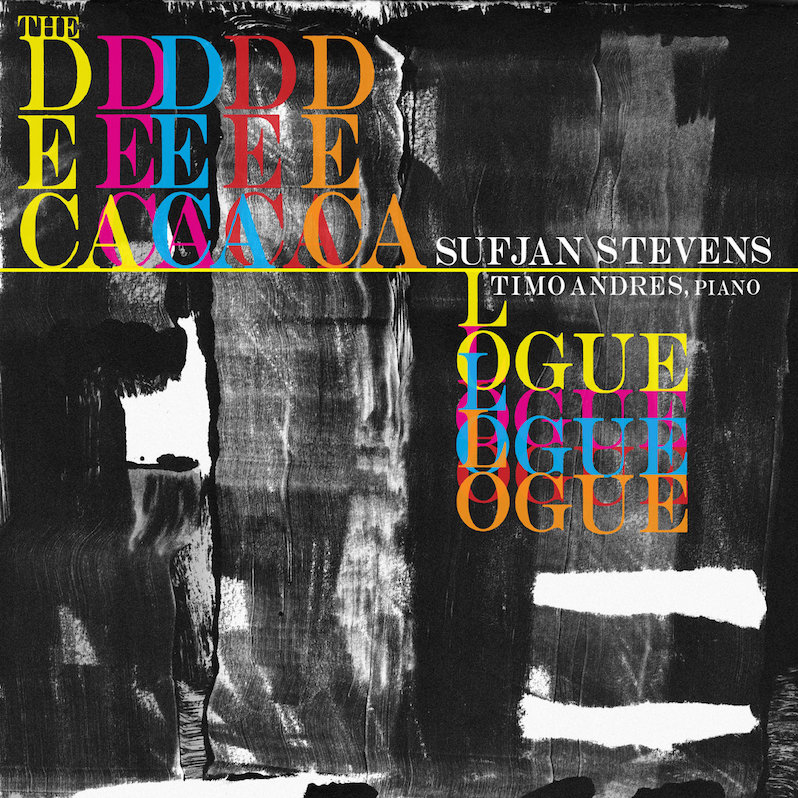

Sufjan Stevens & Timo Andres : The Decalogue

It is time for a critical reevaluation on Sufjan Stevens and what precisely he brings to the table of contemporary music. His critical reception, thankfully, has been positive since the beginning, first respecting him as a strikingly clever songwriter and strong musical performer within the at-times mawkish and overly-twee world of indie music of the early 2000s before his shift roughly ten years ago now to more avant-garde and experimental works. Yet despite the number of contemporary classical song cycles and ballet scores under his belt, our social and critical image of Sufjan Stevens still seems to hover most prominently around the image he produced around the period of Seven Swans through to his ill-fated 50 states series. It is easier to imagine him in a sleeveless shirt with a fashionless hat tilted sideways on his head, banjo and ukelele slung half-ironically across each shoulder, than it is to imagine him hard at work behind a piano with sheet music and pen by his side.

This isn’t to say that we should discount his more explicitly populist material or disavow his roots as an artist that performed in small clubs and coffeeshops and toured with pop groups. If anything, this grounds him far more with art music composers of the past who, despite our current social image of them, were largely the equivalent of pop stars of their day, producing songs of drinking and sex and revelry alongside their more serious and stern works. This balance of playfulness and depth is not one that is new to the world of music, but while we tend to have this loose association with Sufjan Stevens, that association seems largely predicated on the fact that his songs at their most zany and quirky still manage to, shockingly, actually satisfy where a lot of indie rock and pop stalwarts of the time of his debut feel now to be shockingly dated and ill-equipped to face the shape of the world in modern times.

Which brings us to The Decalogue, the fourth ballet score composed by Sufjan Stevens in conjunction with young superstar ballet choreographer and director Justin Peck but the first to be issued a wide commercial release. This is notably the 20th ballet that Justin Peck has commissioned and had performed during his tenure as director of the New York City Ballet, the preeminent ballet of the entire hemisphere, having only noteworthy cultural rivals in Europe and, on occasion, South America. The relevance this has to the piece of music is that of submission; here on The Decalogue, Stevens shows a remarkable sense of selflessness in composition, creating pieces for solo piano that, while beautiful on their own, are clearly intended to be the backdrop to the work of another performer. This leaves a slightly weak experience of the music on its lonesome, with the pieces often being substantially more elliptical than the typically emotionally forthright Sufjan Stevens you may likely be more familiar with, but also underscores their success as a ballet score.

