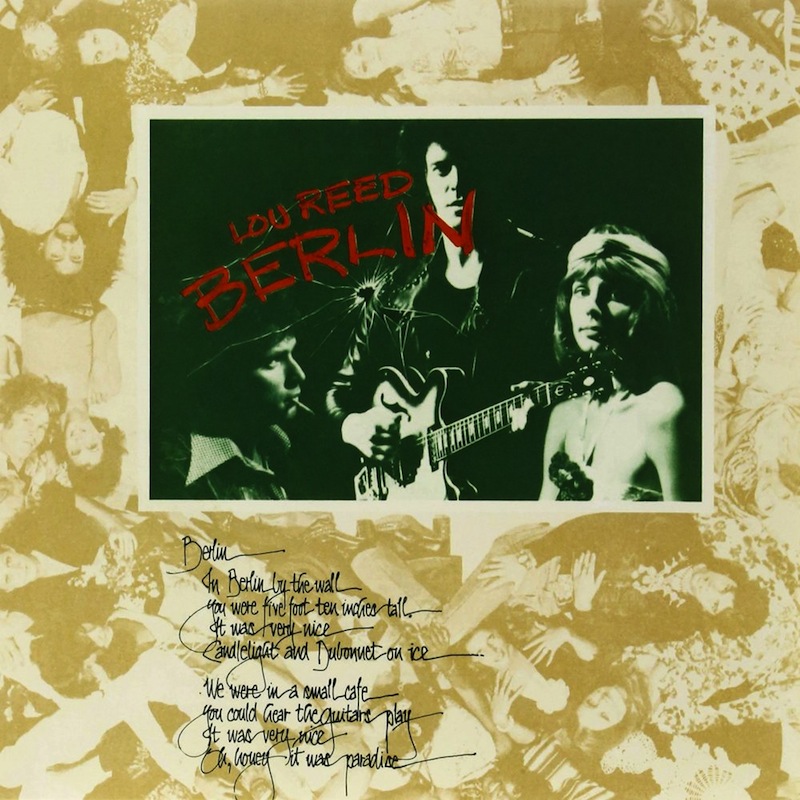

Lou Reed : Berlin

If prompted I will probably say that Berlin is my favorite of Lou Reed‘s solo records. Not only that, but it is, in actuality, the album of his that I listen to most. I mean, what vindictive, somewhat disenchanted romantic does not have a soft spot for accounts of relationships which begin in Berlin, all “Candlelight and Dubonnet on ice,” and end in absolute squalor. By the narrator’s account, his wife becomes a speed-addled tart who makes it not only with her dealer, but with a black Air Force Sergeant, a Welshman from India and a girlfriend from Paris, among others. However, to evince some literal meaning from a careful dissection of the lyrical content is not the proper way to appreciate Berlin. (If there is a proper way to appreciate Berlin—if it is even proper to appreciate Berlin.) It is an album full of despairing accounts of domestic hell accompanied by music that, strangely enough, makes you want to laugh and cry at the same moment. Of course, usually it inspires neither; just a blank stare and the strange confession that you like this record and you do not know why. This is Lou Reed. The delivery of the lyrics is vintage Reed, but the interaction between the lyrics and the music is often disorienting in a new way. Nothing is quite definite here. As a whole Berlin exists in some smoky, profligate den, some side alley of densely reflected neon, full of the deceptions and failures of those who pass through.

Berlin is so nasty at times, pulsates so obviously with actual disgust, with a disturbingly vital antipathy, that to worry about meaning seems silly. Yes, it can be unnerving. Yes, you could take it as some gigantic joke—but if you do I think there is something that you are missing. And that is the problem—I am not quite sure why I enjoy Berlin. In fact, there are times when I absolutely do not enjoy it. It is neither directly affecting in a rhythmic, visceral way, nor quietly contemplatively alluring in the ways that the Velvet Underground could be. There is something blunt about it musically and lyrically, when each is taken separately—the two together, form something altogether esoteric. The train has slipped off the fucking tracks; everything that was taken for granted has gone to hell and now blood is at stake. No wallowing happily in your melancholy with this one, all of you hip cultivated brooders. Berlin will live under your skin, will make actual all of those horrid little possibilities that you have foreseen for yourself but which you won’t acknowledge. I mean, really, someone who is already in a nasty humor could be provoked to uncharacteristic acts of violence by a listen to Berlin.

