U2 tapped into a well of light on The Unforgettable Fire

The curiosity of U2’s mythic image is that we imagine them perpetually as enormous, filling arenas and blaring from car radios, blasted across our televisions and newspapers as much as they fill up our phones with unbidden new material. Elements of that image took seed in the group’s first trilogy; their native polemicist nature, for instance, had been a portion of the band’s identity since the days of crafting their debut Boy from the ashes of their EP Three had been immortalized on tape. Increasingly bombastic performances and material, evolving naturally in the explosive fervor of hit singles “New Year’s Day” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, culminated in the explosive and fervent statement that was Under A Blood Red Sky, capturing their passionate and dreamlike performance at Red Rocks, Bono and the band clad in nothing but fire, smoke and the heaving mysticism of the American west, a sky and stone as big as their ambition. It seems easy to draw a line straight from here to the world-conquering power of “Pride (In The Name Of Love)”, a song which prefigured their universe-consuming The Joshua Tree and everything that came after.

The problem with this mythic image of U2 is it both wrongly ascribes a certain character to The Unforgettable Fire as a studio document as much as it likewise misunderstands the locus of the band up until this point. It is true in absolute terms that Fire was the beginning of a new trilogy of the band, one which saw the group become larger than the whole of the world, but this was incidental to what the records were in and unto themselves. One of the key elements when approaching The Unforgettable Fire that is revealed quite quickly is the roots of U2 within not just post-punk broadly but goth music more specifically. In retrospect, this seems quite obvious; the dreamlike fires of the red stones of Colorado seem not just like immediately telling precursors to the imageset of this record but likewise to be a primal primitivism more closely associated with Siouxsie Sioux or perhaps the Cure, appending a rich imagism of the magical world to the previous spare and industrialized clattering the band had plucked from Joy Division. The Cure had notably by this time just completed their own first great trilogy, the goth rock power of Seventeen Seconds into Faith and finally the apocalypsis of Pornography, while Siouxsie and the Banshees had already laid to tape their masterwork Juju, the two groups even briefly fusing with The Cure mastermind Robert Smith’s joining of the latter. Too often in discussing U2, we pluck them out of history as opposed to remembering them in conjunction with their peers; it is always in post-punk thunder and magic that we must remember the group.

Just like those previous goth rock nobilities, U2 would likewise turn away from the tortured darkness of their earliest material with their 1984 record to instead tap into a well of light. For the Banshees and the Cure, this would inevitably be read as a reinvention or reconsideration; for U2, the resolute light gleaming across the tracks contained on The Unforgettable Fire feel at once the same, a redefinition of the aesthetic and imagistic aims of the group, as much as they were prefigured covertly in their previous work. The Unforgettable Fire most notably serves as an immediate reclamation of notions the band had explored on October, their otherwise weakest member of their initial trilogy, clutching from that murky pool the intense spiritual fervor and haziness. The strongest elements of Boy and War had formed the firm outer shell that U2 themselves would return to inquisitively in the later forms of this trilogy but, by and large, The Unforgettable Fire is instead indebted to the fragmented and half-dissolved weeping post-punk euphoria and spiritual ekstasis flirted with on tracks like “Gloria” (or, to a degree, War‘s similar closer “40”).

This shape almost never came to be. The band mutually parted ways with Steve Lillywhite, each having felt their work together had at that time drawn satisfactorily to a close. The list of producers pursued before settling on the final pair of Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois provide a series of intriguing potentialities the band could have taken at this venture. First was Conny Plank, a producer who previously had worked with the krautrock groups Can and Kraftwerk as well as the early shifting art pop of Ultravox. One can almost hear the ideas present that must have drawn them to Plank; the final atmospheric maneuvers of The Unforgettable Fire certainly feel in moments like a brighter-hued post-punk recapitulation of motorik rock, shimmering abstract waves and shrapnel of guitar abetted by the moto perpetuo of the rhythm section. This certainly fits the inevitably European and arty direction the band pursued, Kraftwerk and their cold electronics acting as the unifying between U2 and David Bowie, a musical figure who made a similar curious turn from world-conquering bombastic rock to more esoteric and krautrock-influenced European art music. Next was Rhett Davies, producer of Roxy Music, a group notable for having featured a young Brian Eno before his departure to the avant-garde realms of his solo career. Roxy under singer Bryan Ferry’s leadership had not shied away from the avant-garde either, though their approach was more integrated and sleek than the brute abstractionism of Eno’s own work, offering a sophisticated but still arthouse potentiality. A third option considered was Jimmy Iovine, best known for Bruce Springsteen’s art-Americana trilogy of Born to Run, Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River. The American producer had worked with U2 on their fiery live record Under A Blood Red Sky; he was ultimately turned down only just before recording was to begin.

Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois inevitably landed the gig. Initially, however, the position was extended solely to Eno. The Edge was a massive fan of Eno’s work both in group settings, solo, and especially behind the producer’s chair, having crucially contributed in shaping the aforementioned Bowie trilogy. The influence of that trilogy upon U2 (and, more generally, all of music) can’t be overstated; Bowie and Eno’s fusion of the then-dying progressive rock with the arthouse avant-garde of Europe and the raw pop of American soul music all abutted against the jagged Europeanism of figures like Bertolt Brecht and Jacques Brel. Particularly of note here was the playing of Robert Fripp of King Crimson both on the Bowie album “Heroes” and the Eno record Another Green World, playing recapitulated in the Fripp/Eno ambient records. These showcased a densely layered and shimmering approach to the electric guitar that was commensurate with The Edge’s own playing, tapping into the post-punk impulse of The Edge borrowed from groups like Joy Division and their peers to create cathedrals of diaphanous sound, all within the hands of a single player. Eno was initially going to turn down the offer, with stories conflicting about whether he was put off by the bombast and bleeding sincerity of the group or simply on the verge of retirement at the time. In his stead, he offered his engineer Daniel Lanois, who had worked with him previously on a piece for the soundtrack to David Lynch’s adaptation of Dune. It was a combination of Lanois and meetings with the group that convinced Eno to inevitably join into the project as well, compelled by the way the group viewed their work from less ego-driven positions and more group-minded arrangement, contributions weighed by their contribution to mood and ambiance rather than places for showmanship.

The duo of Eno and Lanois provided U2 with a balanced pair to develop their material, Eno pushing the group into more abstract and avant-garde territory while Lanois provided an engineer-minded earthiness, keeping at least one element of any given piece rooted to the ground while others were freed to depart and explore. We are quick often in retrospect to credit much of this period of the band’s work to Eno. While there is certainly truth in this assertion to a degree (see the increasingly hazy sketchbook-like approach to lyricism employed here by Bono, hewing closer to the cut-up method fractalized poetry of David Bowie than his own previous post-Springsteen strict narrativism), this thought betrays both the band’s own developments toward this direction on their own as well as Lanois’ own keen contributions. The previous list of potential producers already betrays that this directionality was more or less decided by the group, whether consciously or not, erring on the side of arthouse European producers responsible for the driven punkish approach to prog found in krautrock or else the arthouse Americana of peak Springsteen. Likewise the fact that Lanois would later follow up The Unforgettable Fire by coproducing Peter Gabriel’s So indicates a sophisticated understanding of the necessities for prog-pop to succeed and a fusion of the arthouse and the accessible that Eno had notably fallen on the other side of with Bowie’s trilogy, a superlatively satisfying set of records that yielded between them only a single chart superhit in the way of the title track of “Heroes”. Some of Lanois’ key contributions include a keen engineering-minded approach to the rhythm section, showing drummer Mullen the value of things like having multiple snares tuned differently, the use of different stickheads, and more nuanced and sophisticated approaches to building and developing a beat over time. Eno’s reputation and contributions to The Unforgettable Fire and everything that followed are of course not to be belittled either, but equal credit should be applied across the trio of figures rather than attributed largely to one.

