Interview : Sean Nelson

Talking with Sean Nelson is like accessing a non-existent photo album featuring all the cars I drove from high school until a few years after the iTunes era began. That’s because the floor of the passenger side of every car I owned was completely covered with cassette tapes, then CDs, strewn about in a mess. But they had to be there, because I needed instant access to them if I had the urge to put something in the player. If I needed to scream down the streets of Sacramento and New Day Rising was stuck at home, what good was that going to do?

Which is not to cast aspersions on the floor of Sean’s car – just to say that it’s like chatting with someone else for whom music has been a backbone for almost every discernible moment in his life. Nelson came to national attention via Harvey Danger, whose 1997 album Where Have All The Merrymakers Gone (which, yes, spent some time in my car) yielded a certifiable modern rock radio hit, “Flagpole Sitta.” Nelson’s bio at Really Records’ website boasts the song as “an out-of-nowhere anthem that can still be heard at karaoke bars, sports arenas, and one excellent British sitcom.”

Harvey Danger was still active until 2009. The decade-plus between “Flagpole Sitta” and their demise found Nelson pursuing several alternate avenues: forming The Long Winters with John Roderick, working with Death Cab For Cutie, The Decemberists, Robyn Hitchcock and others, acting in several movies from Seattle film director Lynne Shelton (including the lead in My Effortless Brilliance), and writing a short book about Joni Mitchell’s Court And Spark for Continuum’s acclaimed 33-1/3 series.

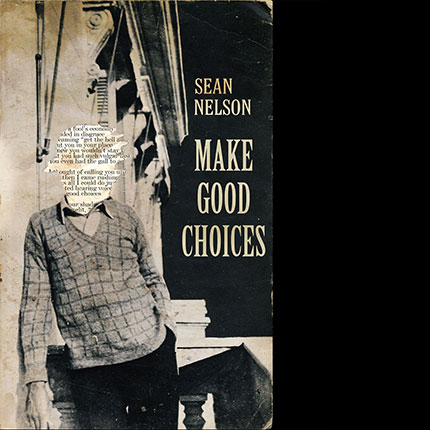

Nelson has just released his first solo album, Make Good Choices, a remarkably intimate, cutting and humorous set of thirteen songs where music is both vehicle and strong supporting character. Recorded over the course of a few years with collaborators like former REM guitarist Peter Buck, Death Cab For Cutie’s Chris Walla, members of Centro-Matic and more, Make Good Choices is both long overdue and just in time.

He’s also a former workmate of mine, from when we used to work at a respectably sized merchant of computer-based products that shall otherwise remain nameless. We met up at a coffee shop in Seattle’s Columbia City neighborhood on a temperate Saturday evening in June. The recorder ran for an hour and a half. This is the most partial of transcripts as I could conscientiously make.

Treble: This was recorded over a span of a few years?

Sean Nelson: Yeah, seven or eight. The first session was in 2003 or 2004 in Denton, Texas. There are three different chunks of the record, one of which is just one song, “Advance and Retreat.” Four I did with Chris Walla where he plays all the instruments except drums. He wrote the music, and I wrote the words and melody, and we just fused them. The others I did in Texas with the guys from Centro-Matic.

Those were sort of what I thought the album was going to be. I didn’t have a main thing, so I thought any one of these could be that. The four songs with Walla were great, but he has a band. He didn’t have time to be in another band. I really didn’t either. So at a certain point I listened to them all and thought, “These are the record.” It had been all along, I just couldn’t see it.

Treble: Even though it was recorded in piecemeal fashion, it has a unified sound. It doesn’t sound like a hodgepodge.

SN: I agree, and I’m very excited about that. There are themes running through the songs. I didn’t necessarily intend that, it’s just what I always write about. I’m basically just a singer, I only play well enough to write. I play on a lot of things on the record, but I also don’t.

