10 Albums with two distinct sides

This week we learned that vinyl pressing plants are having trouble keeping up with increasing demand. And that’s a bummer, but it’s also interesting to see how enthusiastic people are about vinyl these days. A lot of that has to do with the inherent disposability of CDs and the ephemeral nature of MP3s, but a lot of it has to do with having a particular experience with your music, and part of that experience comes with having two sides of an album.

Splitting an album in half is a practical matter with LPs, simply because you can really only fit so much music on one side. But that doesn’t mean you can’t get creative. In fact, some artists have used the otherwise utilitarian concept of sides to introduce an entirely new aspect to the music itself. For instance, Bob Dylan split his 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home into acoustic and electric sides, while The Beatles loaded the second half of Abbey Road with a lengthy suite of small, continuously changing pieces. And those are just two examples of how to make a side a work of art in itself. So, to highlight the wonders of the album side, we present 10 albums with two distinct sides — 10 of our favorites that is. Don’t forget to flip it over halfway through!

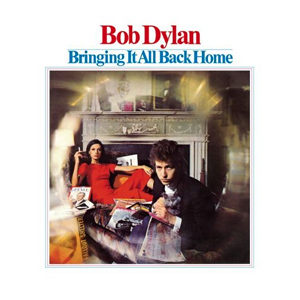

Bob Dylan – Bringing It All Back Home

Bob Dylan – Bringing It All Back Home

(1965; Columbia)

Forget Metallica and Neil Young in the ‘80s: The most Shakespearean example of a musician alienating his assumed fan base was Bob Dylan in 1965, when he cast off his hootenanny cred and went electric. This so aggravated community organizers that it harshly split his audience at the Newport Folk Festival, unleashing (apocryphal) rumors that Pete Seeger sought an axe backstage to hack the power lines. Cooler heads prevailed, both on that day and in the larger scheme.

If they had listened to Dylan’s most recent album at the time they might have seen it coming. Bringing It All Back Home showed yet another side of Bob Dylan (sorry) with the fiery, electric Side One, and the self-accompanied, acoustic Side Two. But both sides signaled a dramatic break from the folk questioning of his first four albums. It’s where Dylan blew up the rule book on popular songwriting, practically inventing another language altogether. The siren call of “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” the heat-stricken ire of “Maggie’s Farm” and the brash comedy of “On The Road Again” and “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” jolted Side One, side-by-side with his most mature love songs to that point, “She Belongs To Me” and “Love Minus Zero (No Limit).”

But Side Two was more unsettling, even if the setting was quieter and more familiar. I don’t know if the broken-up soul in “Mr. Tambourine Man” ever did get off that block. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” almost casually deconstructed the implicit hope of his early folk associates in unsparing, wearied acquiescence, and it spread to the personal realm with the cruel-to-be-kind “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” While Side One brought the sonic shakeup, Side Two refused to console the faithful. That left only one option for Dylan and his audience: waking up, growing up, and finding entirely new ways to learn old truths. – PP

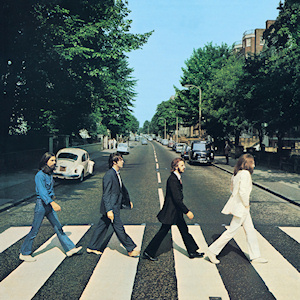

The Beatles – Abbey Road

The Beatles – Abbey Road

(1969; Apple)

