U2 101: How Boy and Three revealed an early and vivid portrait of the band

U2 is one of the most fascinating objects in the world of musical criticism and consensus. They are in turns wildly loved and wildly reviled, seeming in one moment to be the bridge from the world of pop to the world of the avant-garde while in the next revealed to be corruptive sell-out goblins. There is admittedly a great deal of this sentiment wrapped up not just in their music but in shall we say extracurriculars, be it the open activism of the group which has evolved over the years in ways not always pleasant or good, the revelation that the group’s LLC acts, as many large artists’ do, with cavalier and amoral movement of capital investing in anything that will raise the overall value of the brand (not to mention moving their legal position to Amsterdam to avoid taxation), to the eyerolling cliche of uploading one of their most recent albums to every single iPhone on the planet simultaneously. It would be baldly unwise and untrue to say that these actions have no value whatsoever in ascertaining the group but likewise it would be just as baldly reductive to turn a group that has been putting out records for 40 years over numerous different shapes and approaches into merely their publicly facing image.

Much like the shape of their activism, which has persisted over the course of their entire career, U2’s shape as a creative outfit has evolved and shifted over the span of the past several decades. What’s more, the group has rather miraculously remained the some foursome for their entire span, from their 1979 debut EP to the present day, something very few bands of any size do, let alone critically and commercially massive long-lived ones like this do. This solidity of identity on one front allows us to more concretely and directly engage with the shocking and fascinating shifting identity on the end of their work; no record’s shift can be attributed to a lineup change but instead solely to the shifting interests and directions of the players and their choices of collaborators, a process which accreted over time into the fascinating evolutionary genealogy of U2. In the interest of cutting closer to the core of the group, putting aside briefly their social image to focus purely on the overall body of their work, we present this project to you: an ongoing series evaluating the works of U2, album by album chronologically, both as independent objects and also as installments of the overall career-spanning project which is U2 itself, such that we might have a better understanding of a group at once so massively popular and strangely incompletely understood.

The group’s European grounding in punk is readily apparent on their debut and so far sole EP of studio material Three. The origins of the group came from the motley covers they played (or at least attempted to play), spanning from the Rolling Stones to the Beach Boys to the Sex Pistols to the Clash. These groups describe the overall shape, especially production wise, of the three songs contained in the EP, featuring a dry and stripped-down rock sound with charisma-driven amateurish vocals. It is perhaps shocking to those more familiar with the classic U2 sound just how spare and dry this is compared to the reverb-soaked arena-filling enormity of their typical sound. There was a deliberate choice with these songs to develop a sense of sonic toughness, centering the guitars and a much greater rock ‘n’ roll vibe than the band would later develop. Likewise the tenderness and sensitivity that typically marks the band is nearly entirely lacking here, with the group often instead having the rambling drive of a group like the Buzzcocks rather than the highly-coifed romantic heroes that would later inspire them. It’s a short release and the sole EP of studio material the group has released in their 40-plus year history as a group, but it offers a radical juxtaposition to their common image of their sound and approach as well as a necessary historical touchpoint for types of rock writing that would be the blueprint for each successive reboot of the band’s sonic identity.

Less than a month before the recording of the group’s debut EP came the release of then-obscure post-punk group Joy Division’s own debut Unknown Pleasures. This was too short of a period for its release to have great impact on the writing or recording of U2’s material but, in the year between the release of Three and Boy, the influence of Joy Division much more strongly asserted itself. This is most keenly felt in the rerecording of “Out of Control” and “Stories for Boys,” two of the three tracks featured on Three which here are instead given a stark and reverb-drenched post-punk veneer. The newer versions wind up feeling trapped somewhere between the claustrophobic and nihilistic void-vortex of early work from The Cure (who notably hadn’t gotten to these sounds themselves yet) and the snarled darkness of Joy Division themselves. Both Three and Boy were drawn from the catalog of songs the band had written up to that point, numbering over a hundred by the band’s own count, but the juxtaposition of the recordings of tracks featured on both reveals a greater level of assertion of the fundamental tenets of post-punk over the band’s songwriting, bringing them into a darker and more romantic direction than their earthy punkish strut had before.

The other key shift between their debut EP and debut LP was the selection of Steve Lillywhite as producer. While much has rightly been made of the group’s relationship with Brian Eno (though Daniel Lanois deserves equal credit), Lillywhite seems to only appear as a footnote to the overall picture of U2’s career to most people. Lillywhite pushed a great sense of fibrousness from the bass, giving that iconic post-punk rounded twang which enabled the bass to stand as the primary grounding figure for a number of tracks. This was necessary because already the Edge was moving into ambient guitar territory, an approach widely attributed to their collaboration with Eno but which clearly has roots back to this, their debut. Songs like “Into the Heart” are functionally kept pinned to the earth by the bass alone while the guitar does figure work and broad spacious color not unlike what later shoegaze bands would do, ringing out in reverb and sway against the dome of the sky.

