Alice Coltrane’s Journey In Satchidananda is a collision of grief and self-discovery

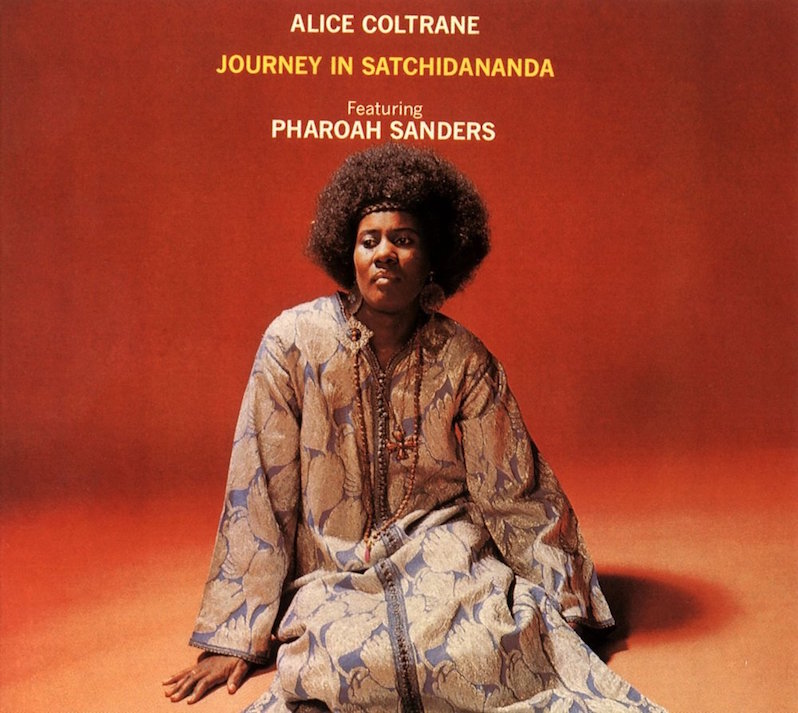

Alice Coltrane’s imaginative musical landscapes sound like no other. Her music has influenced a diverse list of artists ranging from Kamasi Washington and Flying Lotus, who is actually her grandnephew, to Sunn O))), who named a song after the jazz legend on their 2009 album Monoliths and Dimensions. And though she received unfair criticism early on in her career as the Yoko to John Coltrane’s “Classic Quartet,” Coltrane is now remembered not only as a crucial contributor to her very famous husband’s most revolutionary musical period, but also as a visionary artist in her own right. Dedicated to spirituality as much as to music, the musician, composer and swamini left behind a rich legacy that continues to enchant and captivate 50 years on from the release of her best-known masterpiece, Journey in Satchidananda.

Born in Detroit in 1937, the classically-trained pianist Alice McLeod’s earliest musical experiences were in her local church. Discovering bebop as a teenager, she later moved to Paris, where she studied jazz with Bud Powell. After a failed first marriage, she returned to her hometown and soon became an in-demand improviser. It was her work with vibraphonist-bandleader Terry Gibbs that brought her to New York, where she first met John Coltrane. Alice and John quickly became romantic, musical, and spiritual partners, sharing a strong interest in Indian religion and philosophy. Together they had three children, and in 1966 she replaced McCoy Tyner as the primary pianist in her husband’s band.

In 1967, John Coltrane died after a brief battle with liver cancer, which he kept hidden from most of his friends and peers. The sudden death of her husband left Alice devastated. In the depths of her grief, she turned inward, developing a deeper connection with Hindu spirituality. Her healing experiences with this faith as well as its music became a strong influence on her work as a bandleader and composer. Journey in Satchidananda, her fifth album, was named for Swami Satchidananda, the guru and yogi who famously delivered an opening prayer at Woodstock. Coltrane met and became his disciple in 1970, and she recorded the album later that year.

Equally important to her musical evolution during this period was the harp, an instrument that John had purchased toward the end of his life that did not arrive at the family home until after his death. Coltrane taught herself the instrument, developing a distinctive rippling style that was an apt musical expression of the transcendence she sought. “I once remember lying in my bed waiting to go to school, and I woke up to this beautiful harp music just filling the house,” her daughter Sita Michelle Coltrane remembered. “And I thought ‘Wow, if heaven is like this, then I’ll be certainly ready to welcome it when I get my chance.’”

Journey in Satchidananda feels like a culmination of sorts: a collision of loss with newfound understanding and self-expression. The music occupies the liminal spaces between East and West, post-bop and raga, grief and healing, consciousness and transcendence.

The opening title track emerges from a memorable bassline by Cecil McBee. Backed by tambourine and a droning Indian string instrument called the tanpura, the arching line takes on a mystical quality. The music’s trance-like nature is elevated when Coltrane’s harp bubbles to the forefront, filling the musical space with waves that expand in all directions. A commanding soprano saxophone solo by Pharaoh Sanders mimics the motions of Coltrane’s harp. While melodies occasionally emerge, the wash of sound created by Coltrane’s orchestration is the primary focus. The layering of drones, harp figurations, and the ever-present bassline has a soothingly hypnotic effect.

The following track, “Shiva-Loka” (or “Realm of Shiva”), is named for one of the members of the Hindu trinity, the “dissolver of creation.” It begins with effervescent ripples of harp, percussion, and bowed bass, and transitions seamlessly into groovy interplay between bass and saxophone. Coltrane demonstrates the diversity of her new instrument, using it in more percussive ways alongside her signature billows while tanpura and percussion fill out the ecstatic atmosphere.

With Coltrane on piano instead of harp, the brief centerpiece “Stopover Bombay” builds on the momentum of the previous track, translating it into a more recognizable jazz tune colored by Sanders’ idiosyncratic playing. His swoops and scoops give way to “Something About John Coltrane,” a more contemplative composition built on fragmentary themes by Coltrane’s late husband. An intoxicating blend of bass, tanpura, and percussion forms the backdrop for Coltrane’s harmonically adventurous piano improvisations and Sanders’ colorful blows. At one point, they yield the floor to McBee for a frenetic solo; you can almost feel his hands dancing up and down the neck of his instrument.

Final track “Isis and Osiris” stands apart from the others for several reasons. Recorded live at the now-defunct Village Gate in New York, it features Charlie Haden on bass and Vishnu Wood on oud, a lute-like instrument typical in Middle Eastern music. It’s also by far the most abstract piece; six minutes of free improvisation amble by before a clear theme emerges. You can picture the hazy jazz club atmosphere and its effect on the players, completely unbound by the constraints of the studio and free to venture beyond musical consciousness. A burst of applause brings the journey to a close.

Journey in Satchidananda’s spiritual jazz was not without precedent. Coltrane had similar-minded contemporaries in the likes of Sanders, Don Cherry, and Sun Ra, among others. Listening to the albums that came out of this small yet influential movement side-by-side, one is struck by the overwhelming tranquility that permeates Journey in Satchidananda. While many of these artists utilized cacophony and maximalism to evoke the divine—something Coltrane would go on to experiment with herself on later albums—her approach on Journey in Satchidananda is more subtle. Drone, bass, and wandering melodies are woven together in a spiritual invocation that soothes rather than agitates, enveloping the listener in Coltrane’s unique vision of transcendence. More than anything, Journey in Satchidananda’s magnificent soundscapes carry a deep sense of healing, reflecting Coltrane’s own journey and subsequent transformation in the face of grief.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.