Our Band Couldn’t Be Your Life: Throbbing Gristle

Our Band Couldn’t Be Your Life is a series that explores bands whose output, operating procedure and reputation fell well outside the norm, often in the realm of the bizarre. Apologies to Michael Azzerad.

A listener’s first encounter with Throbbing Gristle is almost invariably the single most bewildering musical experience one is likely to have. It’s abrasive and foreign, confusing, at times even revolting. If one doesn’t recoil in horror right away, an inevitable flood of questions follows: Is this music? Then, How is this music? Followed by Why is this music? And, finally: Who is this?

Understanding Throbbing Gristle requires more than an appreciation for noise. It requires an embrace of Dadaism and hostile provocation in musical form. While the harsh waves of sound created by Merzbow or Kevin Drumm might come across as unlistenable to those uninitiated in the ways of noise, Throbbing Gristle is a different kind of beast. They were, at varying points, noise, spoken word, performance art, mutant disco, electronic, musique concrete, and just enough pop to keep their albums surprising, and for that matter, repeatedly rewarding.

In that spectrum of genres and approaches, however, Genesis P-Orridge, Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti found a way to make an album as difficult and disorienting as possible, yet did so in a manner that would remain engaging and interesting all the same. Sometimes that meant creating genuine aural nightmares. In other places, it meant placing drones beneath recordings of threatening phone calls. And occasionally it meant making something beautiful. While we all had a good laugh when, in Juno, Ellen Page derided Sonic Youth as being “just noise,” but had Jason Bateman played her “Slug Bait” instead, not only would it have been literally true, he probably would have driven out the teenage surrogate before she ever got the chance to discover his lecherous behavior.

Before getting into the how and the why, it’s best to get acquainted with the who. Throbbing Gristle formed in 1975 in the UK out of a performance art collective called COUM Transmissions, whose primary aims were challenging British conventions, provoking, shocking and seeking reactions from its audience. Though much of what they did was musical, their performances, exhibitions and “happenings” courted controversy at every turn. A flyer with the group’s phallic logo got leader Genesis P-Orridge in some legal trouble, and in 1976, their “Prostitution” exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts led members of Parliament to lash out against the group as “wreckers of civilization.” A bit harsh, perhaps, though being provocative was certainly part of the act, which included pornographic photos, rusty knives, syringes and bloody hair, as well as a stripper and used female hygiene products. What it means was up for debate; the important thing is that it made people uncomfortable.

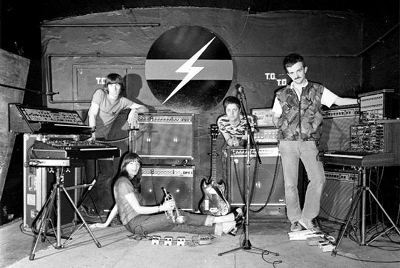

COUM ended in 1976 with a performance by Throbbing Gristle, their first under the name, thus giving the group’s legacy an interesting cyclical progression. Throbbing Gristle was, officially, a band, though the four musicians still essentially operated like performance artists, just with musical instruments instead of nude displays of simulated violence and gross found objects. Not that those elements were necessarily gone — more pornographic stills and other shocking imagery was often a major part of their performances. The music, however, still made for the strangest and most disorienting part of Throbbing Gristle’s live presence. It wasn’t pretty or melodic in any conventional sense, certainly not at first, anyhow. The general make-up of Throbbing Gristle’s sound was pre-recorded tape recordings, distorted drones, a variety of strange effects and spoken word, though that was only a jumping off point for more radical experiments and ultimately, more structured compositions. As Cosey Fanni Tutti told Vice magazine, anything was fair game as long as it wasn’t commercial.

Industrial Music for Industrial People

Throbbing Gristle released four full-length albums in their five years as a band, all on their label, Industrial. However, it’s the first three that are most compelling, and their debut, Second Annual Report, could not in any way, shape or form be construed as “commercial.” The title is oddly straightforward, as if the band were issuing financial statements, and packaged in a nondescript white sleeve with the title and description of the album, which contains live recordings from their first year as a band (hence the annual “report”). One might not necessarily get the full scope of Throbbing Gristle’s viscerally confrontational live performances on this 1977 recording, which hits its 35th anniversary this year, but there’s enough of a sense of the group’s bizarre antics to make it a noteworthy, even compelling piece of art.

