On ‘In the Court of the Crimson King’, King Crimson set the bar for prog rock

This has been a long time coming. This is true in multiple senses—progressive music has been on the rise culturally over the past roughly decade and a half, finally breaking through the barrier of a few artsy bands dabbling with the concepts to being as common a musical pool of influence as post-punk, jazz, hip-hop, etc. The tendrils of progressive music in 2019 are beautifully, ecstatically varied, from having an effective aesthetic marriage to underground metal no matter the dominating sub-genre to being the guiding hand behind a lot of the more brilliant excursions in rap over the past decade to an increasingly obvious presence in electronic music. This, of course, excludes the tremendous records and in fact entire discographies and fields of work in the prog genre proper, with bands such as Big Big Train, The Tea Club, The Dear Hunter, IQ and more producing brilliant works within the genre, be they older bands returning with new works or younger bands invigorating the field. So it feels proper to have a space that catalogues and explores the field as broadly as possible, whether stalwart classics from bands like King Crimson and Yes, bands as mandatory for a keen ear as Nas or Prince or The Ramones, to contemporary work to records and artists who are often excluded from discussions of progressive music, be it instances of misogynistic reclassification in the case of Kate Bush and Tori Amos to racist reclassification in the case of Kanye West, A$AP Rocky, Danny Brown and Shabazz Palaces to indie music’s generalized shame and derision keeping groups like Radiohead and Liars from being incorporated into the story of prog. We see other columns and spaces held for heavy metal, for rap, for emo, for post-punk, for jazz, all necessary and vital explorations. Now, it’s prog’s turn.

It’s also been a long time coming on a personal level. My personal love of extreme metal is well-documented; I did not take on a role as editor for Invisible Oranges nor did I gain a column titled I’m Listening To Death Metal there for nothing, and I’ve written more than my fair share of metal writing here and elsewhere as well. As much as I write about other spaces of music, I constantly readmit and find reaffirmed my love of heavy metal. Metallica, after all, was one of the first bands to ever imprint itself upon me, to feel like it was mine and not just the music I heard around me, and the primal darkness of “Fight Fire With Fire” and “For Whom The Bell Tolls” still resonates in me as some of the best and most personally important music I’ve heard in my life. But there is another great wing to me, one that finds itself often entwined with this love of heavy metal, and that’s my love of progressive music, from the cheesy and brash capital-P Prog of bands like The Flower Kings to the subtle, elliptical and richer works of Toby Driver’s various projects. This love of progressive music has been a poorly-hidden potent throughline to a great deal of my other writing and choices of coverage, with works by Steve Hauschildt and Mono and even my recent writing for the number one spot for our album of the decade To Pimp A Butterfly partly built around those works’ resonance with the style, aesthetics, methodologies and modalities of progessive music. It feels necessary to me, as necessary as writing about extreme metal, to write the lived and internal story of progressive rock; not just the outside tail of its critical successes and failures nor its occasional acceptance but also as someone who’s personal life has been touched, shaped, moved by it, much in the same spirit as our writer Brian Roesler’s powerful serial covering the history and influence of emo over time or our editor-in-chief Jeff Terich’s consistently brilliant column covering metal.

What’s frustrating is that this is not a column that, historically speaking, would always have been necessary. There was a period from roughly the mid-’60s where deeply adventurous music found not only increasing critical and artistic success but also commercial acceptance as well, newly-adopted radio formats where DJs were encouraged to play album cuts to save money and fill space incidentally exposing people to wider experiments in sound, exposures which would then inspire a new group of people and players to expand upon what they had just heard. In that space, progressive music was not strongly differentiated from psychedelic, avant-garde, or generically experimental music, nor should it have been. The important component—arguably the only important component—that of fearless adventure in arts, was the common thread, and so groups like Quicksilver Messenger Service, Procol Harum, the Moody Blues, the Electric Prunes, Beach Boys and Velvet Underground found a shared listenership with Stravinsky and the early experimentalists of electronic music and composition from the ’20s through the ’60s. Within that space, prog as we know it was a small bubble in a field of bubbles, a field which could broadly be described as “progressive.” It was only in the rise of punk that a misunderstanding seemed to arise, formulating not that punk was a necessary force to rebalance what could constitute a good record or song but, broadly speaking, somehow a more essentially correct way to go about things.

