We are all haunted. There is a space between the solidity of earth, the outside world and our actions in it, and the secret gardens that generate the self. In this middle space, the empty cosmic void in which twin planets of earth and moon are suspended, memories accrete like dust, forming surreal networks of drifting matter, rings and meteors, planetoids and irregular clusters. So much of the music I love and have loved sits within this space for me, progressing beyond the merely phenomenological domain of experience into the world of memory and richness. It grabs onto these clusters fragments of memory, digs through the refuse and stones that orbit in ellipses around me to form not just dead connections but new ways of seeing and processing that which I’ve already experienced. These are the fundaments of so much of the world of art and why we love it; not that it merely exists as entertainment but that it penetrates deeper, reorders our experiences via its own schema to reveal us to ourselves as though we were art hung in our own interior galleries. I listened to a song by Prince and began pondering the limits of my own gender; I listened to a song by Shamir and broke down crying because the image became clear. This is what art is.

Yet there is a moon beyond space, an object not of accretion, not of experience, but of the experiencing-self itself. There is the obvious and nearly-cheap comment here, its light and dark side, the literal name of Pink Floyd‘s Dark Side of the Moon, and yes that’s in part on purpose, but there’s more meat to the bone of this metaphor than just that. It is rare for art to capture this deepest interior in part because it cannot occur by penetration. Penetrating this moon of the psyche, to borrow Qabbalistic imagery of the Earth as the living body and the moon as the domain of the mind itself, the gateway to the divine interior, requires being outside of the moon first. It must be an object that exists outside of the self, is not-self, which then integrates into the self. But by the nature of its innate alienation from the self, this integration can never be fully completed; it always remains part of that middle space, the experiencing memorial selfhood, the thing between our psyche and our external selves, the world itself. And so: art often does not change this inner selfhood but capture it, less like a photograph and more like encountering words spoken by your own tongue, the uncanny sensation that a spacio-temporally displaced version of yourself left some artifact for you to discover. In the curling and confused tangles of time and the self, they are keys we leave for our own doors, the knots growing tighter and stranger as years pass.

***

I grew up in a musical house. Music was my father’s primary succor in a confusing life. He was born in the ’50s to parents who lived through the second world war, had family that served in it and were wounded by it, themselves children of parents who had served in the first world war. The psychopathy of American culture at the time did not allow remittance for people with bipolar disorder, people on the spectrum, the artistic spirit encapsulated; and so, when war came in Vietnam, my father, knowing he was to be drafted, volunteered for that nihilistic evil shit-show of a war, forced to commit and witness the crimes of America meted out on yet another innocent group of people defending their homes and came back scarred for it. He leaned on his father, my grandfather, for solace. How do you carry the weight of war? What you have seen, what you have done, the guilt and shame and confusion, the sense that none of it was worthwhile and you’ve come back permanently stained and ugly? His father’s answer was simple: you lock it away. You never speak of it. Especially to the women, the children. The real sacrifice of the soldier is not dying in the field; it is returning home having lived, having done things, seen things, and knowing that for the mental and emotional well-being of others, they have to stay hidden forever, no matter what it does to you. My father, having been beaten mercilessly by my grandfather who was half-mad in his own twisted pain from war, a pain passed on to him by his own infinitely more demonic father, back and back, found this answer untenable. So his night flight, his private Jerusalem, New York City, to be a studio and gigging musician. To escape. He’d played on The Soupy Sales Show in a band in his teens; it wasn’t an unattainable dream.

Some works of art shock us, emerging seemingly from the ether. There is a magical quality to them, like some brilliant silver door catty-corner to space and time rotates into view and deposits this brilliant egg from another place.