That the song comes structurally as a the back half of a functional nine-minute song “An Cat Dubh/Into the Heart,” a sequencing often index as a single track in early CD editions of the album, also indicates a compositional ambition not often associated with U2’s early days, if it’s associated with the band at all. The first half of that longform piece is a stark and gothic array of blacks, drawing concretely from the anguished bleak concrete gray of Joy Division but set against a ravaged Ireland. There is something cutting about the way Bono sings out the sole chorus line, “I know the truth about you,” breaking into falsetto like a child’s taunt. It’s a song that drips with the romanticism of childhood, a romanticism that can breed witchlike shadows and leering darknesses just as it can produce colored fields and joyful singing. Both “A Black Cat” (its English title, often used in concerts) and “Into the Heart” focus on a foreboding sense of atmospherics in the guitar work, lingering like smoke on the air, the diminishing plumes of the former developing into the clouds of the latter. It indicates a group that had already moved past ideas of guitar-driven rock music being ramshackle glory, seeing instead a more romanticist sense of space that would later get attributed to groups like Cocteau Twins and This Mortal Coil.

These early works of U2 show a lyrical fixation on faith and man in its infancy. The songs on both Three and Boy, having been chosen from several available written by the band, form a curious cross-section of the early lyrical loci of Bono’s thought process. There is little in the way of a total map organizing the timeline of when these songs were written and what unrecorded material lay between them, rendering these particular works a rather opaque and hazy cloud when it comes to grasping those initiating thoughts that we might see developed over the span of a career. Three figures come out rather clearly, however. First is the clear wound of the loss of Bono’s mother, one that seemed to push him toward a dark and brooding introspection. These early pieces are more abstract in their relation to that loss than his writing would become over the years, here more a figmentary ghost coloring the patina of the material rather than a clear central figure. Still, given his development on lyrical snatches found here into more explicit explorations of that grief later on, as well as his own word on the matter, we can see that lingering loss intermingling with the reverb-drenched and rounded post-punk twang of the record. Second is the matter of God. The members of U2 are all Christians of varying levels of devoutness, understandable given their Irishness. Like the issue of Bono’s lingering grief, faith here is less concretely explored as it would become on later records and more an avenue toward a macroscopic scale and sense of poetry, gesturing to the universal and the abstract formal nature of things rather than their firm and fixed materiality. Their approach to faith leads U2 naturally to a kind of broad-hearted romanticism just as often as soul-bared spirituality; here it is more the former, but it is likewise the seeds for the latter that would come to show itself just one album later.

The final lyrical thread is the dominant one of this record, at least visibly, that being the firm and fixed materiality of youth and the experience of life. Bono may have crafted himself a parodic and overblown image in modernity and even a few years from the release of this record would find himself struggling to cross the gap between the mythic performer image and the reality of being a man in history and the world, but here he is thankfully spared of those things. The primary shape of these songs by and large are the ruminations of youth and life. It is on this bedrock of real human experience that the notions of the loss of his mother as well as thoughts of God and faith get cast like shadows or explicating rays of light, cross-examining the reality of his daily life as a man in all its smallness and firmness with those hazy macroscopic thoughts which nonetheless pierce the flesh of the world of the living. This provides a strong basis for the more romantic and abstract ruminations captured on this record, eschewing the image of U2 as purple-penned and overly-earnest by slicing clean with direct images of the life of youth.