Recorded via cassette in as muddy and grubby a manner as possible, Second Annual Report sounds awful by design, and the abysmal fidelity only speaks to the absurdist nature of the band. That said, it does lend the album a charmingly harrowing quality. It’s an uncomfortable listen for a variety of reasons. Side A features three versions of “Slug Bait” and four versions of “Maggot Death,” and the second side is taken up entirely by the 20-minute “After Cease to Exist.” Picking apart which element of Report is its most squirm-worthy is an arbitrary task; when everything sounds so wrong, why choose? But the prize goes to “Slug Bait,” which in its three separate parts is, respectively, a discordant dirge from the perspective of a murderer, a mixture of opera samples and vacuum-cleaner guitar, and an interview with an actual murderer. “Maggot Death” is more of a real song, a truly noisy song, though in its `Live at Brighton’ permutation, consists of only P-Orridge shouting insults at the audience. Not much happens in “After Cease to Exist,” despite it being so long, and after a mindfuck like the first act, maybe it’s best that it doesn’t.

While TG were using the Industrial name for their label long before “industrial” as a genre received any kind of recognition, the band’s second album, D.O.A.: The Third and Final Report, is a much more concrete progenitor of the wave of industrial that followed in the ’80s. It is, simultaneously, more and less musical than Second Annual Report, featuring a variety of more fully fleshed out songs, as well as several tracks of electronic noises, recorded voices and other oddities. One of those oddities, “I.B.M.,” is essentially a series of bleeps and gurgles, undercut with Christopherson’s characteristic bass drones, while “United,” which in another incarnation is actually a fairly accessible single, is merely 16 seconds of rapidly escalating fast-forward screech. “Valley of the Shadow of Death” is a series of recorded conversations juxtaposed with ambient sound, though what these people are actually talking about is a bit foreign. It’s a tad mysterious given the lo-fi quality of the chatter. Could be barroom chums, could be criminal conspiracy. For as strange and seemingly non-musical these tracks are, they’re curiously alluring in spite of the high cost of entry — after those noisy signals in “I.B.M.”, more nigh-musical elements begin to take shape, if never fully congealing, and the sheer confusion of “Valley” gives it a reason for repeat visits, to futilely attempt to decode whatever’s happening in these found discussions.

D.O.A., despite its many confounding pieces, is nonetheless the stage at which actual songs began to have more importance for Throbbing Gristle, which no doubt contributes to its being the go-to TG album for many, including the editors of “1001 Albums to Hear Before You Die.” These structured pieces come sporadically, but with heavy impact. “Hit By a Rock” is closer to Suicide than more noise-based industrial acts like Einsturzende Neubauten, while the quasi-title track, “Dead on Arrival,” is the group’s own take on no wave disco, a pulsing beat carrying through a progression of squeals, whooshes and thuds. By normal standards, “Dead on Arrival” would be utterly confusing, but in Throbbing Gristle’s world, it’s what passes for accessible. Then there are the “ballads,” if one can describe them as such: “Weeping,” a gentle art-pop song with Genesis P-Orridge’s detached, disturbing croon guiding the way, and “Hometime,” an ambient piece blended with children’s dialogue, more innocent and simple than those of “Valley of the Shadow of Death,” but still as confusing.

Of the many odd directions that D.O.A. takes, two tracks at the center of the album comprise its most essential elements — “AB/7A” and “Hamburger Lady.” “AB/7A” was, in 1978, Throbbing Gristle’s prettiest, most approachable song. In fact, it remains such, for the simple fact that rhythm and melody take precedence over anything else. Clanging percussion and detached voices drift in and out, thus connecting it to their other songs, but the gorgeous krautrock melody is what makes it stand out as a song that can be played for those not quite ready to dive into TG’s most depraved moments. “Hamburger Lady,” however, is one of those depraved moments, perhaps the most depraved. Depending on who you ask, this is the most terrifying song ever written, and with good reason. Electronic sounds wheeze like the escalator to hell, effects-treated vocals moan in the background like lost souls sucked into the underworld, and Genesis narrates a description of a burn victim. It’s ultimately one of the simplest pieces here, but each small part is engineered to repulse in a very tangible way. That it’s so masterfully performed is what makes it so harrowing.