My mother’s flight into music as solace was mercifully less dramatic. She too was a child of the same era, opposing my father’s path by joining the Students for a Democratic Society to oppose the unjust war. Bravely, she got an abortion in the late ’60s before it was fully legal, without the knowledge of her deeply Catholic mother, having to make her own secret night flight to New York for the procedure. (She never let me or my brother forget the sanctity of this decision, how controlling her own body is what allowed her and thus us to have the life we live, that this by its nature must be inalienable. I love you, Mom.) She was likewise a child of the ’50s and ’60s, someone who lost her own father at 19 near Christmas, who wrapped herself in the musical and literary culture of her years to carry her through. Her own undiagnosed autism, only getting properly certified after my own, with her in her early 60s at the time, retroactively made sense of this comforting cocoon of art, the vehicle by which the world is made sensible. But at the time, it was pure experience.

As a result, there was always music playing in the house when my brother and I were growing up, from classical and Baroque music to jazz-fusion to pop to funk and Motown and soul to heavy metal and grunge to classic rock. It was a blessed childhood in that respect; there were brutalities and difficulties, as all childhoods have, but music was the balm by which the four of us were unified and understood each other. Pink Floyd was a favorite of both of my parents but especially my father; he told me once of how, returning from Vietnam to the years of Meddle and the build-up to The Dark Side of the Moon, they became in part the soundtrack to his own confused flight from the hell of his parents’ home, the confusion of his experience in the midst of war and all the things he could not erase. Years later, he would be diagnosed with bipolar disorder and from that seed so too would I. That fraught and terrified core seemed mirrored for him. He bought the records as they came out: first Dark Side, then Wish You Were Here, Animals, and finally The Wall, a run so perfect he stopped following the band entirely, finding everything he needed in those four. He only had two beyond those: Meddle, which contained some of his favorite tracks by the band, and Ummagumma, an album of unremitting terror and madness in its avant-garde cacophony, especially the mysterious and blood-curdling “Careful With That Axe, Eugene”. (My brother and I later would, of course, dig into the rest.)

***

Some works of art shock us, emerging seemingly from the ether. There is a magical quality to them, like some brilliant silver door catty-corner to space and time rotates into view and deposits this brilliant egg from another place. But there are other works which feel almost the opposite, like they are inevitabilities, inscribed in stone since nearly the dawn of time, awaiting a moment of enunciation. The Dark Side of the Moon is the latter. Pink Floyd’s promise was never in question. From their early days in the London underground in the mid-’60s, being one of the preeminent bands that played a quiet massive influence on the burgeoning mainstream psychedelic sound, they were marked for greatness. They recorded their debut The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in Abbey Road Studios, one door down from The Beatles as they were cutting Sgt. Pepper, an album whose sequenced but still song-oriented macro-structure can be felt on Dark Side in abundance.

The Barrett years were always a place of mad experimentation, inaugurating one of the first recorded noise tracks with some of the live bootlegs of “Interstellar Overdrive” and its phantasmic and profound middle section, sometimes extended for 20 or more minutes. The released material tended to stay in the more typical arrangements however, despite the curiosity of the chord choices and melodic movement. It was only with the addition of David Gilmour on guitar and additional vocals in the lead-up to A Saucerful of Secrets that the group began to let shine what to live audiences understood about their brilliance. The years between Saucer—the first record to properly display that the promise recognized by The Beatles when George Martin let them sit and watch “Lovely Rita” be assembled in the studio wasn’t a fluke—and Dark Side were striated with bewildering experiments. They cut the soundtracks to short films and features (the Zabriskie Point soundtrack being a highlight); they recorded noise and soundscape suites with kitchen implements and animal sounds, replicating and deepening the legends of the Beach Boys that had been circulating and their mad genius leader; they released a shocking and avant-garde set of solo recordings under the band name, spanning everything from scalding progressive heavy metal to twee pop to orchestral material. Their crowning opus of a record prior to Dark Side featured a song sung entirely by a dog (the album opener and closer of Meddle are rightly a bit more well-known than the strange “Seamus”).

