U2 played it frustratingly safe on All That You Can’t Leave Behind

It was fated, I suppose. As much as a great deal of this series has been devoted to a critical reevaluation of U2‘s work, especially that of the mid- to late-’90s predicated on the quality and experimentalism shown in their earliest days, this was inevitably a series about U2. The most frustrating aspect of the band, especially for those of us who count ourselves by and large fans of the body of work, is that at the end of the day the features of the band everyone knows as the most tedious do in fact exist. All That You Can’t Leave Behind, despite these warnings, is not the worst record you will ever hear in your life, but it is certainly the beginning of the precise U2isms that became so tiresome over the past two decades.

As mentioned in the previous chapter covering Pop and U2’s first remix record, a compilation which spawned a shockingly robust and decades-long Pink Floyd-sized effort by fans to catalog alternate versions, b-sides, experimental one-offs, outtakes and of course further remixes of the band, the group emerged from this period enervated rather than energized. According to the band, Pop was a half-formed entity which over the course of touring revealed its weaknesses, especially compared to the more solidly-composed material of the band’s primary body up to that point. Growing criticism of their increasingly bipolar band depiction, half hypercynicism and half sincere experimental futurism, urged them to retreat backward to the sonic safety of more conservative shores.

For years, this has been the dominant narrative of this record, one underpinned seemingly by the initial singles from the record. “Beautiful Day” certainly strikes closer to the earlier days of the band than the Zooropa industrial experiments and dance music digressions. “Stuck in a Moment That You Can’t Get Out Of” and “Walk On” feel like rehashes of Rattle and Hum soul and The Joshua Tree spiritualism respectively. “Elevation” comes across like one of the failed hard rock tunes of the group’s earliest records; its remix crafted for the Tomb Raider film only doubles down on the radio rockisms of the track. The issue with this image is it focuses on broad strokes rather than the fine-grain details. The former would turn this record into precisely the kind of record that is easy to dismiss, the clumsy myth that anti-U2 types cling to when discussing this band as a whole. But it is the latter that drives the frustration with this record, with intriguing Eno and Lanois-led experiments offering glimpses of a more excited record that could have been had only the band remained brave.

First is the choice of producers. In any other band’s hands, turning to the efforts of Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois would be seen as a pivot toward experimental urges. Given the history of the band, with that duo having handled the production duties of three of their most acclaimed records in The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby, one would feel well-grounded in assuming based on the names on the label that this record would return to the curious mixture of abstract expressionism and melodic hymnals, the group’s evocative and silently influential proto-post-rock and ethereal pop inclinations born against sincere and radiant spiritualism. However, this view ignores the history of U2, where while Steve Lillywhite was foundational in creating their earliest and most direct sound, Eno and Lanois were then the catalyst to the second phase of U2’s essential character. By the ’90s, however, U2 had moved on, embracing contemporary industrial and dance music producers in part to push the band further outside of their comfort zone. It is precisely because this combination of artist and producers had created highly lauded records that had become iconic for their sound that makes even a presumed experimentalism present here a kind of conservative retreat. It is well within the grasp of figures like Eno and Lanois to push U2 into territories they had never entered before. But, based on those broadest strokes and the statements of intent by the band, it did not appear that this was what was destined for this record.