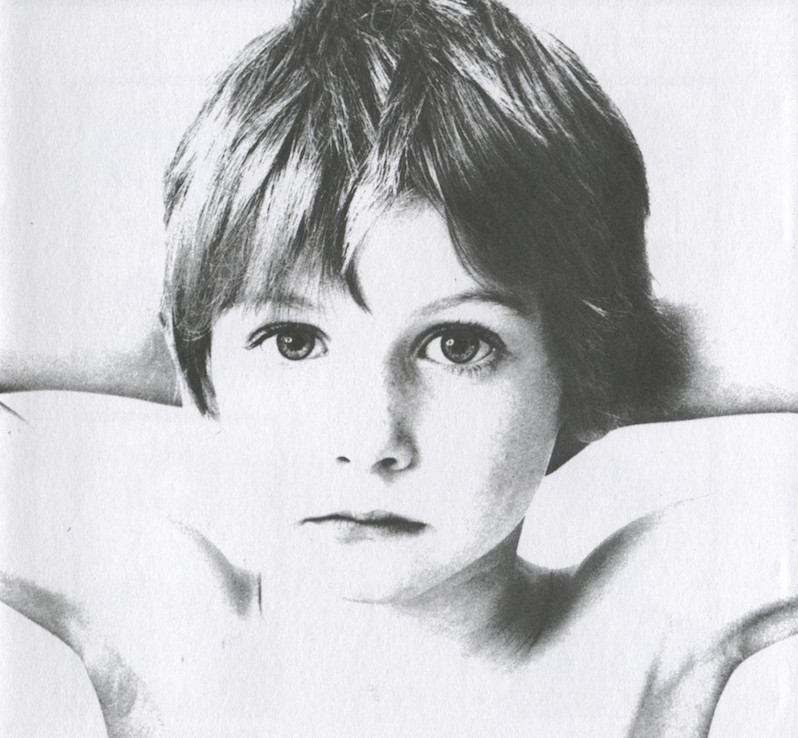

This is perhaps the most punk element of the record; here, before their mythic fixations would develop into the U2 that became one of the biggest bands in the world, they were still grappling with the question of how to marry those overwhelming yet seemingly invisible concerns with a material life that seems perpetually agnostic to our grief and spiritual longing. This connective tissue of youth and our gradually fading innocence as the mysteries of pain and joy in the flesh of history against the backdrop of God would become the defining characteristic of this early trilogy of recordings, depicted with curious masterfulness by the cover images. It is in fact the same boy on the cover of both Three and Boy, who would again later be used as the cover model for War, the final record of this arc. Between them, the cover of October was a picture of the band themselves, offering a thematic link between the two; the boy is them in the abstract, youths growing harder and fiercer, while they are the real humans behind.

The angularity and funkiness of “Twilight” is another great shock of their debut. The disintegration deconstructionist funk of Gang of Four feels especially present on that track, beginning in sonic terrain that groups such as Interpol would later explore before breaking into a bright major key chorus that arrives like a structural Picardy third, a strange and discomforting consonant close to an otherwise glowering and effulgent gothic darkness. “The Ocean” is a brief atmospheric piece, just over a minute long, built from ringing bass chords and guitar like single drops of rain. It seems immediately like a compositional precursor to the later experimental pieces the group would begin more fully exploring on The Unforgettable Fire forward. Most strangely, the group seemed to entirely drop these approaches in the studio until that point, making Boy a curious formal precursor to their more ambitious art rock material while more immediately being a prefigure to a tightened approach to songwriting and recording that over the next two records would increasingly sharpen their melodic sensibilities as well as their charismatic ability to command arena-sized audiences. “A Day Without Me” feels more in common with those two records to follow, being a fairly typical driving New Wave song, taking a slightly swung figure as the rhythmic basis and appending a very ’80s sixteenth note figure against it, similar to Stevie Nicks’ “Edge of Seventeen” guitar part. It’s strange hearing that piece near the end of Boy; it at once feels deeply out of place with the rest of the more experimental and gothic material present while also more obviously prefiguring some of the ideas that were to come.

The final tracks of the record play out in much the same way. The story of Boy from one end of chronology is one of promise and potentiality; from the other, it is an intense challenge, failing to hew to any of the common images of the group that many hold. These songs are not arena-fillers, instead hewing closer to the arthouse goth rock emerging from the post-punk movement at the time while occasionally breaking into more explicitly driving and straight ahead rock numbers. There is as much gauzy and experimentalist guitar playing as there is cliched strum patterns. The fact that these songs were all driven from a period of intense youthful productivity from the group, being a selection of 12 from among over a hundred, gives a sense of the scope of vision of the group as well as their still-undecided identity. Boy becomes structurally as much the beginning of a trilogy that would extend onto their next two records as it is the first record of a trilogy only continued on The Unforgettable Fire, rendering it the apex of two diverging images of the band’s trajectory. The rest of the band’s lifespan would be spent seemingly attempting to wrestle those two diverging paths of interest with one another, one wanting to be a large-than-life rock band inspired by the greatest rock bands of all time and the other an arthouse experimentalist outfit. That in turn makes Boy the ideal starting place for our macro-scale thesis told over the course of analyzing these albums; our interpretations of the group’s body of work, social image aside, tends to only ever be one or the other of these two figures, rarely both at once and almost never the complex dialectical interplay and relation between the two. But on Boy we get an early and vivid portrait of exactly that: the very center of U2, from then until now.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.