This is no fault to punk itself. It is 2020 and punk as we know it has existed for just under 50 years with roots going back even further, which often find themselves entangled with those of progressive music as well. In that time, an unreasonably countless number of great genres, aesthetics, artists, records, songs and sonic ideas have been born from it as well as a powerful and necessary energy for music that permeates not just rock and underground music but also spaces like hip-hop and mixtape culture that continuously feeds that genre new blood and musical ideas. The fault instead falls more on relatively constrained set of music critics and music fans who, in growing bored with one form (this conceit started within that narrow band) and began to favor another, accidentally created a narrative regarding that style that effectively killed all commercial and even broadly critical chances of it for decades to come. Some bands ceased to exist entirely in the late ’70s and early ’80s, some changed their shape radically, while others had members splinter off to pursue new bands or solo projects of varying contexts. There was a resurgence of sorts in the ’90s, but it was an underground movement that by sales and coverage was significantly smaller than even a known underground entity like death metal was at the time. When a band did break (relatively) big of the style—Dream Theater or Opeth or Mr. Bungle or Tool or even Radiohead—there seemed always to be guarded words, a sense that they were only good or respectable in spite of progressic music concepts. Take, for example, the wrong-headed resistance we can still see to Radiohead’s work from Kid A on, a resistance predicated on favoring when they wrote “real songs” or some other absurd stance. It was only with the critical acceptance of Mastodon with the release of their second studio record Leviathan and everything that came after that those doors seemed finally to break at the hinge, burst apart, and disappear.

Resistance to prog is also partly built around shitty behavior and condescending attitudes of some of the people who love it the most. I can’t pretend that there aren’t Dream Theater and Yes listeners who sneer at fans of Beyonce and Ke$ha, or even those who love Peter Gabriel’s work in and out of Genesis but somehow view artists like Kate Bush, Tori Amos and modern figures like Joanna Newsom and Jenny Hval as disconnected from prog largely on the basis of being women who make music like they do. As a fan of progressive rock, I felt the elation of hearing Kanye West build a song around a beloved King Crimson track and do so to create a new derivative work that felt very much in the spirit of that beloved progressive rock classic, only to then see other fans of the style descend into disgusting and unacceptable racism, galled by the fact that a black man dared to sully their beloved music with dirty rap. This in many ways mirrors similar frankly shitty and unacceptable attitudes found within certain sectors of the heavy metal community toward women, people of color, and the queer community, a set of bad faith actions and behaviors sadly mirrored in many spaces beyond even just those two, given that they are pernicious social and personal sins of behavior and ideology rather than something explicitly tied to a form of art and aesthetics.

But we can’t fight these negative behaviors, be they the banal resistance to progressive music as being unhip or the substantially more severe elements of racism and misogyny, merely by attacking them directly. We must also build something new and better. I hope that’s what this is; that is, at least, the aim of things.