Three projects in particular paved the way most directly to Dark Side. First was “Echoes,” the closing track of previous record Meddle and the group’s sole 20-minute piece (at least sequenced as one track). The legend goes that they were approached by Stanley Kubrick to provide a score for the “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” psychedelic closing sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the band, sensing a keen opportunity, seized on it, retooling a piece originally called “Nothing,” “Son of Nothing,” and “Return of the Son of Nothing” to more tightly fit the filmed material. Famously, Kubrick did in fact have feelers out for contemporary music to score the film before deciding ultimately to try to license the recordings of the specific pieces of orchestral music he had used to pace the shots themselves, presumably leaving some stranded, if any were in progress at the time.

A conflicting report has the group watching the film and dreaming up making an accompanying piece to that final section, finding it both inspiring and fitting their mood. Neither story, it turns out, has much truth to it, or at least much truth disclosed by sources that are reputable. This germinal notion is likely one of the key elements that later mutated into the similar myth of the synchronization of Dark Side with The Wizard of Oz, another phantasm of the mind that fits with the level of sonic perfectionism Alan Parsons, their engineer at the time, would likely have pursued. Regardless, “Echoes” became their first masterwork of the macro-scale progressive world, extending beyond the realms of the psychedelic and providing clear arrangement and compositional framework for future epics and album-length arrangements from the group.

The second was a conjoined set of pieces performed live known as “The Man” and “The Journey.” Bootlegs of these suites abound and are easy to find, showing up recently on extended box set editions of some of their classic records. These were suites being assembled starting in the very late-’60s into the early ’70s, often performed in their entirety one after the other at live shows. They are mythic arcs, one charting a common man’s day (a recurring theme for psychedelic and progressive bands at the time, notably in the Moody Blues’ Days of Future Passed), and the other a reconfigured Ur-mythic tale, a sojourn without much in the way of details. Musically and thematically, they laid the groundwork for the next three albums, containing elements that would occur on songs within The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here and Animals, including elements of their overarching themes. The sense of inevitability was mounting by this point; it was clear that the band, who brimmed with promise from their beginning, were preparing to unleash a set of masterworks.

The third and final work on the ascent toward The Dark Side of the Moon and that mythic golden age was their concert film Live at Pompeii. A concert film without compare, it’s one of the few to stand toe-to-toe with Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense and come out on top as a superior film, a rare honor. The band plays in the austere and glowering empty amphitheater of dead Pompeii, surrounded only by stone, marble, the ghosts of the slaughtered dead. Shots of the audience are replaced by murals of skulls and skeletons, memento mori, action shots of magma floes, the sight of the sky crouching to cover them like a blanket as they played. The group stands in the center of the circle, just the four of them, Barrett now long-departed to his madness that would keep him for his entire life, a haunting figure in this place of ancient haunting. They play their most harrowing material: “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun,” “Be Careful With That Axe, Eugene,” “One of These Days.” A sense of menace pervades. Darkness, humiliation, threat: the imperium in sternness. Then, like euphoria: “Echoes.” Like a stone thrown into the shimmering pools of the past, ripples at your ankles. The song’s story of the sea now transforms into a story of escaping the savage volcano by boats, by water, as a fish, as a bird. That some of the footage was actually shot in Paris and comped together didn’t matter. They had made at last a concert film that didn’t feel like a documentary as much as a film itself, a statement. The pyramids on the poster within The Dark Side of the Moon conjoin these two, monuments of the mystic heft of antiquity; in the theatrical release of the concert film, they included in-studio footage of the making of The Dark Side of the Moon, a second conjoining.

And so they were prepared to give birth to something monstrous in its perfection, often regarded as perhaps the greatest progressive rock record of all time if not one of the greatest rock records period (and certainly one of the best of the decade).