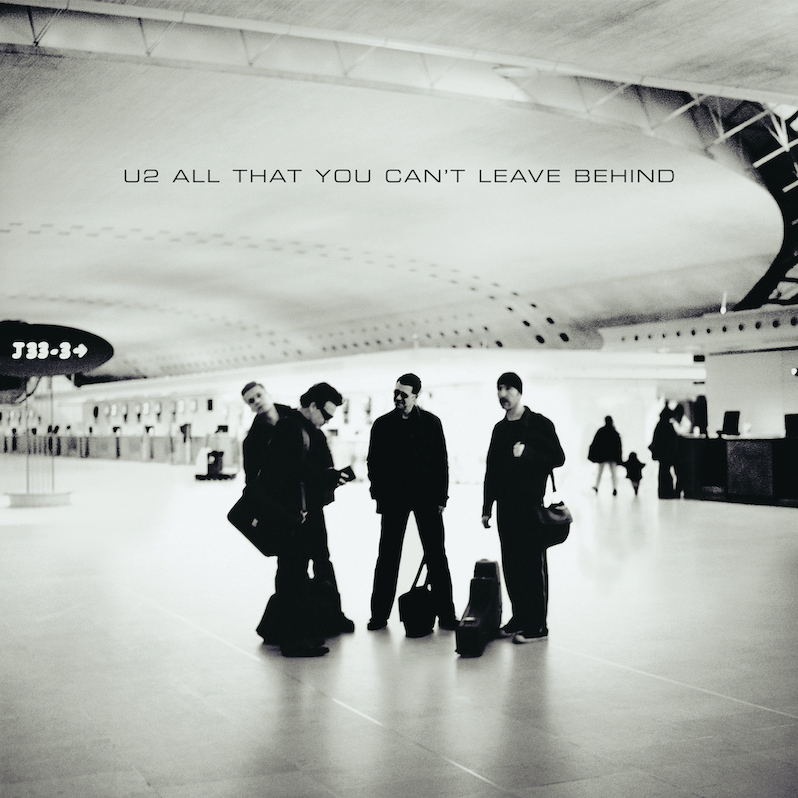

The second set of fine details that emerges to complicate the frustrations of All That You Can’t Leave Behind are the granular features of its singles. “Beautiful Day,” its opening track and lead single, is underpinned by layers of Mellotrons, synth strings, a dance beat, and gradually accumulating guitars ranging from the throbbing and direct bass line, the melodic lead guitar and the textural atmospheric sweeps. It strikes less as a return to the pure formalism of a radio pop rock song and more to the sublimated conservative edge of Achtung Baby, a record otherwise touted as an experimental turn for the group. That earlier record of the group, while featuring some pivots from what U2 themselves were known for, still amounted largely to experiments carried out by other more daring groups years earlier. What U2 brought to the table in those days was more a two-fold attack of catchy melodies and a shift in the perceived image of an otherwise already-iconic band. But by 2000 with the release of “Beautiful Day” on video channels like VH1 and MTV, that allure had already been busted; the image of Clayton and Mullen with their spiked hair, the Edge with his goatee and knit cap and Bono with his helmet of sleek black hair, full body black leathers and wraparound sunglasses felt less like an image of the future and more like a deliberate return to something that had only been groundbreaking a decade prior on the fluke of these specific four being more associated with cowboy hats and vests and bared chests than the darkness of early ’90s industrialism.

Likewise “Elevation,” in its album version, hews closer to what one might expect from a Pop b-side. Its main body is driven by a sensuous and groovy ’60s mod bassline with burbling electronics pinging like radars around the group. A clean guitar emerges, sounding more like something from psych/prog greats Love than dead-eyed hard rock. Even Bono seems to be deliberately delivering a psych-rock pastiche of nonsense images meant more to be catching and amorphous than explicit and self-explicating. The fault here, as in “Beautiful Day,” is less a lack of quality in the material and more a lack of boldness. You can almost hear the forbidden layers of sequencers and drum machines, the post-Radiohead jabs of incoherent distorted guitars. That the song took off on radio airplay makes sense; there is a hook and a compelling sense of groove and rhythm on display. That the remix shifted more toward the banal and everpresent retro rockisms of the era doubles down on the worst tendencies of the track, not its best. But even this remix feels at least like a somewhat vain attempt to remain in contact with some lingering sense of danger present on Zooropa, an element the group seemed ironically simultaneously impelled to destroy.

“Stuck in a Moment You Can’t Get Out” reads at first like an attempt to recapture the same ill-fated attempts toward real soul and country music present on Rattle and Hum. It isn’t that white performers simply have no access to the necessary elements to pull off this kind of music; see the Rolling Stones, for example, as a group that was embraced by precisely the rich legacy of Black music they are sometimes seen as stealing from. The issue, at least in the ’80s, was that the sincere reverence on the part of U2 somehow blinded them to grasping precisely how to feel and sit inside the music, to make it feel sincere and from the heart and body rather than a deliberate affectation and construction. This cut, shockingly, fares much better; Bono, the Edge and Clayton practical sound like they’re at church, pulling melodies and swing from their heart of hearts. The issue, seemingly small before ballooning in size, is that Mullen, their drummer, seemingly has no real sense of the pulse and swing of this kind of music. He chops away at the hi-hats like a metronome, lacking the sense of pocket and sense of body that this kind of music requires. Drums are a funny thing; to the ear, they may sound near identical, but the feel, this indescribable but deeply felt component, lingers like an aura. For something like this, you should be able to almost see the drummer clenching his eyes closed, mouth twisting into that half-grimace that comes from when you are wrenching a sense of beauty from your heart. Soul music demands a specific kind of lilt to the shuffle, one absent here. It feels instead like an affectation. And, for soul, the drummer sounding painfully irrevocably white quickly spoils the whole endeavor.

“Walk On” meanwhile is a hybrid figure, evoking at once the chiming brightness of the guitars from The Joshua Tree, the loose alternative atmospheres of Achtung Baby and intermittent dance music pulse borrowed from Pop. It is perhaps the song most done wrong by the perception of All That You Can’t Leave Behind, ironically the song that gives the record its title. Suddenly here it feels less like a retreat and more like a culmination, a returning home. The experiments of previous records, whether they went too far in their homes or not, are brought into union. The band members seem to each be in their strengths here, Mullen delivering a rolling rock ‘n’ roll beat that feels like it’s pinched from the Stones, Clayton sinking deep into a melodic bassline, the Edge being allowed to color and elaborate from the fringes like a minimalist Johnny Marr while Bono delivers a soulful croon.