***

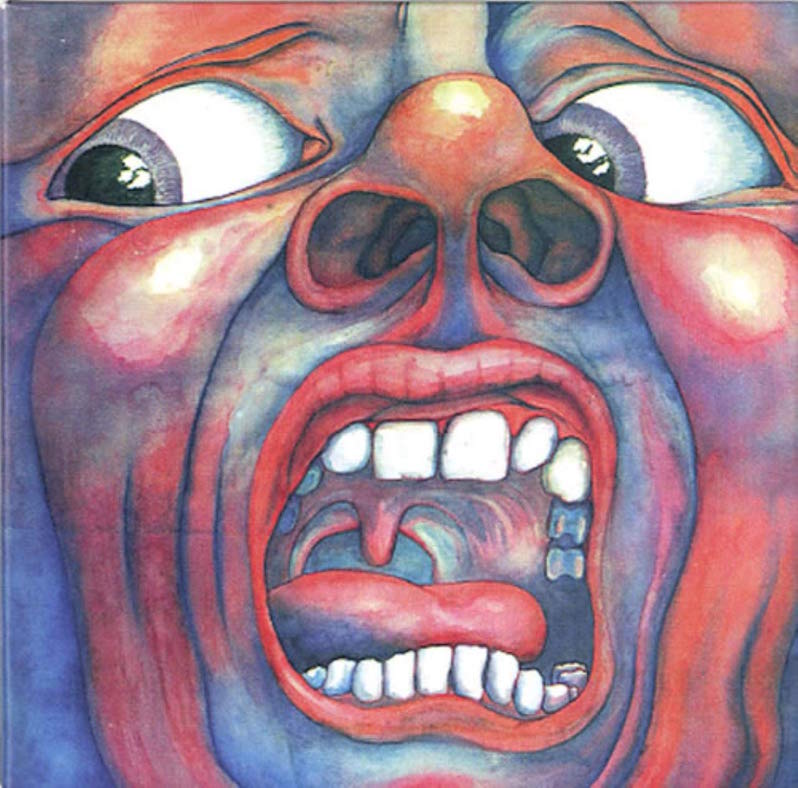

You can’t talk about progressive rock without first talking about In the Court of the Crimson King. This is carved in stone and traced over in blood, an immutable fact of the universe and the spirit of the world. As tedious as perhaps it can be to see the same record written about, named, discussed over and over and over again, it is also the first chapter of the story of progressive rock. In the Court of the Crimson King is to prog what Black Sabbath’s debut is to heavy metal or the Ramones’ debut is to punk, a work that is such a clear and obvious watershed moment that to start anywhere else feels not just wrong but conspicuously evasive. There is an amount of mythologizing (and an amount of self-mythologizing by the band) regarding the record which at times obscures the longest roots of progressive rock but, similar to how Black Sabbath wasn’t the first record to have heavy metal on it and the Ramones would be the first to tell you they weren’t the first band to do the things that made them famous, the material reality of Court being the origin of progressive rock matters less than the myth.

Genres aren’t founded on the back of expanding on good ideas found elsewhere; this is how death metal can balloon in expansion to contain albums and groups that have very achingly little to do with one another on a sonic level. At some point a genre becomes its own space because of a propulsive mythic capacity and not just the material component of a band’s sound or aesthetic. There need not only be a perfect storm of songs and image but that final ineffable gesture, one you can’t deliberately seek but has to be bestowed upon you from somewhere else. This is a foundational thought to Deleuze’s conjoined concepts of the plane of immanence and eruption, something as relatively formless and large-scale as a generalized genreform requiring some otherwise indescribable metaphysical push to break through into the space where things like genres can live. This is a rare occurrence, but given the number of bands and records produced all the time, even a seemingly rare thing happens pretty often, and so in 1969 progressive rock was finally fully born through In the Court of the Crimson King.

Before discussing the history and legacy of the record, it seems fitting to talk about the music. We sometimes develop one of two alternating images of great records. The first is that the songs live very much in their era, embodying that headspace and sonic palette to some exemplary degree. We can see this sensibility in the early work of the Beatles and the Beach Boys, in early Wu-Tang Clan and Nirvana, in John Coltrane and Depeche Mode. There is a tremendous power in not only capturing your era’s general aesthetic sensibilities in whatever genre you happen to be working in but perfecting them, shining the edges smooth so that you can at last crack upon that containing shell and spill out whatever it is that’s trapped inside, that motivating spiritual core that determines the shape of the sounds of your era. Prince’s peak works bleed not the ’80s as a generalized figure but the idealized impossible aesthetic that seemingly everyone was trying to embody, from fashion to music to cocaine usage. The second contrasting form for great records is that of work that seems to erupt outside of the notion of eras entirely. A great example of this would be A Sun That Never Sets by Neurosis, a record with such ineffable emotional heft and power that its sonics seem to not configure to anything related to era. It helps that their influence seemed to peak much later than the release date of those early works of theirs, with even similar avant-doom bands like Earth not really arriving at anything quite the same until years and years later and post-metal, a genre effectively built off the back of their work, not calcifying proper until half a decade later.