***

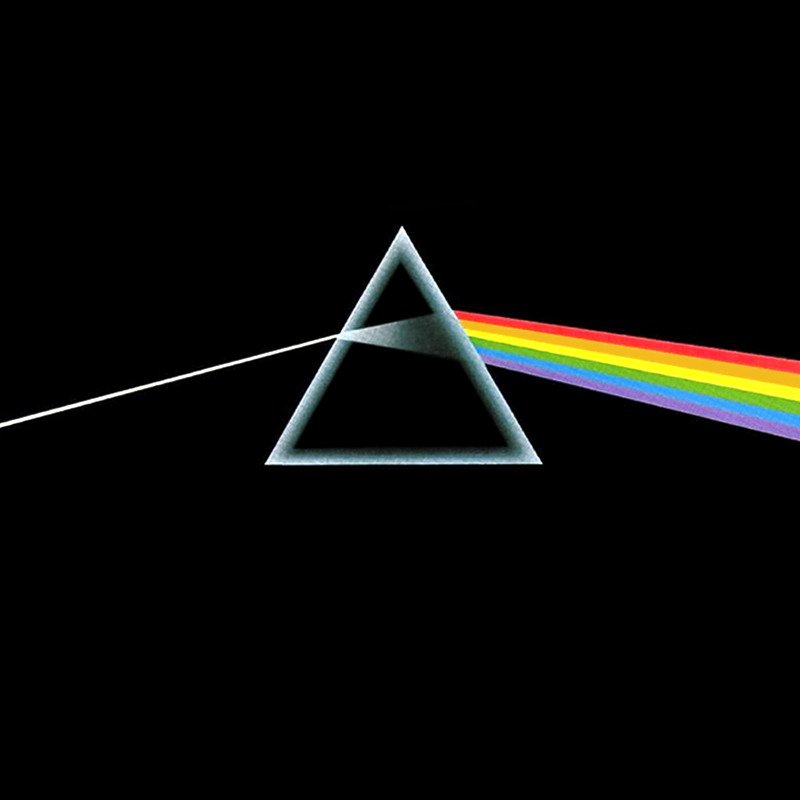

My father would play Pink Floyd so loud it would literally rattle the house. This was our bonding exercise: Dark Side blaring with such intensity the pictures hung on the walls were clattering in their frames, the sleeve open in my lap as I sat cross-legged on the floor, turning it over and over, tracing the rainbow with my eyes as it turned from white light to heartbeat to light again. He still had the poster of the pyramids, the stickers. I remember being struck immediately, as young as five or six, poring over those lyrics and listening to that music. An uncanny trembling overtook me: this is my future. I was fixated even as a child on “Time,” a song which choked me near to death as I lay in bed at night thinking about how my grandfather died before I was born, how my step-grandfather had just passed. He was, what, 80 or so years older than me? So that’s how long we get. And I couldn’t even remember the first few years of my life at all. Suddenly time seemed to tick fast and slow, seconds wasted and eternal all at once. I would stare at the clock and hyperventilate, counting down to the freedom of adulthood at the same rate I was counting down to the eternity of the grave. I couldn’t decide if I wanted the clock to speed up or slow down; agnostic to my pain, it ticked on the same rate regardless.

“The Great Gig In the Sky,” the euphoric soul and R&B psychedelic choral piece, is the soundtrack of a soul entering heaven. My little eyes would close: Was this what my grandfather had experienced? Is this what awaited me? As a young child, still religious, little terrified me more than (ironically) angels and the eternity of heaven. Contemplating the unending expanses of white, worshipful faces and conjoined limbs, petrified me more than I could say, rendered me catatonic. “Money” and its loping 7/4 groove was my first taste of odd time-signatures, a feature which would come to dominate almost all I loved. Lyrically, however, it described the hell I was born into, the nouveau riche sentimentality of my parents, ’90s white couture evolving from Reagan ’80s political shifts. My mother and father had given up any sense of radicality, save for a tenderness toward gay rights; the pursuit of money guided them in those days, taking them from the home for days and weeks at a time, leaving me stranded, isolated. My brother, electrified with his own traumatic terror, would beat the ever loving fuck out of me, force me into silence, all while neighbors and family friends would attend dinner parties and aperitifs to schmooze with my family, all for want of money. And I know it was just for money: the minute my dad got fired, got sick, the minute our family became to upper middle-class eyes ignoble and embarrassing, the visits stopped. People wouldn’t even call. A brutal lesson in the coldness of capitalism and how it ruins the heart.