The problem isn’t within the song but without; in the wake of 9/11, it was the song that U2 lifted up as the patriotic anthem of their second home and it was around this song that the jingoist fervor that would be stoked into decades of imperial aggression and millions of casualties would be formed for those that should have known better. In previous decades, efforts like the Vietnam war would at least have been resisted by demagogues, disregarding temporarily Kurt Vonnegut’s painfully accurate view of art protest in the way of the war machine. For a brief moment after 9/11, even those who should have known better suddenly viewed the Taliban as responsible for the efforts of a Saudi-funded terrorist group based out of other nations and would soon find themselves cheering for blood and vengeance under the name of justice, all under the image of Bono clutching a billowing American flag as the song played. It was an attempt at unity on the part of the band, not unlike their similar efforts in the 80s protesting war. But here it turned sour in their hands, and its a sourness that is hard to wash fully away from the song. For those able, however, a testament to the album buried beneath the image suddenly emerges.

Off the back of those singles, all four of which are clustered right at the beginning, suddenly All That You Can’t Leave Behind opens up into a shockingly different shape. “Kite,” the first song following the singles, is an atmospheric rock song that feels at its worst feels like a weaker Joshua Tree cast off from the second side and at its best like an admirable throwback. “In A Little While” is a harmless but charming soul pop song grounded in a shockingly modern hip-hop drum beat. “Wild Honey” is a song in turns confounding and joyful, both presented from a lyrical vantage point of youth fully escaped from the members by this point but presented in a breezy California acoustic pop shell whose songcraft is sharp enough to excuse the confusion. The album continues in this mold, delivering unambitious but modernly textured pop-rock, all to varying degrees of success. Moment to moment, it’s hard to describe it as painful or frustrating; any given track inserted into another album would conjure at the very worst a shrug.

What stings is how you can hear in almost every instance the more wild and untamed song that could have been. A younger U2 might have taken these songs, as high quality as they are, and pushed them into different shapes, either more abrasive or more grand or more dappled. The minimalism and concreteness found here is not the true shape of maturity but instead that of fear. It is the sound of band that grew scared of shots in the dark they felt hadn’t landed their mark, shots which in retrospect are some of the most exciting and bold of their career. This album would be far less frustrating if the material was simply limp and lifeless in its entirety, like a collection of Imagine Dragons songs or Coldplay at their worst or any number of the other U2 imitators that drove the image of the band into the dirt. Little fails here but little excels either and always you can hear just a few additions and production tweaks away a better song. Bad songs aren’t failures. Good songs that are not brought to fruition are. Failure requires a potential success to be squandered. That’s why at root this material strikes such a sour note. Worse songs would come, with their very next record containing easily their worst song of their career, but here instead there is only uncomfortable failure that didn’t have to be.

This sense is furthered by one of the benefits both of U2’s extensive b-side and studio castoff compilation campaigns issued through the 2000s as well as the current vogue of deluxe boxset remasters of records containing tracks cut from the record. The qualitative difference between the material that was cut and that which made the record is vast, suspiciously so for a U2 record. The first record of the group to have extensive material carved from it was The Joshua Tree, a record which in some stages of development was intended as a double record by some members of the band and thus had lengthy writing sessions. While the final shape of that record is largely unimpeachable save perhaps a few moments of side two, we are benefited with a lush set of incredible b-sides, from the sketch finished in 2007 known as “Wave of Sorrow (Birdland)” (perhaps their greatest recorded song) to “Luminous Times” to the studio version of “Silver and Gold.” One of its songs, “Beautiful Ghost/Introduction to Songs of Experience” would be the first hint at the desire to produce material loosely tracking William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, a project which would come to fruition 30 years later. Rattle and Hum saw most of its sketches released as part of the record proper while Achtung Baby saw a slate of demos refurbished and expanded for the strikingly experimental Zooropa. This had always been the counter to the band, where the studio records would largely cut the image they wished to foreground, one of world-conquering pop and rock, but with additional material which betrayed the experimentalist urges that Eno and Lanois saw in the first place.