In the Court of the Crimson King, curiously, is both. This is dependent on which of several remasters you’ve heard, but effectively any from 2003 onward, the 2019 remix/remaster especially, have sharpened the sonic definition to such a degree that the instrumental tracks sound like they were recorded just yesterday. The album was initially tracked, mixed and released in 1969 and music of that era has a certain quality that even younger fans can pick out in an instant, something specific in the way the microphones and tape recording of the era would drop certain frequencies and make fuzzy and warmly distorted even things that were meant at the time to be pristine. In the Court of the Crimson King surprisingly has none of that, despite being recorded on one-inch tape on an eight-track rig, hardly cutting edge even at the time. This can be credited in part to deft hands on the board in each of its various remixing and remastering stages, with their esteem as a canonical rock band and various touring and re-release efforts over the past decades helping to fill the coffers to acquire the most up-to-date technology to clean up the tapes. But some of the credit has to be handed to the initial production of the record, which saw the band painstakingly layering track after track of Mellotron, flutes, saxes and strings, a battalion of ancillary tracks used to smooth over the cracks and thin-spots in the sonic field so that, even at the time of its release, it sounded gargantuan and monolithic rather than a handful of jazz- and orchestral music-obsessed pop and rock kids cutting an adventurous record.

It helps as well that two of the tracks on the record have little at all to do with the music of their era. Album opener “21st Century Schizoid Man” and album closer “The Court of the Crimson King” form the diptych around which progressive rock was born; if the album were those two tracks alone, its esteem would be no dimmer. The first is a brash metallic banger, a song of seemingly effervescent power which has directly inspired bands from Black Sabbath in the early ’70s to Judas Priest later in the same decade to a group like Mastodon some forty years later. Its blend of free jazz breakdowns, heavy metal histrionics and a distorted bass tone in the verses that would be emulated for countless years to come in metal and prog both. The instrumental breakdown’s playfulness, in which the drums, horns and bass seem to be dancing around one another in a pointillist display of chops while guitarist Robert Fripp weaves a slow-motion overdriven melodic line over top would come to define the instrumentalist sensibilities of a vast majority of prog rock, who heard this and, seeing it was perfect, sought to change nothing. The drumming in particular often gets overlooked when discussing the track, with the firm perpetual roll of notes being a key influence to drummers like Neil Peart and Mike Portnoy in the years to come. A great deal of the instrumental work can broadly be described as fanciful, a fancy brought from joy. It’s perhaps easy to declare music like this pretentious if you are used to people who like it saying they are better than you because you like hardcore and garage rock, but the overdriven blasts of guitar and bass, not to mention the heavy-as-hell verse riff which would go on to inspire a great deal of the first wave of American and British doom metal bands of the ’70s, imply that at least the band don’t share this sentiment. The decisions of arrangement and technicality aren’t made to show off necessarily but instead to paint a particular kind of picture and, more importantly, because it’s simply fun to play. A quick gander at live footage of the era, which thankfully exists, shows the young band absolutely rocking the fuck out with abaddon. This is sincere to them, not a cheap parlor trick. You can smell the passion wicking off of them in sweat-stench.

The album closer is likewise a near-science-fictional example of perpetually timeless music albeit of a different caste. If the opener prefigured heavy metal of the traditional, prog, avant-garde and doom varieties in turns, the closing title track underscored the pomp and grandiosity required for a proper prog epic, effectively birthing a staple of the genre that 50 years hence it still gleefully revels in. From the opening simple drum fill to the panoramic Mellotron strings abetted by simple strummed acoustic guitar to the gentle classical pluck of the acoustic guitar alongside Greg Lake’s immaculate baritone vocal and fluttering flute, it bleeds a sense of imagistic grandeur and visionary scope. There were tracks of similar cant to “Schizoid Man” before it, but “Crimson King” feels much more immediately like it is about to prefigure a seachange in music. The lyrics are surrealist fantasy nonsense, but they manage to perfect this shape. Later groups would attempt to emulate the sensation Peter Sinfield’s fantasy poetry would bring to the group, with some bands like Yes actually finding great success doing it, but most would instead read like bad parodies of this moment. But much like how Black Sabbath and Judas Priest birthed a seemingly endless barrage of bands that loved and emulated but never bested them, King Crimson too were doing something genius here that manages to rise above the general mental image of ’60s music to instead become something constantly refreshed and constantly renovated. The power of ending the album here as well must have been unbearable on its release, a fact we can affirm given the way this album birthed progressive music as we know it when similar longform orchestral/jazz-influenced art rock from the Beatles to the Moody Blues to Procol Harum and more simply did not.