I’ve always felt there’s a mystification of the recording process, a kind of preciousness about intention, the whole issue of control, whose idea it is. The record needs to be made a certain way. But by and large I feel, especially in the independent, “un”-dependent world – undie rock (laughs) – people are weirdly precious about that kind of thing. At a certain point, you don’t have to book time in a studio and do it all at once.

Treble: Plus recording has become more of a personal thing that you can do in your own isolated space.

SN: By the same token, though, I feel there’s something almost immoral about people taking credit as a producer, if they really don’t earn it – and by “earn it,” I don’t mean sit in a comfortable chair by the board. There’s the importance of knowing fundamental things about audio engineering, but do you know how to wire a circuit? If you don’t, I don’t really think you should call yourself a producer.

Of course I don’t know how to wire a circuit. I don’t even really know what a circuit is. But I have real respect for people who put in the years of hard work it takes to get good at that.

Treble: “Creative Differences” could have been the title song. Music you’ve heard before sets up this context for something that sounds more like a relationship issue than a band breaking up. Do you find yourself, not so much comparing yourself to the music you grew up with, but using it to frame your story?

SN: It’s interesting: I’m married to someone who’s a bit younger than I am, and she doesn’t share the same musical frame of reference that I do. She’s a classical musician, an outsider folk person. If I were to make a classic rock reference as I do in this song, it doesn’t necessarily hit the same register. But what you identified about the close tie between the band dynamic and the dynamic in a relationship – it is a relationship. They’re the same thing in some ways.

You need only read a couple of books before you realize every band has the same story. It has to do with the tension between being fully part of the group and surrendering yourself to that, and the need to be an individual apart from the group so that you’re bringing interesting things into it. That’s the same in a romantic relationship – you need to have a certain amount of freedom, of the opposite. The idea that the only way people have of expressing power in these dynamics is to withhold themselves. It’s really hard to find your way through it.

Treble: There’s a lot of startling lines in it – “you be the symphony and I’ll be the cover band.” You’re willing to forfeit your glory and let them have everything just to maintain some sort of peace.

SN: If you look at it on the page, it could very easily be somebody offering that graciously. But the way I sing it, it’s more like “Fuck you. This is what I signed up for?” There’s that layer of sarcasm. It’s caustic. At the same time, the ego vs. anti-ego gestures of any relationship are always there.

Treble: I have to say the line that made me laugh the loudest was from “Creative Differences”: “I was down by the river, but I couldn’t shoot my baby.” (laughter) That’s a great payoff of the structure you’d set up.

SN: That’s where, in a way, it’s where the rubber hits the road. It had to be another reference. The second half of that line, “I wouldn’t be here if you paid me” – it was different for a long time. I never liked it. I felt like the song wasn’t going to work if I couldn’t make that line pay off. Then I read that book Shakey, Neil Young’s biography. I don’t know if it was an interview or if he said it directly in the book, but he said, “’Down By The River,’ you know what that song’s about, right? It’s about blowing your thing in a chick.” Blowing your thing in a chick?

Treble: I was thinking about the music I listened to, growing up. Much of it suggested a sort of idealism. “We’ll all work together. Love will be like this.” I’m wondering, 25 years down the road, do you ever want to hold those songs accountable? (laughter)

SN: I want my money back! The ultimate example of that is on (Nirvana’s) Nevermind, where on “Territorial Pissings” they sing “C’mon, people now, smile on your brother!” (from the Youngbloods’ “Get Together”). Real disdain and mockery. I heard “Get Together” the other day. I don’t know if it was the original version or some knock-off from the same period. I was perplexed by the language. What does it mean to “smile on” something?

Utopianism is a very dangerous impulse, though it’s alluring. The ‘60s bands went pretty deep into that. Even ones who had that particle of being cautionary, like The Who. Townshend was worldly in some ways. But he never really quite let go of that messianic thing. He might claim that he’s writing “about” that in Tommy, but really he’s living it out. That’s the power of that music and why it’s still captivating. Phil Ochs wrote some pretty snide-ish songs. But always from a position of, “Can we get back to the utopia idea, guys?”

