Nirvana’s Bleach is still as potent after 30 years

The thought of troves of priceless album masters in an ash heap on Universal Studios’ back lot where an unscathed Building 6197 used to sit is thoroughly gut-wrenching, and although there’s some debate about what exactly was destroyed and what irreplaceable artifacts survived, there’s no question that some percentage of our shared cultural history is gone. Nirvana’s revolutionary Nevermind (but probably not its irascible successor In Utero) is likely among them. One album with definitely intact masters, persistently existing in all of its ramshackle glory, is Nirvana’s 1989 debut album, Bleach, safely harbored at Sub Pop HQ in Seattle since its release 30 years ago on June 15th.

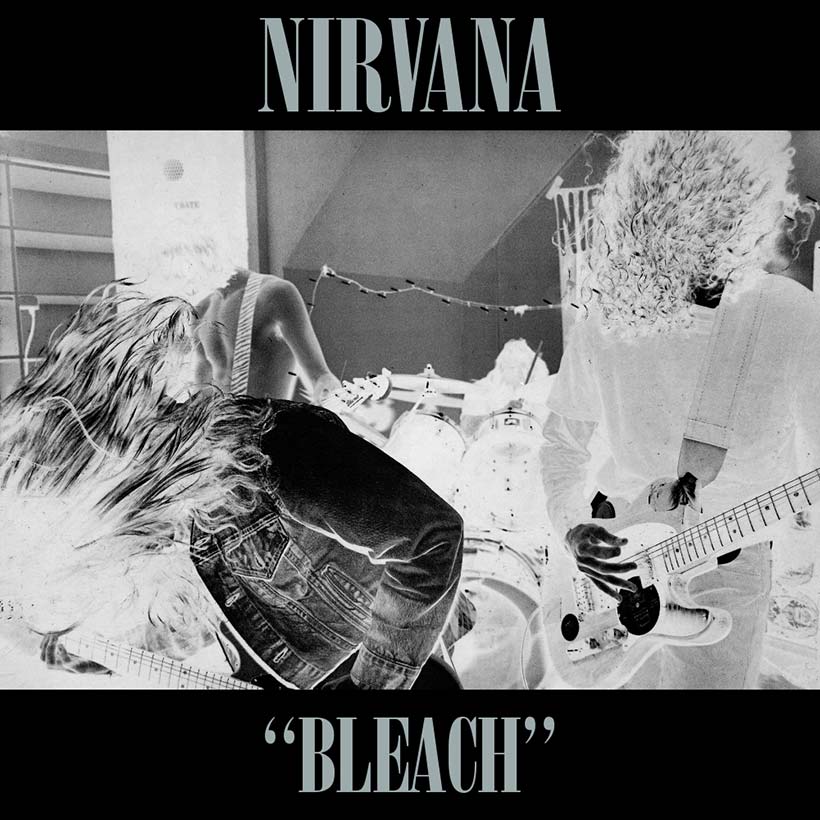

Bleach cost all of $600 to record, and the band didn’t even pay for it themselves. A guitar player and friend, Jason Everman, fronted the money in return for what amounted to an album credit and the chance to play some tour dates with Nirvana. Nobody can confirm for sure if he ever got paid back, but it sounds like probably not. (He’s the one manning the Telecaster on Bleach’s album cover, making the quintessential power trio seem for a minute like a four-piece.)

The cover photo was taken at the Reko Muse art gallery in Olympia, WA by Tracy Marander, the same ex-girlfriend of Kurt Cobain who inspired Bleach’s melodic masterpiece, the anomalous pop cut “About a Girl,” a wildflower of jangly benevolence audaciously blooming amidst a dense crop of ear-splitting grunge.

It was a risky move (within the local Seattle grunge scene, at least) to release a track like that. With the simplicity of its arrangement and lyrical vulnerability, not to mention the tenderness of its refrain, “About a Girl” could just as easily have been transmitted via Michael Stipe’s grainy murmur as Cobain’s granular croon. But he took the risk and put it on the album, and we all know how that turned out.

Cobain planned to name the album Too Many Humans, but changed his mind after seeing an AIDS prevention poster in San Francisco recommending that heroin users “Bleach Your Works” (i.e. needles). Ever thus, Bleach. And as the story goes, most of the lyrics were hurriedly written the night before recording during the 100 mile drive from sleepy lumberjack harborage Aberdeen, Washington to Jack Endino’s Reciprocal Recording in Seattle to record on Christmas Eve, 1988 and again for a few more sessions leading up to New Year’s Eve, for a total of something like 30 hours.

Nirvana’s first sojourn to Reciprocal the prior year resulted in the band’s first demo, earning the attention of Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman who released Nirvana’s debut single (which was also the first of Sub Pop’s limited-pressing Singles Club releases), a full-throated and shredding rendition of “Love Buzz” by Shocking Blue (of “Venus” fame) b/w “Big Cheese” (which was apparently about one of the Sub Pop visionaries) the month prior, showing off Cobain’s warmly acerbic leads and magnetically marbled vocals, and Krist Novoselic’s relentlessly ripping bass. And Dave Grohl wasn’t even in the band yet.