Interestingly, the second and third of five tracks don’t share the era-agnostic sensibilities of the opener and closer, instead feeling like perfected examples of psychedelia and art rock common in the late ’60s. “I Talk To The Wind” and “Epitaph” are a curious set of songs, the former segueing into the latter in an unmarked 15-minute suite that would never see this conjoined form performed live even in sets where both tracks were present. The latter of the two tracks is a grand ballad that seems to sit precisely halfway between the later album closer and the aching orchestral rock early prog experiments of the Moody Blues from Days of Future Past on. The temporal identity of “Epitaph,” when taken on its lonesome, aligns most with whatever was next to it most recently, with proximity to the album closing title track painting it as an epic prog ballad of similar power—much of Opeth’s ballads through their career find themselves indebted to it in one way or another and groups like Camel owing nearly their entire sound to the piece. The way it forms a suite with preceeding track “I Talk To The Wind” grounds it substantially in the very ’60s sounds of proto-progressive rock, in the experiments of the Moodys and the Electric Prunes and early Pink Floyd, who were already underground rock legends in London by the time King Crimson began cutting their record there. This can be chalked up mostly to “I Talk To The Wind” itself, which, uncharacteristically for In the Court of the Crimson King, draws from the art pop of the era, especially Donovan, whose “Get Thy Bearings” was covered frequently by King Crimson and turned into 10-minute improvisations that would later form an integral core of King Crimson’s jazz-rooted live idiom.

And yet this historical analysis, while illuminating certain kernels of truth, would fall somewhat short of the mark. To crack the nut of why “I Talk To The Wind” feels so conspicuously of its time when none of the other tracks do, we have to journey just a little further back to the group Giles, Giles and Fripp. This group, which contained two future members of King Crimson in drummer Michael Giles and (of course) guitarist Robert Fripp, was the initial lineup of what would eventually become King Crimson. They released a single record, titled The Cheerful Insanity of Giles, Giles, and Fripp, which had little impact at the time and forced the band to begin to undergo many rapid changes which would inevitably lead to the jettisoning of bassist and lead vocalist Peter Giles, the adoption of many new members, and a rapid shift in direction and songwriting idiom, prompting them to change their name to King Crimson. (A fuller accounting of that period of Fripp’s early career and songwriting influence is forthcoming.) “I Talk To The Wind” is, incidentally, a cast-off from the failed recordings of that previous group’s aborted second album. The group was a fairly typical acid rock and psychedelic pop group of the time, albeit with slightly more prominent jazz and orchestral influence from Robert Fripp, albeit nowhere near the intensity that would show up even on King Crimson’s debut. The initial recording of “I Talk To The Wind” was made by this previous band under an expanded incarnation that had a dedicated horn player in Ian McDonald (also later to be a founding member of King Crimson) as well as lead vocals by a female singer named Judy Dyble who had, along with a few others, founded Fairport Convention earlier that same year. The song survived those aborted sessions, eventually showing up on King Crimson’s debut, a song that in a single year had seen itself transmogrified from a cutting edge piece of psychedelic pop to a relic of a bygone era, seemingly febrile and senescent compared to the positively science fictional forward thinking music surrounding it. Thankfully, it’s a pleasant tune nonetheless. It is hard, however, to know its history and hear it in the context of the record and not think the album would be better and more synchronous with the piece left off.

This leaves “Moonchild.” It is a mystery of a piece, beginning with a slow and lovely elegiac ballad that evokes the kind of forlorn sense of austerity and beauty that black metal would later become obsessed with, before devolving into a vast and aimless piece of free improvisation, most notable for lack of action than the opposite. This is not meant as a pithy critique—there are literally long stretches of near silence, the performers choosing to create ever-increasing amounts of space until all sense of performance seems to slip away. For most listeners, this choice loses them, feeling like a sudden and stark breakage of momentum in an otherwise near-flawless record. But on the flipside of that, it shows the earliest example of Fripp’s adoration of ambient music which he would later go on to pioneer with his Frippertronics experiments as well as collaborations with ambient pioneer Brian Eno. Experiments need not always be pleasant immediately to be considered successful since their success is governed more by the ground they break than whether that first stab makes best use of it. The drastic slowing of the sense of pace of the album sets up the closing title track quite nicely, making its funereal and dignified pacing feel ever more slow, regal, and pained, adding to the emotional heft of those final moments in sequence.