And then there was “Us and Them,” a story about war. Roger Waters’ father was lost in World War II; haunted by this fact, Waters would return to it again and again, haunted by the nihilism of that loss, the nihilism of all war, which kills and injures so many beyond its finite borders and battlefields. He would wonder, as he did in that song, how generals in abstract rooms could make the decision that would kill so many soldiers of both sides and so, so many more civilians, all the families that would be left fucked up and ruined, all the people that would make it home from the war worse be it by physical or mental decay. He would wonder how his family and his own life might have been different if his dad had been spared. I did too. Even as a child, I knew of my dad’s service and knew too how it contributed to his alcoholism, his manic and psychotic fits, the things that would rob him of his career and eventually his life. Even now in my mid-30s, I can’t shake the feeling that it was the Vietnam war that killed my father, another victim of Kissinger in the latter years of that conflict deliberately extended so as to make sure Johnson couldn’t get re-elected. How those cycles of the cynicism of war repeat ever and ever again. The pain and rage of the populace transformed into a general and a politician’s capricious moving of pieces on a map, representing over two million trapped in an open-air apartheid prison, chewed alive by white phosphorous just as their parents and their parents before them war. How stupid, how evil, how cruel.

But of all these, it is the finale of “Any Colour You Like,” “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse” that struck my heart like an arrow. They develop as a single suite, emerging from the psychedelic outro of “Us and Them,” a burgeoning meditation textually on the loss of sanity of Syd Barrett, their beloved bandleader in the early days of the group. Diegetically within the record it serves a modified function, that of describing madness writ large, the way the scattering anxieties cataloged over the course of the record’s span work to eventually unravel the mind. It always seemed inevitable to me, madness and mental illness. There were too many stories in my family, from my great aunt losing her mind following the death of her beloved in World War II to the derangements on my father’s side in the days after war to the hellish Hickman family curse, our name for the specific type of existential depression that has savaged so many of my kin. I was a child first hearing this and already it seemed prophetic, not a warning but a promise.

What shocks me about this is not so much the strength of that impression, its immediacy, but how all of it came true. I would experience breaking madness, like the foaming of the sea slashing and shattering against black rocks on the shore, and from that madness I would experience poverty and hunger. Death consciousness gnaws at me still, making me feel always like both the tortoise and the hare, having accomplished nothing in my life with so little left to do anything of note. I have a sneaking suspicion I will die young, close to 60, like my father; it is not uncommon to fear we will die when our fathers do. War mutilated my family decades before it even properly started and the loss of that mutilation has never gone away. The Dark Side of the Moon did not feel like a prophecy: it has instead been a constancy. Some art changes the way you view the world, but this record has had the ineffable power of capturing perfectly and instantly the anxiety, paranoia and dread that has lurked in my heart since childhood and never gone away. That I would grow up to chase after extreme metal is no shock to me; it is in part a coded attempt to recapture the sense of impossible dread this record still stokes in me.

It has pervaded my life. When my brother and I were at each other’s throats, sometimes literally, with knives, this was a record that would soothe us both, bong smoke and couch cushions quelling that boiling complex siblings’ hate we had for each other. In college, my friend Josh and I would listen to this in the pitch black of his dorm, eyes closed, in the year before both of our lives exploded apart. I have purchased every remaster of the record, a habit I picked up from my father who did the same; its minute changes feel to me less like alterations of a work of art and more revelations of this work that told me the shape of myself before I even was. In truth, I don’t even love this album like art. Instead, like 2001: A Space Odyssey or Jorges Luis Borges or “The Starry Night,” it feels like a fragment of myself, eternal and unchanging, that I was meant to discover out there. Some art arrives and shocks us with the quality of its craft. Other art becomes the soundtrack to our lives, sinks in by repetition to the sinews of memory. But this record is different. It is bizarrely exactly what its title promises: the moon of the psyche and its darkness, not the things that happen to you but the things that are inside of you. Given that it is also one of the highest selling records of all time, my relationship to this record is not unique. The beauty and the terror has struck millions. It is not often that so many are so, so right.

When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.