I find it karmic that we take up this theme in the same temporal breath as our acknowledgement of the 25th birthday of Paul’s Boutique, because that album channels this Beatles release in more than one way. Both were born amid stewing turmoil: The Beastie Boys were rebelling against their friend Rick Rubin, against the Def Jam label, and against their East Coast roots. The Beatles, meanwhile, had many hands on many throats — Lennon vs. McCartney, producer vs. Lennon, McCartney vs. business manager, Harrison and Starr vs. Yoko Ono. In the front half of Paul’s Boutique we hear “The Sounds of Science” rest on a skillful arrangement of Beatles samples, one of the few times the Fab Four have ever received this turntablist treatment. On a larger scale, the front of Abbey Road was essentially John Lennon’s baby, a set of self-contained blues, balladry, and fantasy organized to once again show off the band’s skill. In the back half of the Beasties’ album we hear “B-Boy Bouillabaisse,” a pastiche of partial ideas and rap sketches from reluctant, possibly blissfully unaware musical savants. The back half of Abbey Road was handed off to Paul McCartney and producer George Martin, anchored by a medley of small compositions piecing together small compositions as a throwback to the heady, artsy days of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Upon release? Yeah, fans and critics of each band kinda went, “Something is wrong with you people.” As time has passed? The respective albums are arguably each group’s most beloved. Does this mean that The Beatles were The Beastie Boys of their day, or the other way around? – AB

Neu! – Neu! 75

Neu! – Neu! 75

(1975; United Artists)

With Neu! ’75, it was clear that both Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger had something to say. The ambient and serene first half represents what Rother’s distinct interpretation of the German krautrock explosion was, while the ballsy proto-punk-ridden second side demonstrated Dinger’s ability to uphold the “rock” in krautrock, while keeping it a bit more straightforward and edgy than the usual flavor. It’s difficult to find an album that executes two different styles in the way that this one does. With “Isi,” it’s hard not to be swept up to the clouds by the angelic motorik drum beat and heavenly keyboard overtones. By the time the minimal blissfulness of the first side has come to a close, “Hero” does well to transition over the record to its final three attitude fueled punk blueprints. It’s easy to see why music titans like David Bowie and Brian Eno took notice of this one; everyone else should do the same. – GS

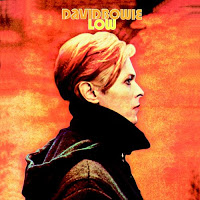

David Bowie – Low

David Bowie – Low

(1977; RCA)

Ten years ago, Pitchfork named Low as the number-one album of the 1970s. Without doubt, the 70s were a stacked decade for recordings that are now regarded as classics — Unknown Pleasures, Entertainment!, Led Zeppelin’s IV, Blood on the Tracks, Marquee Moon and London Calling were all behind Low in the top 10 of that aforementioned list — but David Bowie’s masterpiece was more bizarre and experimental than any of them. Low was already Bowie’s ninth album of the 70s (Heroes and Lodger would make 11!) and the seven rock-oriented, short, and weird songs of side A gave way to four longer, more ambient and spacious tracks on side B. The two sides of Low could be heard as polar opposites; the instrumentals of side B were originally planned to soundtrack Nicholas Roeg’s 1975 film, The Man Who Fell to Earth, which starred Bowie, but the four suites were snubbed. Taken into context for its 1977 release, Low is the apex of rock’s experimentation with electronics. Brian Eno’s influence can be heard; next to Bowie, he’s a main player, but it was Tony Visconti who helped produce the album. Bowie and Eno give the songs numerous textures and treatments with saxophones, xylophones, vibraphones, harmonica, pianos, synthesizers, Minimoog, and an electro-mechanical keyboard instrument called the Chamberlin. But side A of Low wouldn’t be what it is without Carlos Alomar’s snarly, enlightening guitar work. Alomar practically disappears on side B as the record becomes a soundtrack for a float to the moon. Abstract, shimmering, and able to force deep thought, Low became the future. – JJM

Kraftwerk – Trans-Europe Express

Kraftwerk – Trans-Europe Express

(1977; Kling Klang)

There are technically eight tracks on Kraftwerk’s Trans-Europe Express, the Düsseldorf-based electronic pioneers’ ambitious follow-up to Radio-Activity. But it’s more accurate to look the album as featuring three pop songs and one extended suite; like Abbey Road before it, Trans-Europe Express dedicates its entire second half to a sprawling set of interconnected pieces. But I’m getting ahead of myself — Trans-Europe Express, on the whole, is made up of fascinating conceptual arcs about perception and reality, as depicted in the ominous electro-dirge “Hall of Mirrors” and the more upbeat “Showroom Dummies,” each of which deals with ideas of how we see ourselves, or how we see others. But there’s also an underlying idea about identity on a more specific scale, particularly the band’s connection to Europe. Here, the band makes a statement about being European rather than simply being German, and it’s here where the second act comes in. On side two, Kraftwerk boards the title railway and heads out on an epic, four-piece excursion that pays tribute to the European rail system of the same name, while charting a highly danceable groove. Though pretty much every Kraftwerk album is high concept to a degree, this one is perhaps the most poetic, if not the most immediate. That doesn’t mean it’s not the best. – JT