Persuasion

Throbbing Gristle’s progression toward more, um, “conventional” songs continued with the third album in their celebrated trilogy, 20 Jazz Funk Greats. The quartet’s strongest album on the whole, Greats never betrays the group’s ideal of anything-goes anti-commercial sound mangling. They just do it in a way that comes off, ultimately, as more listener friendly, as antithetical as that seems to their whole way of thinking, sometimes, even in the choice of album cover, which seems actually commercial, until you realize they’re standing on Beachy Head, a popular venue for suicide. In the first spin of the title track, there’s a clear divergence from the chaotic anarchy of D.O.A. and Second Annual Report. It has beats, it kind of has melody, it seems to go in some kind of direction. It’s bizarre and twisted, as expected, but not altogether unpleasant. It’s almost, almost, a jam. Deeper into the album, there are some actual, legitimate jams, but it takes some detours to get there. The band does ambient drones on “Beachy Head,” noisy sputtering industrial beats on “Still Walking,” and exotic, psychedelic mood noir on “Tanith.”

Somewhere around the middle of the record, much like on D.O.A., Throbbing Gristle unpacks their heaviest hitters. In a haze of drugged out wooziness, “Convincing People” is a lurching, stomping beast that calls out for energy and outrage. Nowhere is the group’s newfound embrace of danceability and melody more explicit than on “Hot on the Heels of Love,” their sleek, Moroder-esque disco single in which Cosey plays a breathy, robotic diva among sexy Eurosynth sounds. That’s right, I said “sexy” in the context of a Throbbing Gristle song, as well as “danceable,” which seems even more wrong after a couple years of noise and antagonism. That can’t so much be said of “Persuasion,” a two-note glimpse of horrific sexual depravity that returns, in a way, to the fucked up Throbbing Gristle that might have never considered making a song as fun and funky as “Hot on the Heels of Love.” That’s the beauty of 20 Jazz Funk Greats — there’s room for both disgusting abrasion and accessible songwriting, which come together perfectly on closer “Six Six Sixties,” which is dark, punk rock evil, creepy without being bludgeoning, and abrasive without being exceptionally loud.

The band released one more album after 20 Jazz Funk Greats, 1980’s Heathen Earth, which in a way married the live aesthetic of Second Annual Report with the more updated beat styles of Jazz Funk. It’s not as compelling as its predecessors, though still an interesting companion piece, though from that point on, the individual members of Throbbing Gristle, who broke up in 1981, took on completely different directions. Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti, who had since become a couple, began making synth-pop as Chris & Cosey. Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and Genesis P-Orridge formed Psychic TV, a revolving door industrial/neofolk collective with P-Orridge as the only permanent member, as Christopherson later joined Coil with PTV collaborator John Balance. Most of these were far more “pop” than Throbbing Gristle, though still a bit twisted, as none of the musicians could ever really move away from making music to make people squirm.

In 2008, Throbbing Gristle reformed, performing Second Annual Report in its entirety, dubbed in reference to its anniversary as The Thirty-Second Annual Report, and performed at Coachella a year later. They re-launched Industrial Records and reissued and remastered their catalog in 2011, though at this point, Throbbing Gristle Mk. II was already over. Christopherson had died the year before, and P-Orridge, two years after the death of his significant other Lady Jaye (with whom he had undergone a series of body modifications in the pursuit of becoming a single pandrogynous entity), had retired from touring and performing. Chris & Cosey, meanwhile, remained together as both life partners and bandmates, changing their name in the ’00s to Carter Tutti.

Throbbing Gristle was the farthest thing from normal in their time together, and time hasn’t made their music seem any more conventional or easy to decipher. And even their weirdest individual projects following the break-up of the group don’t seem nearly as wildly experimental. There were almost no boundaries to Throbbing Gristle’s music, and in revisiting their albums more than 30 years after being released, their source of curiosity and intrigue is boundless as well.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.