“Moonchild” perhaps best encapsulates the underside of progressive rock. The standard story of progressive rock is that of rock musicians bored of blues influence, wanting to swap it for something more sophisticated, be it jazz or orchestral music. This is true to a degree, and Fripp himself is one of the people who is loosely quoted in the previous sentiment albeit in a manner that erases his stance that, as white European rock artists, it felt wrong to draw so deeply from a Black American artform like blues compared to other possible spaces, as well as his deep and abiding adoration of players like Jimi Hendrix. But this story ignores something simple but true: progressive rock is simply post-psychedelic music, taking the clear protoforms of prog within the psychedelic pop, rock, folk and proto-metal of the ’60s and pushing it a bit further, whether that be through more structuralism as in the various suites that make up the majority of In the Court of the Crimson King or, with this specific track, drastically expanding the emphasis on improvisation that psychedelic rock had developed.

***

There is an interesting anecdote regarding the Mellotron featured on this record: It was later acquired by Genesis shortly after the mild success of their record Nursery Cryme and it is on the same Mellotron heard on “In the Court of the Crimson King,” “21st Century Schizoid Man” and elsewhere that Genesis wrote and recorded the opening to “Watcher of the Skies”, the opening track off their seminal progressive rock masterpiece Foxtrot.

***

My own personal history with In the Court of the Crimson King is somewhat muted, unfortunately. I have a deep and abiding personal love for the record, obviously, as a fan of both prog in specific and experimental music more generally. The songs are functionally perfect, with only “I Talk to the Wind” and “Moonchild” having slight weakness, albeit ones that diminish in the context of the album as a whole. I had a deep infatuation with the album in high school, often using the opening and closing tracks with friends to show them the kinds of places I was becoming more interested in regarding directions in music. We’d all grown up as friends with parents into classic rock, with my parents having been born in the late ’40s and early ’50s but even the younger edge of parents largely coming of age in the late ’70s to early ’80s, so we’d all grown up with Pink Floyd and the Doors as well as more obscure garage and psychedelic rock like Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Chambers Brothers and 13th Floor Elevators. We all cut our teeth on a combination of Nirvana and Van Halen, early Green Day and Joni Mitchell, Soundgarden and Neil Young. We would later all go on to form punk bands with each other but an approach to punk that wanted to sound more like what Destruction Unit sound like today than perhaps just another Ramones clone. So when I discovered prog and eventually this record, the ideas on it weren’t unspeakably outlandish to my friends. They could follow with what I saw in it and why I, as a young drummer at the time, would prefer to play things that sounded a bit more like In the Court of the Crimson King than Rocket to Russia.

This unfortunately isn’t the King Crimson record that is crowned in my heart. That would be the three-headed beast of Red, Three of a Perfect Pair and The Power to Believe. So why would ( choose to open with a record that I acknowledge is a masterwork but isn’t my most beloved, given the combined personal nature of this column? Two answers, both thankfully brief. The first, as I stated before, is I can’t tell the story of progressive rock from any angle without starting here. This is ground zero. There are other songs and records that came before which can be added to the prog canon, from the closing sidelong suite of Abbey Road by the Beatles being a direct inspiration to numerous prog bands to the aforementioned psychedelic experiments to records by the Nice and more which featured players like a young Keith Emerson. But they only reveal themselves as a part of the prog canon in retrospect; In the Court of the Crimson King is still the lens by which they are seen, revealed as obviously progressive rock largely because we can see how they were the road that led here. But this is the gate, beyond which progressive rock lay. There is no other place to start.

The second reason is because I love King Crimson. I’ve long hounded editors here and elsewhere for the ability to write about the band and it was of my own impetus that in my recent Beginner’s Guide to King Crimson written for this site that I found a way to include comment on every one of their studio records. This is one of the greatest bands in the history of music in my opinion and I know that writing about other records of theirs will come down the line of this column. It is fated; I couldn’t tell the story of progressive rock without discussing those records which are so dear to me and have so sharply impacted the shape of my life and my heart. But no one could tell the story of progressive rock without this one. It’s simply not possible.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

Thank you for the excellent analysis of In the Court of the Crimson King. You’re spot on about Red too. And referencing Kate Bush in the same article? Wow! If you like Prog and like metal, you have to love King Crimson.

Yeah King crimson is a go–

–and that’s why giorno is a girl. P