I’ve always struggled with masculinity. I’ve done my best to conform to its image, imperfect and haphazard: I have worn leather jackets and long greasy hair, gone to the gym and learned to shoot a gun, carried knives and picked meaningless fights with strangers. I’ve drunk whiskey and beer, fancy and cheap, and sat in staggering drunkenness at midnight tables pouring my heart out to other men in the barely silenced grief we all carry. These struggles have sometimes hurled me in the opposite direction: I have worn dresses and makeup, gone by different names, imagined myself with another body and half-heartedly googled transition processes. In the nascence of my rising feminism in my early twenties, I came like many did to loathe masculinity, to find in it nothing worth salvaging. The worst of the abuses of my brother and peers came in its shape: the homophobic slurs, the insistence that my failure to be a man meant I was a woman, the very worst thing, even worse than being gay, and how my resentment toward that impossible disfiguring code marked so much of the arc of my life, from the midnight flight to literature and film and music to the kinds of art I would create and the kind of philosophy I would indulge in. It was a cage and I a bird, flapping my wings and pecking at my feathers until bald, screeching and panicking behind the bars. But there was always Bruce Springsteen, a star pinned to the velvet of the sky.

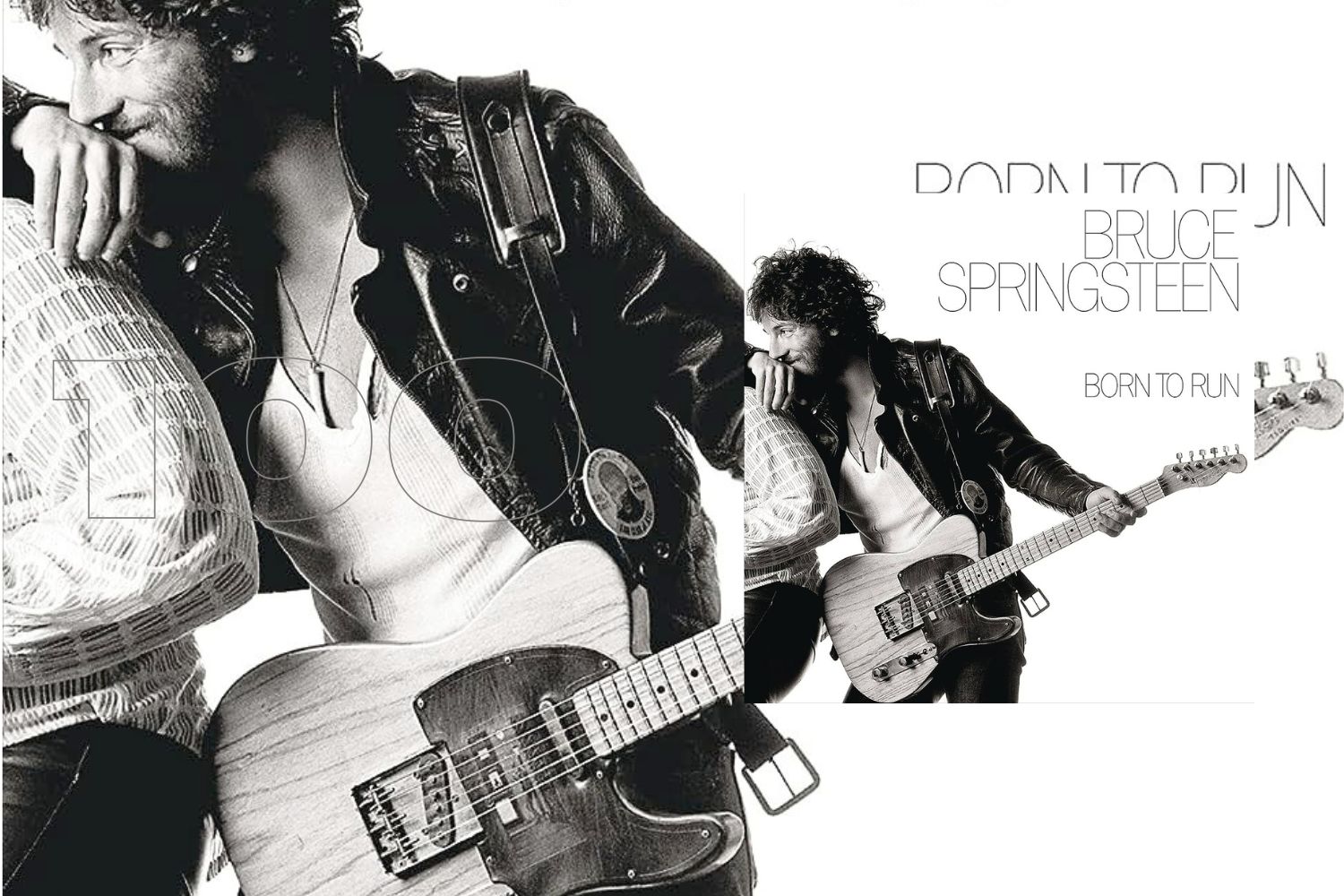

As an adult thankfully free from the bonds of binary gender, despite how others perceiving me would like to append it back onto me, I have a repaired relationship with masculinity these days: therapy and time will do that to you. (There is a pernicious violence against non-binary people of both assigned genders, where when performing suboptimally people will hurl gender back onto you to make sense of you, make you a man or woman not to celebrate but only to castigate and denigrate you.) At some point, the rubble and shrapnel buried in your heart has to be pried loose. I can thank Bruce for that too, at least in part. I look at the cover of Born to Run, that sacred document, the most important one he ever gave to me, the smile on his face as he leans on his dearly departed brother in Clarence Clemons, who he’d kiss on stage in love, an unfettered masculinity, and I feel a swimming in my heart. It is not just the music: it’s the lyrics, the poetry, the image. I am compelled toward this new image of a masculinity, not necessarily a manhood but something else, something beautiful and wounded and nurturing and healing and powerful and weak and everything. I am healed.