Three of the album tracks—”Floyd the Barber,” “Paper Cuts” and “Downer”—feature drums from a Reciprocal recording session from earlier in the year, when Nirvana was going by the name Ted Ed Fred, with Melvins’ drummer Dale Crover filling in. The remaining tracks were all from the winter 1988 session with Nirvana’s full-time drummer, Chad Channing. It’s hard not to notice Dave Grohl’s absence on Bleach. And although Crover’s drumming certainly slays (and the tracks all work well enough if judged against their contemporaries and not the band’s own pending legendary status), none of those three songs ended up as album standouts.

Andy Griffith slasher fanfic “Floyd, the Barber,” despite the promising lyrical premise, oscillates leadenly between a couple of chords like some underdeveloped sidekick with no discernible motivation; “Paper Cuts”—which depicts the horror story of abused Aberdeen siblings trapped in their parents’ basement with blacked out windows, one of whom was a Cobain acquaintance with one degree of separation overcome by their shared heroin dealer, apparently—is a solid but protracted behemoth gratuitously stretched to four minutes and mired in subterranean turbulence, sounding like they borrowed more than just the drummer from Melvins; and “Downer” is Cobain’s self-described attempt “to be Mr. Black Flag punk-rock guy,” a stylistic holdover from his days in his own punk rock band, Fecal Matter, a few years prior. (On the upside, the lyrics are among the most fleshed out and complex of the album.)

Cobain’s lyrics, which would get more interesting on subsequent releases, were self-admittedly fairly throw-away on Bleach. “It was like I’m pissed off. Don’t know what about. Let’s just scream negative lyrics, and as long as they’re not sexist and don’t get too embarrassing it’ll be okay. I don’t hold any of those lyrics dear to me,” Cobain told Spin in 1993. That’s not hard to believe, as the lyrical repetition can get downright meditative, at times verging on slacker koans.

For example, there are literally four lines repeated throughout the two minute, forty-two second duration of scorching album highlight “School,” an unrelentingly bludgeoning track pulverizing with its elemental riffing and its ripping solos, bluntly transmitting its bleak sentiment. Those four lines of bitching about an enduring social hierarchy, scant as they may be, capture an emotional essence and convey it convincingly, a skill Cobain seems to have excelled at from the beginning.

Unlike later releases, some lyrics land like placeholders until an imagined future in which Cobain might come up with something better. Even so, they’re invaluable flashes of his life in Aberdeen, and they connect Nirvana to the thousands (and eventually millions) of bored and confused suburban teens stuck navigating lives that looked exactly like Cobain’s offhandedly scribbled descriptions.

The album opens with one such number, “Blew,” a glorious introduction to Bleach with its murky ferocity and unbelievably low morass of snarls and sludge (thanks in part to its inadvertent down-tuning to drop C). “Blew,” one of two album singles, lucidly conveys hopelessness in the face of endless potential: “You could do anything” is repeated with unmatched clarity for the last sixth or so of the song while surrounded by an entire album’s worth of relatively garbled stanzas.

A track like the breathlessly glottal “Negative Creep,” which features Cobain wailing over blustery craggy riffs, rings just as true among today’s disaffected and isolated youth as it did to every self-doubting Gen-X slacker who ever suffered through high school and coped in whatever manner made itself available. Cobain understood his audience and gave a tangible shape and meaning to the unarticulated feelings clouding their adolescent headspace—namely their untargeted rage, confusion and aimless frustration. The drugs might be different 30 years later, but the youthful struggles aren’t. And thanks to today’s pharma-fanned opioid inferno circling back and threatening to hook everybody and their father on heroin, the drugs might just be the same after all.

Bleach originally sold fewer than 40,000 copies and didn’t crack the charts, but after the major label release of Nevermind, went on to sell 1.9 million copies in the U.S. and reach the top half of the Billboard 200. In 1989 when Bleach originally appeared, Sub Pop was already releasing some heavyweight grunge: Soundgarden, Mudhoney and Mother Love Bone all had multiple releases out through the label. Nirvana certainly drew influence from Seattle’s grunge scene, especially Melvins, but Bleach also owed a debt to L.A. hardcore punks Black Flag’s B-side sojourn into sludge metal on My War. And Bleach, more than any other Nirvana full-length, is a call back to heavy forbears like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin.

Even so, Nirvana’s debut album stood out from its Seattle grunge contemporaries. Upon its release, NME‘s Edwin Pouncey called it the “biggest, baddest sound that Sub Pop have so far managed to unearth,” and of course it became Sub Pop’s best-selling album ever. Nirvana’s ample hooks throughout the album set them apart, too, and jangly gems like “About a Girl” offer a peek at the caliber of songwriter Cobain was on his way to becoming. His artistic instincts and penchant for gut-punching hooks wouldn’t be fully fleshed out until Nevermind. Nirvana’s Bleach is a snapshot of a band finding themselves within the confines of a particular scene (Seattle) with a particular sound (grunge), building a fan base and making music on a label that necessarily had its own set of expectations.

The zeitgeist-shattering band that would eventually stunt Michael Jackson’s Billboard reign, launch the underground to the cultural pole position and remake popular music in its own disheveled image burst onto the scene far from fully formed in its debut full length, but delivered plenty of tell-tale bright spots at the start of their iconic run. And fortunately, we aren’t marking the 30th anniversary of Too Many Humans by Ted Ed Fred.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.