Da Art of Storytellin’: Why should we still care about the Grammys?

This is the first column post-Grammys, where many people heard the record scratch and collectively thought, “there is no way Adele’s album is better than Lemonade.” Even Adele herself was aware of the Grammys’ snafu, apologetically accepting the award while praising Beyonce. For fans of rap and R&B, this latest slight was no surprise. Aside from a handful of big names (Bey, Jay Z, Chance the Rapper, Tribe and Rihanna), most of rap and R&B’s biggest stars declined to attend the ceremony. One of the most notable no shows, Frank Ocean, granted a rare interview with the New York Times and explained his decision to not only not attend but not submit Blonde and Endless for award consideration: “That institution certainly has nostalgic importance. It just doesn’t seem to be representing very well for people who come from where I come from, and hold down what I hold down.”

For a lot of people the Grammys are a colossal waste of time. A ceremony where record industry insiders pat each other on the back and congratulate each other for this or that platinum-selling album. I distinctly remember in 1998 Radiohead’s OK Computer, arguably one of the most landmark albums of the ‘90s, losing Album of the Year to Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind—not a bad album, but how often does it really come up compared to OK Computer? Or come up at all? By and large reflecting the suits of the record industry, the nominating body of the Grammy Awards had (have) the reputation of being white, male and old.

Like the Academy Awards’ #Oscarssowhite debacle last year, Beyonce’s loss became symbolic for the larger issue of inequity within the entertainment industry. The last person of color to win album of the year was in 2008 with Herbie Hancock’s tribute to Joni Mitchell. The last hip-hop record to win album of the year (one of only two, to be clear), was in 2004 with Outkast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. For many who paid attention to this year’s ceremony, it was noteworthy that many of the awards given to Black artists fell under the categories of R&B, Rap or “Urban Contemporary” (IDK what that means), in other words, genres coded as “Black music,” but aside from Chance the Rapper’s Best New Artist win, the major awards went to white artists—namely Adele, who, one could argue, makes music that has its roots in Black music but has been made palatable for white audiences.

Why should we care? Adele’s 25 isn’t bad, and one could claim that there was no way the record industry would reward an album like Lemonade that so brazenly flaunted the traditional means of releasing music. Yet it became clear that it wasn’t necessarily just about Lemonade losing, but about the fact that industries—whether it’s music or film, literature or visual art—have consistently had a blind spot for diversity because they’re largely run by white men. For the music industry it’s prizing “authenticity,” when what that really means is a dude (or sometimes a woman) singing and/or with a guitar, and not a producer creating sounds from a synthesizer or samples. Having a single singer/songwriter somehow makes it better than something created more collaboratively. This narrow definition ignores other forms of making music, (not) coincidentally ignoring the cultural zeitgeist largely defined and shaped by hip-hop and more specifically by people of color. Think of the slang we use, the memes. Culture that is appropriated by not just white people, but by others as well. So much of it found root in Black communities, spread through social media until your aunt uses “fleek” in a sentence and you quickly drop it from your vocabulary (or a more horrifying scenario). But why then do people of color consistently have to fight for recognition? Why must a simply OK (at best) or mediocre album by a white artist get the big prize when an album by a Black woman that set off a cultural firestorm the minute it was released and, you know, was really really good, lose? It is easy to extend these questions to the whitewashing of roles in film and TV. To the kinds of books that get the big advances. To which artists get the big museum retrospectives. And it becomes a question of why we’re so willing to reward white mediocrity while asking artists and makers of color to work twice as hard.

The best hip-hop albums and mixtapes of the month

Migos – Culture

Migos – Culture

When Donald Glover stood at the mic at the Golden Globes after winning for best comedy for Atlanta, and thanked Migos—specifically shouting out “Bad and Boujee”—it was a surreal moment of realizing that thousands of people were quickly Googling “Migos” and “Bad and Boujee.” As a longtime champion of the Atlanta group, it was amazing to see how quickly that shout-out launched Migos into this other realm. They appeared on talk shows, “Bad and Boujee” was everywhere. For longtime fans, this win and recognition was hard fought. Their breakthrough Y.R.N. (Young Rich Niggas) came out in 2013 and since then they’ve released many mixtapes, collabs and singles, with a varying degree of quality but still uniquely Migos. Their first official album, Yung Rich Nation, bore the marks of first album anxiety and while not bad, felt stiff in comparison to their mixtapes. Their latest, Culture, on the other hand, shakes off the forced aspects of Yung Rich Nation, and delivers a release that is assured, leaning in on its narratives and emphasizing a unique kind of emotional journey. Singles aside, Culture’s highlights double down on Migos’ Migos-ness. “Big on Big” is defiant, outlining the group’s label troubles, and finds the group easily trading verses, playing off each other in that unique way that makes Migos so fun to listen to. Better still is the loose and loopy “Slippery” with Gucci Mane, a minimal woozy synth weaves in and out, complimented by a subtle Trap beat, letting the trio and Mane enough room to play. That Culture is such a strong showing is a boon for Migos at this moment, when so many eyes are on them. Culture is a welcome showcase of what longtime fans have loved about the trio, while allowing them to flex muscles they haven’t gotten to before.

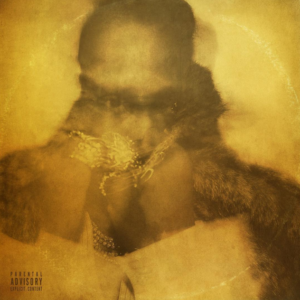

Future – FUTURE

Future – FUTURE

Future’s latest release came out just a few days from when I’m writing these words. So forgive me if this review is a little short—I just haven’t spent a lot of time with it. But….it’s quite good. And I fully own up to my soft spot for Future; I’ll find the time to listen to his mixtapes even if I think they are subpar. If there’s a fault to this eponymous record, it’s that it doesn’t exactly break new ground—we’re still exploring the dark underbelly of Future’s life, money, women and drugs etc. But it is endlessly listenable. Songs like “Zoom” and “Super Trapper” were instant repeat plays, with Future nimble and energized. Do I love this as much as I love 56 Nights or Beast Mode? Maybe, but it’s still too soon to tell. But do I enjoy listening to FUTURE? Hell yeah.

Latasha Alcindor – B (LA) K

Latasha Alcindor – B (LA) K

And now to break from the hyper (and sometimes toxic) masculinity that can plague hip-hop, we come to B (LA) K, an experimental and wildly different album by Brooklyn’s Latasha Alcindor. Using poetry, recordings of news reports and quotes from various voices, Alcindor weaves together a potent portrait of Brooklyn. B (LA) K touches on gentrification, racism in the form of both institutional and everyday microaggressions, the continued abuse of police power, and on and on. What’s lovely about B (LA) K is that through her incorporation of other voices, it never feels like a lecture or a monologue, but rather a portrait of a rich multitudes of experiences. Alcindor’s earthy voice is forceful and wily; she relishes in her verbal play and adds gravity when the subject calls for it. There are times where I feel incapable of really articulating and understanding what makes releases so important because my lived experience has been so different from the that of the artists that makes these records. With B (LA) K, I feel acutely aware of what I should speak on these subjects, and which are not mine to tell. Yet at the same time, my intuition and my empathy for these narratives and these forms of expression are what push me to say, ‘hey! this right here.’ So this right here. This album that might not speak to your lived experience, but is a profound work that deserves your time.