And, whatever it may be, Berlin is directly affecting—even if I don’t know in what way I am being affected. It is at once infuriating and enticing, a disaster from which I cannot turn away, a musical trip through the question, ‘what if there is only struggle and no redemption’ (save for that which is hallucinated). Berlin is not an album to dwell in, but one to come to terms with; one to accept as exhibiting possibilities, but not as a definite account of how reality is. Is it necessarily true that a trampled husband feels happy when his wife has her kids taken away? Is it a given that he will be relieved, not at all sad, when she kills herself to put an ends to the whole disastrous affair? Is emotion and response necessarily black and white? I for one hope not, because if it is…well it isn’t. I am sticking to that.

So, Lou Reed’s vocals…they are nothing if not ambivalent, off hand, like the scribblings in a pocket notebook of one describing events of which he is not a part. And this is an easy thing to believe until we are reminded, by an I here, a we there, that this is the husband, the masochistic lover, sifting through the wreckage of his relationship. During “The Kids” he recalls, “that miserable rotten slut couldn’t turn anyone away“—of course this guy is pretty fucked up by what he has been through. How quaint. How funny that he seems so indifferent at times. Berlin came out after Reed and his wife had divorced, but I wouldn’t even begin to describe it as autobiography, not that I would know anyway. The pathos at the heart of Berlin, on the other hand, could have come from nowhere else. That this whole account is furnished by one of them, the man, a man who constantly, though not without exception, is portrayed as the victim, is not an accident either. When we are given the alleged perspective of Caroline, through the narrator’s recollections of what she said, the narrator has already been firmly established in his role as unwitting victim. In “Caroline Says I” we see him, yes, as a victim, but also as something of an idiot, a clown who endures his wife’s cruelty and infidelity, still intoxicated with his idea of her as his “Germanic queen.” In the second “Caroline Says” song, he appears as a tyrant through her eyes, someone who beats her, whom she no longer loves, who denies her life beauty, who ‘bums her trip.’ Still, the narrator cannot keep from including the fact that her friends call her Alaska, emphasizing her coolness, her inhumanity. “Somebody else would have broken both of her arms,” muses the narrator as he vows to forget her in Sad Song. And so we have our hero.

Lou Reed’s Berlin is a bleak portrait of human aspiration. Bleak in a particular way, in a way that no other album is. It is full of the washed out colors that populate memories and dreams, the vague images slowly, but never quite, dissolving or taking shape. In the ashes of the relationship lies the ecstasy of its inception. Love, through the reality it brings about, here the relationship between the narrator and Caroline, appears as both an obstruction to freedom and happiness (for her), and a self-destructive intoxicant (for him). Are the characters just fucked up, laughable caricatures, or are they tragic figures on a grander scale, crass allusions to the quixotic nature of romantic love? Somewhere in between the quiet hysteria conjured by the meditation on Caroline’s suicide, “The Bed,” and the comical urgency of the narrator’s inability to keep her from singing on the bar in “Lady Day” lies the answer. Somewhere between laughter and despair lies Berlin, provoking us, prodding us, however unwillingly, to examine the fragile reality of the things that we hold closest.

Similar Albums/Albums Influenced:

Leonard Cohen – Songs of Love and Hate

Leonard Cohen – Songs of Love and Hate

Nick Drake – Pink Moon

Nick Drake – Pink Moon

Iggy Pop – The Idiot

Iggy Pop – The Idiot