***

I was six years old and the mail had just come in. There was a long cardboard box, the type I’d learned to recognize by sight, my mouth growing wet with anticipation like a dog. We were members, as per the ritual of the era, of the Columbia House Record Club and its various clone programs and so it was not unusual for CDs and cassettes to come streaming into the house at irregular intervals. Sometimes, if my brother and I were lucky, we would be given the catalog and allowed a chance to peruse it and select an album or two to fill out the minimum for the penny album deals they used to have. Most often it was my father who made the selections. He had a record collection to replace, after all, having famously lost, per the familial myth, the vast majority of his LPs during his second divorce, when his soon-to-be ex-wife stole several crates plus his motorcycle. We always figured this was just a way for him to control the lion’s share of orders, but we never really minded. After all, his taste was the formative stone upon which ours was founded.

I was an impatient child. I secreted the cardboard box under my shirt when giving my dad the mail, dipping away to the sitting room, the place no one was ever supposed to go and where I frequently stole myself away to, in order to open it. There, in white, a man in black leather with his hands in his pockets and a telecaster strung to his back stood with his back to me. Bruce Springteen, Greatest Hits. I’d heard the name, the hushed worshipful whispers of my father and swooning eyes of my mother, but I couldn’t recall if I’d heard the music. I was six, after all, and while I was quickly developing a knack for remembering records, films and novels, my nascent autism finding its artful fixation, I hadn’t quite gotten it all under my fingers yet. There was one way to be sure, though. Away, to my boombox my father had gotten me, my tiny fingers peeling back the obnoxious layers of plaster and impossible sealing stickers keeping the case closed, all to get the CD in, volume low enough to keep it secret but loud enough for me to hear, my head pressed against the speaker, eyes closed, waiting. The first track was “Born to Run.” The second, “Thunder Road.” As the second song reached its end, I reached my hand over and pressed stop. I’d heard enough. I needed to go to the source.