Leonard Cohen’s album, Songs Of Love and Hate — that’s a guy who is really falling apart. He’s in the sinkhole, grabbing and taking everything down with him. That kind of destructiveness, “I’m not gonna pretend this isn’t happening,” expands the possibilities of music far more than it limits. It’s not mere cynicism. There are cynical songs and I don’t usually like them much. Even though it’s good for a song to illustrate a feeling in a kind of monochrome way. We’ve all felt cynical.

But I also feel like cynicism presents a sort of foregone conclusion that everything is hopeless. I don’t really know how useful that is after awhile. It’s kind of wallowing. Not to say I’m not a wallower, personally. But there are always those moments where you’re like, “I have to stop wallowing,” where you start to figure things out.

Treble: The title track reminded me a lot of “Don’t Get Me Wrong” by the Pretenders. Was that kind of an answer song?

SN: No, but that’s a really interesting thing. I’ve never thought of that. It’s not like a Pretenders song that I go to. I mean, I’ve heard it a million times.

Treble: When I was stuck on ideas I would try to answer or update somebody’s else’s song. There’s the legend of Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville being a straight response to Exile on Main St. Is that something you ever do?

SN: I’ve been thinking about that a lot, because it comes up when I’m talking to people. There’s a lot of references to things on the record. In all of my songs that I’ve ever done it’s a thread. But it’s not a question of name checking or demonstrating that I know that reference. There are easier ways to do that. I like it when songs know that they are songs.

It doesn’t mean that’s all they are, they’re part of this really broad continuum. With almost all of my good friends who draw in the same pool of musical knowledge, it’s common for someone to say, “Check that expiration date, it’s later than you think” in conversation. It’s shorthand for “let’s not forget that songs are really important ways to see the world.” That Pavement line is not just funny, not just clever; there’s something really true in it. I’m sure Stephen Malkmus would deny it forever, but the wisdom that exists in pop lyrics is something that, from a very tender age, was clearly to me profound wisdom.

It’s not that you live by it. I’m not gonna “smile on my brother.” But any meaningful art just sort of lifts or opens the shutters a little bit. You understand the world just a bit more.

Treble: As a person who wrote about music, with this critical, literary knowledge of it, does that make it harder for you in making your own music? Do you ever say, “Well, I’ve set myself some standards that I’ve gotta live up to?”

SN: That’s a fool’s errand to try and live up to the people you revere. But I know exactly what you mean. I’m incredibly self-critical. I feel that has more to do with a psychological hang-up about laying claim to your own worth as a human being, rather than, “Oh God, is this as good as Abbey Road?” Because it’s not as good as Abbey Road.

There’s still, unaccountably, this strain in writing about music and talking about it, where people want to make the best album ever, to rise to icon status. It’d be ridiculous for me to pretend that was part of my M.O. If that were why I wanted to write songs I would have stopped a long time ago.

The little taste I had of being quite popular for a very brief moment with one song – it sucks. I can’t really complain about it, because there are good things that have come from it. But generally speaking, if you want to say anything complex, it’s the wrong racket. The mass audience, the wide readership, is the wrong venue for complicated ideas. There are a lot of people out there who appreciate that and are willing to look into it.

Treble: I think there’s always been more people like that than the industry thought. Now that the industry is kind of in a tailspin, people are discovering that.

SN: The great quote about audiences for me is from Momus, who changed the famous Andy Warhol line to “In the future everybody will be famous for 15 people.” That’s a clever aside, but it’s incredibly insightful and accurate. Because of the internet, and because the music industry poisoned its own well and is only now starting to realize, “Hey, this water tastes like poison!” There’s not one audience, there are audiences. Some of them overlap. But are you doing it to get people’s attention, or because you just have a desire to do it?

Those aren’t mutually exclusive things, but for me, when Harvey Danger had happened and then was just over, I was like, “Wait — I didn’t ask for it, but I don’t even get it anymore?” Like in Annie Hall when Woody Allen goes to do the awards show and gets food poisoning, and he goes, “Wait, I don’t even get to do the awards show now?”