Neil Young & Crazy Horse – Rust Never Sleeps

Neil Young & Crazy Horse – Rust Never Sleeps

(1979; Reprise)

By 1979, Neil Young already had a successful career under his belt, including work with Buffalo Springfield, a short-but-memorable tenure with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, a handful of well-received solo albums, and even a decade of recording with hard rock outfit Crazy Horse. Despite all that prior acclaim, critics and fans alike had begun to wane away from Young’s folk-leaning stylings. But it’s not like Young to give up when he’s down. Instead of laying down his cards, he dropped a Royal Flush in the form of Rust Never Sleeps. Both sides are mostly live recordings with minimal overdubs, with side A focusing on a more lyrically robust revisit to Young’s classic style. But side B saw the singer/songwriter reuniting with Crazy Horse to create a roots-rock hybrid that was pretty damn edgy for its time. To hear the contrast for yourself, you need only play the opening and closing versions of “My, My, Hey, Hey” back to back; both are equally engaging but one is calming and entrancing while the other is raw and beautifully intense. – ATB

Pink Floyd – The Final Cut

Pink Floyd – The Final Cut

(1983; EMI)

Depending on whether you’re a Waters fan or a Gilmour Fan, The Final Cut is either one of the band’s best or worst albums. Since it includes a few outtakes from The Wall, themes of war and its impact on survivors (participants and loved ones alike) can be found in several songs of what some cynics consider to be Waters’ first solo album. Waters’ vision of The Final Cut included dividing the songs into two acts. Side One was sung from the point of view of a damaged hero returning home from the war, and it described every facet. The Final Cut starts with our hero lamenting the failure of the “post-war dream” – a world repaired by countries’ fighting. He struggles with how the public reacted to his return (“When we came back from the war / the banners and flags hung on everyone’s door”) versus what he knew the reality was – children being led to slaughter.

He is haunted by a memory “that is too painful to withstand the light of day,” of “the gunner’s dying words on the intercom.” Finally, he knows he must try to hide it all away “behind paranoid eyes.” But in reality, he knows, as we all know, that war is never over. Side Two makes this clear. The songs follow a path, beginning with a battle over claims to a desert to a peek into the mind of “tyrants and kings,” to a devoted woman as she “bravely waves the boys good-bye again.” It’s the “again” that drives the point home. Finally, with “Two Suns in the Sunset,” we all perish, victims of a nuclear attack. As we turn to charcoal, Waters’ final words as a member of Pink Floyd say it all: “Ashes and diamonds, foe and friend, we were all equal in the end.” The Final Cut, like it or not, contains some of Waters’ most visceral lyrics, and we can learn something from both sides of this tale. – CG

Kate Bush – Hounds of Love

Kate Bush – Hounds of Love

(1985; EMI)

Kate Bush has always been a pretty high concept artist, and on her greatest musical achievement, 1985’s Hounds of Love, she wrapped up concepts within concepts and packaged two different suites on opposing sides of the album — sort of. The first half, simply titled “Hounds of Love,” is the one with the singles: “Running Up That Hill,” “Hounds of Love” and “Cloudbusting,” each of which is a booming masterpiece of production and songcraft. And its other two tracks, “The Big Sky” and “Mother Stands for Comfort,” at least fit in sonically, marrying Bush’s penchant for booming production and intricate beauty. The second half, “The Ninth Wave,” is the weirder and artier of the two, following a narrator who is lost at sea. Though it’s also a bit more metaphorical in a sense; it’s more about the narrator’s personal struggle with faith and meaning, which actually gets pretty damn intense when you get to “Waking the Witch,” what with its demonic courtroom scene. Yikes! But it’s also the more complex of the two halves, which doesn’t make for great singles, but does make for a truly amazing whole. The thing about Hounds of Love, however, is that—like every album here, come to think of it—even with two separate and distinctive halves, it’s the complete package that’s the most impressive. – JT