I don’t know how long it took for me to finally hear Born to Run. It must have been years; the first time I can clearly recall having it in my possession was in middle school, when the days of my stealing records had evolved past stealing them from my family to stealing them from the mall. There were no other tracks from Born to Run on that hits comp, and try as I did, none of the others ever captured the same magic those first two did. Not that I didn’t learn to love The Boss overall through them; the songs reminded me of my father, the version of him at least that crawled back from the jungles of Vietnam to my grandparents’ home in South Carolina and, finding it inhospitable to his mind, got on his motorcycle and drove north to Boston, to New York City, trading jungles for jungles in search of some way to live. It was mythologizing, I knew. What I didn’t know at the time was how my father was fleeing his first marriage, forced by my grandmother’s hand despite the lack of faithfulness (if you can even call it that) of the woman while my dad was in that jungle war, how he sold drugs for a long period up north, his time as a studio musician. There was just a mythic masculinity, the way the world wants to kill you and the way you have to say no, to find dignity in your life as a rat and roach before it lets you be a man again.

“Thunder Road” was the key for me, however. I would listen to the song on repeat, skipping straight to track 2 and setting it to loop, laying there with my eyes closed and dreaming. To this day, it is still in my mind the greatest love song ever written. I’d been raised in the semi-rural south with family in far more rural areas. The imagery of the screen door, the fields of grass, the endless road and the desire to either leave or burn it all down all for want of love flickered even in my young heart. Yearning starts young, after all; you don’t always learn to hate your hometown as a kid, but you certainly learn to dream big even then, or at least I did. So imagine my delight when I finally pinched myself my own copy of the record and what was the first track but none other than this masterpiece of a song. It felt providential: I would have to put on this album and, like a novel, devour it.

This record became the turning point of Springsteen’s career, the center around which he still turns.

What came over those eight tracks felt to me like a desert flight, me and Muhammed on the backs of angels racing to our own personal Jerusalems. There is an arc to the record, each of its two sides preserved even in CD and digital formats by keen sequencing. The beginning is always an elegy, thunder roads and the youthful desire to fly free. Ironically, though side one opens with (to my ears) the greatest love song of all time and side two opens with the title track, a ferocious ode to night flights and long drives and the impossible optimism that if you journey far enough you will find for yourself a home, the middle two tracks of each side seem reversed, like they were children swapped at birth or strands of a braid crossed over. Side one continues with “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out” and “Night,” songs which do not remind me of the yearning of love so much as the yearning of home, searching desperately for a place to lay your head where you can one day be loved, if not today. Meanwhile, side two has “She’s The One” and “Meeting Across the River,” songs strongly associated with the healing aspect of love, that home is not a location but the act of loving itself wherever it is. Beatrice guides Virgil through Hell; one day, he realizes she herself is heaven, an angel in human form. But the final tracks of each side offer no resolution, only confusion, “Backstreets” and “Jungeland” completing the braid of these dual narrative threads of the desire for a woman and love and the desire for a home and peace and freedom. In each, our Virgil arrives questing for one only to find the other and, worse, that it has departed, that he is ever in the labyrinth of confusion; distraught, he cries out, literally in the case of the finale of “Jungleland,” and in those mourning cries is called to lift his head, get up onto his feet and journey again for the new form that has alchemically arose, alternating love and home, home and love, in an eternal quest. The end of Born to Run feeds back into the beginning. There is no completion, not for these desires. There is only eternal recurrence. An endlessness of desire, desire itself.

***

One of the most enthralling aspects of Born to Run is its function within Springsteen’s broader discography. I don’t mean to impugn those first two albums of his. Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ and The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle are both brilliant rock records, rightly lauded for their promise of a young songwriter and his excellent band. The E Street Band was an exciting project, managing to marry at the hip the rustic heart of rock and roll in its proletarian glory with the art house prog rock ambitions of psychedelic- and jazz-influenced groups. Their arrangements were delicate and complex but the melodies and rhythms direct, songs about life and the human shape of things rather than fantasy or abstract philosophy. They found in the center of those two poles tugging at the shape of rock in the early ’70s the figures of Roy Orbison and the Beach Boys, each emblematic of different ways of marrying the theatrical and prog-like levels of complexity into more direct song structures and approachable shapes. The E Street Band and Bruce as their leader, in short, were not anything but brimming with potential before Born to Run was dropped.

