nine Inch Nails – Year Zero

Nine Inch Nails – Year Zero

(2007; Nothing/Interscope)

Of all the dystopian tales to pervade the arts, from film and music to literature, Nine Inch Nails’ 2007 harsh electro-industrial concept album Year Zero may be the closest to the current situation of the United States. It focuses on a United States that has been overtaken by the religious right (check) in the guise of a nationalistic movement (check), with essentially continuous war against a non-Christian foreign “enemy” (check), and tells a variety of stories within that framework. There’s also some shit about The Presence (which is totally aliens, based on “The Warning,” the song focused on it) and hints at mind-altering drugs being introduced into the country’s water supply.

Year Zero is complicated. And it doesn’t all hang together, but is there any concept album that has? What’s important is how sociopolitical anger dragged NIN mastermind Trent Reznor away from his wheelhouse of personal angst and isolating depression, and also reinvigorated his sonic creativity. In NIN’s sizable catalog, only Broken and Not The Actual Events contain as much sustained chaos as this album. Reznor made Year Zero with multi-instrumentalist Atticus Ross and just a few session hands, and this small group made great cohesion. From the dystopian rock boogie of “The Beginning of the End” to the dark hip-hop of “Me, I’m Not” (one of NIN’s most underrated tracks) and the all-out hellscapes of synthesizer/glitch-beat noise within “Vessel,” “My Violent Heart” and “The Great Destroyer,” Year Zero brings the listener fully within the passion of Reznor’s radicalized fury and is the most coherently focused NIN album aside from magnum opus The Downward Spiral. – Liam Green

Janelle Monáe – The ArchAndroid

Janelle Monáe – The ArchAndroid

(2010; BadBoy)

Experimental and bold, The ArchAndroid is an eclectic concept album set in a rich Afrofuturist world of Janelle Monáe’s creation. In it, Monáe adopts the persona of a heroic scapegoat android, Cindy Mayweather, using the powers of time travel and love to fight an oppressive regime, drawing from various genres—from gospel and soul to funk and psychedelia—to tell the tale. The ArchAndroid seemingly does absolutely everything, but it’s all done so masterfully. Monáe tells its story so vividly that the danger and love are palpable, and the album transcends its medium to become a stylish, thrilling guide to resisting and surviving a dystopian future. – Paula Chew