In keeping with this subject of submission, we see that even despite these being solo piano pieces and Stevens himself being, among other things, an accomplished piano player, he chooses not to be the performing artist for the record, instead tapping Timo Andres, a noted contemporary classical composer and pianist who currently works with famed art music label Nonesuch Records. This choice feels like a deliberate one, one meant to elide Stevens’ presence and the image he might bring to bear on these pieces, instead choosing to foreground a label more closely associated with contemporary opera and ballet recordings, a player known in that world, producing a score for a major contemporary choreographer. It would be easy for a figure like Sufjan Stevens, who already has the adoration of so many, to have crafted this moment to bask in the praise of his genius; instead, he steps aside, foregrounding the world and the work, a rarity in music and art.

These pieces, uniformly of brief length and striking a sense of Romantic piano composition a la Liszt or Chopin, have that sense of an emotional curlicue, winding up within each other while offering little in the way of a clear emotional in-road to understanding them. The title of the suite and the ballet from which they are drawn, The Decalogues, refers to the ten commandments but, unlike our expectation, they are not tilted toward the known ten commandments but an undisclosed replacement. Apparently, even on witnessing the ballet these pieces accompany don’t elaborate a great deal; they are striking and evocative, but point to no clear parallels to murder or theft or lust. The uniforms are practice garb, the stage unadorned, and then these bare piano pieces swirling about the dancers. It is clearly meant for ponderance and physicality, a rerouting of rumination into daily embodied living, but one that at times is more elliptical than it is pretty.

In terms of how The Decalogue stacks against Stevens’ other distributed art music, it is perhaps his weakest. The BQE was a riveting piece of electronically-accompanied classical music that hardly anyone expected to come from Sufjan Stevens and seemed to blow the doors off of his creativity, still standing as one of his best works. The Enjoy Your Rabbit / Run Rabbit Run diptych song cycle about the Chinese zodiac, one fully electronic and the other a classical reinterpretation, is perhaps his most heady and illuminative. Planetarium was a strikingly directed work, the first sign of Stevens’ ability to submit himself to the subject of his art in a way it’s easy to doubt many of his other indie music compatriots would find themselves capable of doing. And his volumes of Christmas show a sense of both playfulness and inventiveness to his music as well as the beautiful sincerity of his faith in a way that’s moving even to non-theistic hearts. In comparison, The Decalogue is a record of pretty music clearly missing its other half. For some ballet or opera scores, it’s not terribly difficult to enjoy their successes even without staging; Stravinsky, for example, is more often associated with the music sans accompaniment that with for most people. But here the pieces seem to clearly suffer, being beautiful and enigmatic but ultimately a bit too thin and unforgiving to open up fully.

Still, despite the sense of weakness to the overall coherence of these pieces, or at least their ability to give up some sort of road to understanding, it is hard not to respect them both on a musical and artistic level. It’s easy to close your eyes and imagine hardened limbs extending and curling in time with the fluttering of piano keys, the deliberateness of the cant of the head and the turn of the hips. Played next to Seven Swans, this feels like a completely different composer, one who seems to only becoming more strident, ambitious and accomplished with time rather than burning out and resolving himself to recycling easy indie rock overtures like, say, The Decemberists. On its own, The Decalogue is a pretty but short-lived album, one that you will likely move past quite quickly. As a supplement to his body of work, it feels like a strong argument for a critical reinterpretation of who Sufjan Stevens is as a composer, how we imagine him, and how we approach his work going forward.

Similar Albums:

Sufjan Stevens/Bryce Dessner/Nico Muhly – Planetarium

Sufjan Stevens/Bryce Dessner/Nico Muhly – Planetarium

Alarm Will Sound/Donnacha Dennehy – The Hunger

Alarm Will Sound/Donnacha Dennehy – The Hunger

Beth Gibbons and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra – Henryk Górecki: Symphony No. 3

Beth Gibbons and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra – Henryk Górecki: Symphony No. 3

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.