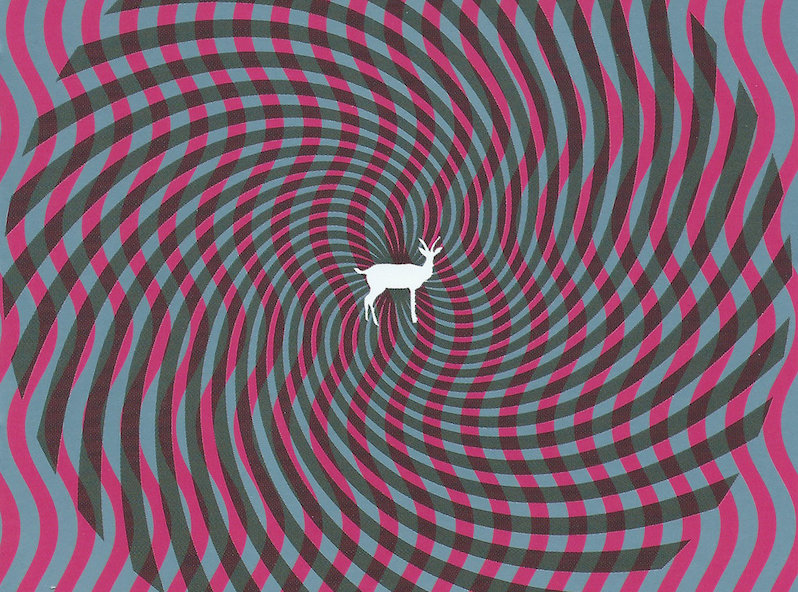

Deerhunter – Cryptograms

Deerhunter – Cryptograms

(2007; Kranky)

Deerhunter’s aggressive dance punk on Turn It Up, Faggot was good; Cryptograms was incredible. After sessions in New York City failed to produce an adequate follow up, the band returned to Atlanta, ready to call the project a failure. Thankfully, the ever-experimental Liars convinced them to give it another go. The resulting LP was recorded in two separate, day-long sessions, set months apart. The first half is mostly instrumental — a lush, ambient series of shoegaze and psychedelic compositions with occasional, heavily filtered vocals. But beginning with “Spring Hall Convert,” side two transitions into a series of dreamy, warped pop songs. Together, the two halves create an eclectic journey, like coming out of an interrupted dream and into a sleep-deprived stupor. Despite initial difficulty, Deerhunter managed to form the two distinct sides of Cryptograms into a single engaging masterpiece. – ATB

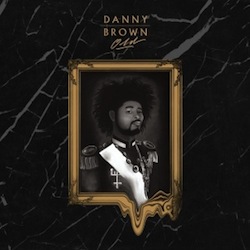

Danny Brown – Old

Danny Brown – Old

(2013; Fool’s Gold; 2013)

Detroit emcee Danny Brown makes the distinction clear on the opening track of Old’s side B: “This the last time I’m a tell you, wanna hear it? (Here it goes!)” While side A deals with trap themes and Brown’s drug dealing past, “Side B [Dope Song]” is clear mission statement — his last dope song before unleashing nine consecutive EDM-infused bangers. Each side would be a perfect (if short) album in its own right; the rhymes, themes and production are solid throughout. But, by combining the two, Brown was able to have his cake and eat it too; Old contains just as much socially conscious street credit as it does club-worthy playability. By successfully playing up both sides of his personality, Brown turned out one of the most distinct and focused hip hop albums to drop in the recent past. – ATB

I’ve never heard of any “Danny Brown” or “Deerhunter” – and that’s “favorites”? In the US of A maybe…

.

.

What’s the difference between USA and Joghurt?

.

Joghurt has culture.

Well… they are American artists. Listening to music from the U.S. won’t hurt you. We promise.