I feel, having succeeded and then by some definition failed to follow up, there’s a potential embarrassment factor in trying again. You see it in reviews, in the margins of things people write. They’re not even necessarily doing anything, but a photograph will appear of somebody that was moderately famous a long time ago. The way people talk about it online – “Oh, that guy’s still alive? I can’t believe he still exists!” It’s the refractory lens of fame as the only justification for anything in the world. It’s only in the last ten years that it’s become the unadulterated coin of the realm.

Treble: They seize the moment to say something snarky because they feel pressure to say something smartass. They probably don’t feel strongly about it one way or the other. I guarantee that whatever ultimately destroys the planet will start in a comments section. (Laughs)

SN: Right. It’s like the doctor hitting your knee with the rubber mallet. You’re gonna kick. But it also works the other way. Make Good Choices was recorded, and kind of takes place, during the decade that I gradually stopped following popular music. My hunger to keep up was just gone. Still love music, still completely in awe of what I’m in awe of, but needing to know what every band sounds like? It’s gone.

Treble: “Born Without a Heart” has an interesting angle to it. A couple of times on the album there’s mourning, almost scorn, over lost intimacy, and how that changes over the span of 15 years.

SN: It’s not that your friends aren’t important. It’s that it’s wrapped up in sentimental, wishful thinking. If you say it enough times it’ll be true. But friends are often not able to be there for each other as they get older. They tend to drift. It’s not inevitable, and it’s not like you don’t have agency in that. You could work harder, I could work harder. But as weirdly as the world has become more interconnected in very shallow ways, deep connections become harder and harder to maintain.

Treble: You mention those distractions in “Stupid and 25.” “Here’s your distance, you can keep it.” “Keep your sycophants closer.”

SN: Here’s Your Distance, You Can Keep It was a running title for the record for awhile. Sometimes there’s a fight, or a blow-up, or a cycle where you both think the other one is mad at you, so you don’t call. Something in the distance that develops between friends as they get older has to do with preparing for death, frankly. “Born Without a Heart” is explicit about that. I know that life is miserable — all these things that you’re worried about are probably true. But that’s not the only way. We can actually be there for each other. I believe that, but it’s hard to maintain.

Treble: “Advance and Retreat” reminds me of when I was 17. I was trying to figure out how to get along with the rest of the world. My demonstrations or emotions, or the ways I gave things, was just too much. I didn’t really learn how to do that correctly until… age 37. (laughs) It’s scary because it says when in forming relationships we think that over-sentiment is enough.

SN: I know exactly what you mean. It’s funny, because even though it’s evocative about the way things go when you’re young, it was the last song that was written for the record. It has to do with how on both sides of that romantic equation there’s strong desire and fear. One’s fear leads them to be cautious, still saying, “I want to do this… but I don’t know if I can do it.” Meanwhile the other person’s fear is, “Oh, maybe they’re not gonna want to do it.” So you charge at it like a rhino, and it’s not what’s called for. But then you feel, “I have all this feeling. I want to make sure it is expressed in the event that that’s the problem, that I’m not expressing enough.” Really, patience is the only thing for it.

Treble: “Kicking Me Out of the Band” – obviously, that’s not about you, because it starts in Britain. Like “Creative Differences,” it sounds like a story of something you could go through.

SN: I was in England reading the NME, about this band I’d barely heard of. I knew they played America a little. This article was a two- or three-page spread about the people that have grown up with this band, how they’ve changed our lives forever. Obviously, the British press are about hyperbole. But this seemed outlandish. I still was a devout follower of rock band culture. I’d never heard any of their music, but not only that, I’d barely heard of them.

The classic story of one guy developing a drug problem and treating it like it’s a superpower – that really happens to people. I heard a story about someone I didn’t really know, but his music meant a lot to me. He became a junkie. People would say, “You gotta clean yourself up, or I don’t know if I can work with you. I really want to work with you.”