The issue with All That You Can’t Leave Behind is that where on previous records some of these experiments would share space on the main record proper as a lead to guide the curious to more adventurous material from the band, here that link was severed. A track like “The Ground Beneath Her Feet,” initially released as part of the Million Dollar Hotel soundtrack and included on some copies of Leave as a bonus track, sounds miles beyond that which made it onto the record proper. Here we see the proper inheritor to the throne of Achtung Baby, where experimental gestures and pop acumen merge into a seamless alloy. “Levitate” melds the euphoric post-dance music elements of the Pop years with all its gentle electronicisms with a clear and simple melody seemingly plucked from the days of October. “Stateless” perhaps is the most compelling of all the cast off tracks, hinged on a post-Chris Isaak atmospheric country shimmer, sounding at times like a more grounded Palm Dates cut married to a ruminative and gently wise political lyric from Bono. “Always” presents a more equal-footed return to the hymnals and heartstrings of peak ’80s U2, draped in the unique guitar shimmer that would later come to bear on shoegaze and the like despite the quiet resistance of those scenes sometimes to acknowledge U2’s influence over their works.

Which is to say that despite the image the band presented in interviews during the production of the record, rejecting the cynicism that began in the days of Achtung Baby, blaming their own reactionary conservative sonic retreat on having struck too boldly in the past decade, they clearly still had the capacity to pursue these ends gainfully. Sure, we have to admit that some of the cast-off tracks were rightly left off the record, such as the musically excellent ode to pregnancy that reads quite, um, different called “Big Girls Are Best” to the flummoxing Johnny Cash cover turned into a white reggae vamp in “Don’t Take Your Guns To Town”, a track so bad it has to be heard to be believed. But beyond these rightful exclusions, material more befitting not only of U2’s rightfully storied collaborations with Eno and Lanois but also more in keeping and honoring their legacy is found in the vaults.

Most shockingly, it’s material that is quite simply better. It makes the main record feel in its shadow more like a post-Austin Powers swinging London pastiche premised on U2 rejecting perhaps the most exciting decade of their career. But even of these types of tracks, b-sides such as “Love You Like Mad” finally deliver precisely the kind of layered and textured sonic palette that strikes as legitimately psychedelic and compelling rather than a cowardly half-hearted attempt. It is hard in the wake of this not to feel a kind of resentment against Achtung Baby, one perhaps only half-earned, given that it was off of the back of the inward image the band struck that led us inevitably to this moment. This in turn shows clear the dangers of overly cynical and reactionary aesthetic positioning for any artist. The vaults have revealed that U2 was not in fact inherently boomerizing, producing material comparable to lukewarm Coldplay covers before that band as well would turn sloppy and sour. Instead the band snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. It was precisely this moment, one we see often in the former punk’s derisive sneering at the youth where they embrace the corporate world to reject their peers, that U2 assumed the image of eminent cornballs that most know them as today. What’s most tragic is it did not have to be.

Curiously, the recent rerelease of the record, aside from punching up the mix in a manner which feels finally skewed more toward hi-fi listeners than pop radio mixes, also reveals a number of remixes of the tracks released as singles, including ones produced with Melon collaborators Paul Oakenfold and Paul van Dyk. Going over each of these remixes track by track is unnecessary and would be grandiloquent, but the general arc revealed by them is that the band wasn’t even fully committed to their self-statement of rejecting the ’90s and its sonic fruits for the band. Sure, this material was relegated to b-sides of singles, soundtrack releases, compilations and the like, but the fact is the material was still produced. Further, it addresses precisely the lingering faint issues I stated previously about the otherwise solid set of singles from this record. Each remix takes a different approach, but all of them feel rooted in the sense that these are inherently good compositions that simple needed a couple more layers of details, crossrhythms and energetic boosts to really capture that vast, universe-sized and heart-devouring capabilities of U2 at their best.

This is the beautiful potentiality within failure. U2 may have initially produced a record that, despite wowing some critics at the time, has revealed itself to be the most tentative of their studio records. But the intervening years have seen them release more than enough material, be it in remixes, remasters or cut tracks, that one could reconstruct a far different, far more exciting and far more respectful record which both embraces the bands legacy through the ’80s and ’90s, nods to their influences from the ’60s and ’70s and points toward, ironically, the precise bright future the band would eventually reclaim in the 2000s and 2010s. But the dark edge to this, that the best of U2 in this period would come from rescuing their better nature from the band’s own bad decisions, would sadly become the predominant narrative of this era. The structuralism present in U2’s career thus far begins to fall apart; Leave and How To Disarm An Atomic Bomb certainly form a diptych, but the band themselves abandoned its path by No Line on the Horizon, itself part of a planned diptych that was likewise abandoned for a staggered double album. If anything, Leave begins the beginning of their most frustrating trilogy, one made up of a series of two albums, then one album, then two, each marked precisely by the tendency toward self-sabotage lingering here. But, thankfully, in many respects this record marks the nadir of the group sonically, and one of only two great hurdles to overcome when discussing the positive merits of the group to unbelievers. Thank god for those b-sides and remixes, right?

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

I have never read such psychobabble ballix in all my life….