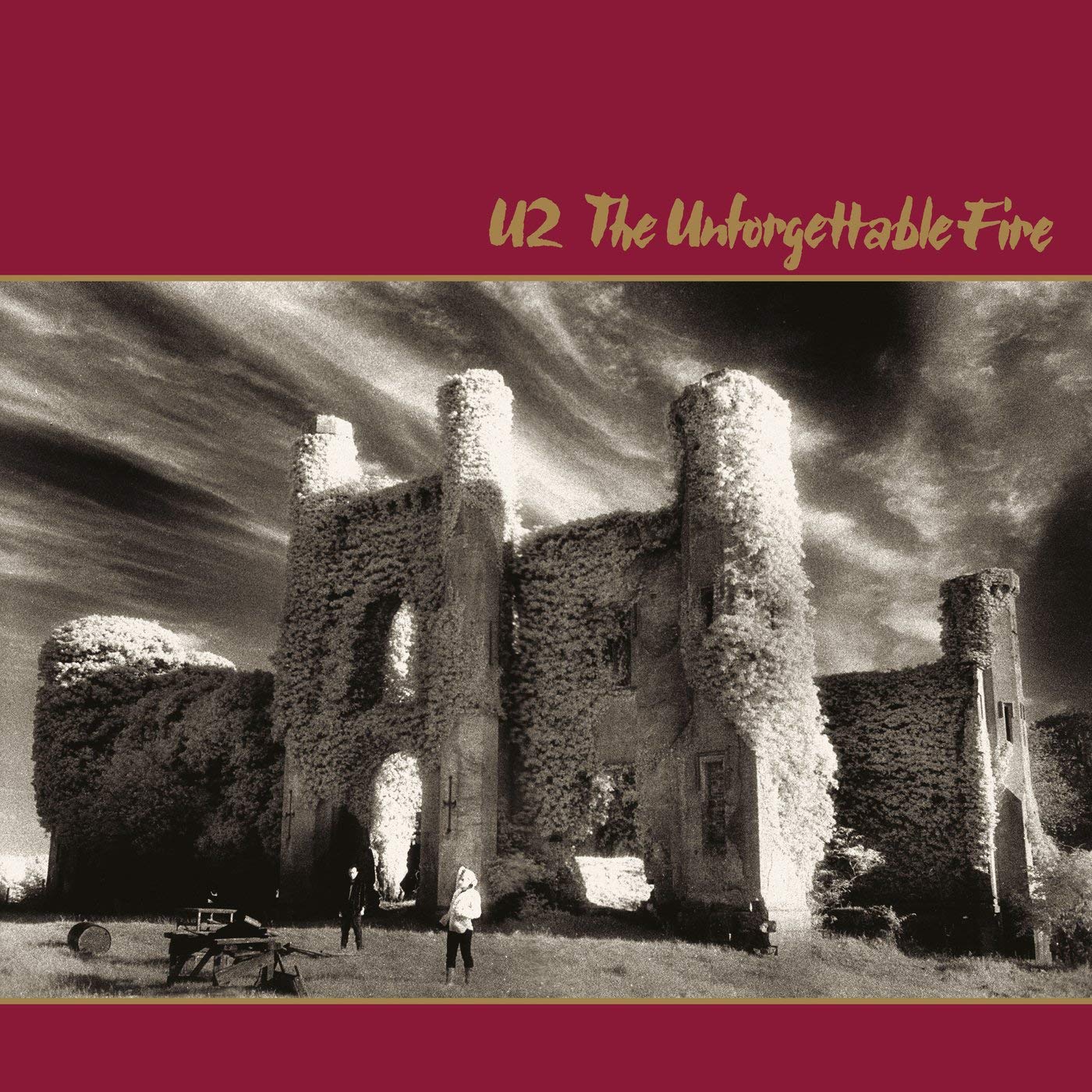

The interior image of the record is a curious one. The cover is of Moydrum Castle, an Irish castle the group was drawn to for its ambiguous shape and sidereal connection to the earthen mysteries of Irish mysticism. The title is plucked from a travelling exhibit chronicling the horrors of the unnecessary, cruel and violent nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. The record itself featured a number of songs inspired by figures of American myth, from the (relatively) recently deceased Martin Luther King, Jr. to Elvis to native Americans of the heartland. This leaves the record, like its lyrics and its swirling and hazy arthouse sound, a shimmering and clashing cascade of myth images plucked from all over the world. Rather than resolving these images, drawing a clear throughline for us, U2 instead swirl amicably about in the amnion, traveling from image to image the way mystics pace through the Tarot. What matters here is less the obvious and more the subtle resonance, with the beauty of Ireland stained by the Troubles and the famines inflicted by the British finding space with the complexities of an increasingly fascist Japan struck down by an equally imperial and nuclear empowered United States wishing to make a play on the world stage, itself conflicted by its own violence against native and black bodies both historically and in the present. Underpinning these struggles is always a sense of nobility and mythic beauty, something not quite like grandeur but instead closer to serenity or joy. The record then acts as a map of the liminal state between these forms, violence and beauty as equidistant thunderheads and monuments on the horizon.

There is a sense of travel captured in the album, leading us from their past to their future in a quite literal way. “A Sort of Homecoming,” in conjunction with the Irish castle of the cover, seem to gesture back to Ireland, the site of songs like “Sunday Bloody Sunday” from their previous record, War. “Pride (In the Name of Love)” acts then as a call to the myth-image of the group, a great and noble figure of recent history as proud and worthy of praise as any great figure of history calling to them from beyond the sea, an image worthy of following and exploring. The passage between invokes Hiroshima and Tokyo within “The Unforgettable Fire” as well as the scourge of drugs within “Wire” and “Bad”, passing through the shimmering aperture of atmospheric side-closer “Promenade” and ambient American opener “4th of July”. We arrive then at the clearing of the smoke of heroin within the mythic heartland of America, the home of its mythology, in “Indian Summer Sky” and “Elvis Presley and America”. The album then closes with its brief hymn to Martin Luthor King, Jr, the psychopomp of this spiritual journey, in “MLK”. It is there in the American deserts of its heartlands that the group’s next two records The Joshua Tree and Rattle and Hum would be centered, guiding initiates still unsure of what they were looking for, knowing only where they were guided to go to find it.

***

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

Langdon got me to care about U2. What a badass. Well written as always, Langdon. Your range, it is impeccable.

Hell yeah! Don’t forget to read the rest of the series (so far):

https://www.treblezine.com/category/feature/u2-101/