And he said, “Don’t tell me I can’t do heroin! Keith Richards did heroin! Are you saying I’m not as good as Keith Richards? Look at Lou Reed, I’m as good as Lou Reed!” Well… nooo, you’re not, actually. But he used anything to justify self-destruction. The song is really about that last line, the guy saying, “You’re afraid to even try.”

Treble: I caught a whole lot of things on “I’ll Be the One.”

SN: You know that’s a cover? It’s a Badfinger song. It’s a B-side. It’s on their Greatest Hits.

Treble: I did notice a different tone. The vocals reminded me of a few duet records – Lennon & McCartney, Alex Chilton and Chris Bell. Do you ever use certain records as blueprints?

SN: I think I am more likely to unconsciously rip something off, than I am to set out.

Treble: But it’s not a rip-off…

SN: No, I know what you mean. I’ve caught myself writing a song, feeling like it sounds like something. Of course in your mind, you’re like, “This is an amazing melody I just came up with!” And then, “Oh… It’s in twelve other great songs. I should probably do something else.” But although my melodies are in a tradition, I never hear them being too derivative.

“I’ll Be The One” I like because I was really obsessed with it for awhile. I really like Badfinger, and they’re such a hard luck story. They had it all at once. Then everything that happened to them was the saddest, worst thing ever. They were normal guys, from what I could tell. They weren’t pretentious, they weren’t artistic. Just big-time, rock band dudes.

Treble: “More Good News from the Front” felt a bit like XTC.

SN: That’s one of the four I co-wrote with Walla. He’s obsessed with English Settlement, and Drums And Wires to a lesser extent. Or at least he was around that time. I hear that, and I hear implied Talking Heads. They were a lot more authentically funky. Even though this record isn’t a good indicator of this necessarily, I just love screaming rock and roll songs.

Treble: “The Price of Doing Business” – I know this is probably not what it’s about, but I remember thinking, “Oh, I hope this song’s about the place Sean and I both worked at once.” (Laughs)

SN: It predates that job by several years. I played this record for somebody when it was in progress. And he said, “I just could never be as finger-pointing as you are on this record.” He didn’t mean it as a diss, exactly. But he was being serious, there is a lot of that. The “you” is often me, just as much as it is another person. It moves around a lot. But a lot of the songs do often live in the blame.

Treble: That’s almost what rock and roll is about to begin with, a pent-up reaction. It’s all protest music.

SN: There’s the Beatles song “You Can’t Do That.” There’s Elvis Costello, one of the Mount Rushmore faces for me. I feel like so much of being alive consists of wondering what the hell other people could be thinking. You talk to them about it, and often can’t get the whole story. If people feel accused they’ll feel defensive. Really, all you want is to get the facts established. That becomes hard. I think that’s what that song is about, it’s very much about how to hold a grudge.

Treble: “Stupid and 25” I thought was about every person we’ve ever known, including ourselves when we were stupid and 25. It’s not a strictly me-versus-you proposition.

SN: Exactly. That one’s based on an actual thing that happened. But it happened when I was 25, and that was 15 years ago. By the time I’d written the song and recorded it with Peter I wasn’t attached to those feelings at all anymore. That’s all the more reason why it’s kind of easy to understand that even by making these observations, I hope, the song is admitting that it’s a universal experience.

Treble: There’s always this implied, fallacious understanding that if you put it on record then you must really be or feel that way. It’s tricky when you’re dealing with people who have incomplete experience with how art gets made.

SN: Music is kind of the most direct example of this that I can think of: When you say “I do anything” in the song, it is understood that you’re saying you really do it. It’s fun to know that it’s not true. But it’s also tempting to then kind of advertise yourself as a heroic figure or this great victim, or a Messiah. Even great singer/songwriters either use that and then fall into the trap of it, or maybe don’t even make the distinction.

I always think the self is a really important subject. It’s where we all live, it’s what we’re thinking and talking about. For a song that has a complex treatment of that is valuable, at least to me.

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.