Despite that burning sense of ambition lighting up their belly, there is still something fantastical about how much better Born to Run is. I have rhapsodized about Ride the Lightning as the holiest of the holies, but it is largely indisputable that Metallica arrived completely with Master of Puppets; like that record, Born is Bruce’s third, the one where all the pieces come together and, like that most perfect of Metallica records, the title track here is perhaps the greatest encapsulation of the E Street Band and Bruce himself of any single song they’ve penned. In its four and a half minutes, we see eternity spool out, every arrangement trick in the book brought to bear. It has no chorus, instead seeming to draw on the Beach Boys’ “Surf’s Up,” making every 30 seconds burst open like it had all been an introduction leading to this, onward and onward until at last the rocket blasts fully apart. The difference between these two masterpieces, and likewise between it and that most perfect of Metallica tracks, is that “Born to Run” doesn’t even need a chorus when every single line is so often sung by listeners with the kind of fervor and gusto reserved solely for choruses. Get a group of people together at a table, serve them beer until they’re happy and put this song on; you’ll see what I mean.

This record in turn became the turning point of Springsteen’s career, the center around which he still turns. The Darkness at the Edge of Town and its wealth of material, carved down to a single disc and restored about a decade ago, was a mirror image of this record, bleak where Born was brimming with confused promise, a cynical answer to the yearning. The River, a double album, was a continuation. Those three comprise the core of the E Street sound, half a decade of the group drilling into the perfect rock of Born to Run and permanently cementing a sound that, if we’re honest, every single great heartland indie rock group since has been aping. This is the sound of the rustic glory of America, beyond the bullshit and genocide, beyond the evils of the politicians and the racism and imperial urges and capitalist wickedness that stain its history.

Even the records afterward feel like a response to this one. Nebraska as a paring down, intended to be another repetition of these forms (repetitions we still see in its live arrangements) but wisely encouraged by the rest of the band to stay as spare country-folk, another style Springsteen would return to again. This stylistic spoke would gift us with records like The Ghost of Tom Joad, The Seeger Sessions and Western Stars, among others. Born in the USA, a pair even just in title alone, naming the thing he was running from all those years ago, produces a slickness to answer the ornateness, which would produce another of his styles we would see pursued in Tunnel of Love, Human Touch and Letter to You. Springsteen’s career from The Rising onward can be read as him navigating the space between these styles, from the pop-driven approach of Magic to the loose Born to Run/Born in the USA trilogy closer Wrecking Ball to the spare and latter day Nick Cave-like High Hopes. It’s a discography of wonders, a treasure chest of gifts, all finding its source here.

***

The narrative of this record became a guiding beacon for me. Oh how many nights I spent in college and the years after, awake at 2 a.m. drunk on beer, empty bottles crowding the table like so many dead in the hazy artillery smoke clinging to the cooling earth after a battle, weeping and ranting with my friends Rob and Peter and Evan and Matt about our shared curse of masculinity. We were all AMAB and all to varying degrees struggling with gender, each finding our own solutions to that problem. We found a shared nexus in this record, the way Bruce cut deep past the bullshit and bravado of manhood to its fragile core. I feel pain and I don’t know what to do with it. I wasn’t taught as a boy how to process pain, grief and anger. I was told to be silent, strong, that specifically strength is a function of denial of emotions rather than their healthy processing. Ignoring even my own disjunct from maleness itself, this kind of tutelage fucks you up.

We seek women for many reasons, but the ugly and stupid heart of it is a sense of completion, that we might learn the thing that expels at last years and decades of concatenated scarred-over pain, before we go too crazy, before we hurt too many people, before it becomes something we can’t take back. This arc, it should be said, is literally what occurs in alchemy: the sun and moon, the yin and yang, the completion of the self. As any decent feminist would tell you, if you seek these things from a real flesh and blood woman, you are enacting an objectifying violence upon them; what you seek for is a kind of Irigarayan metaphorical “woman” within yourself, not so much a gender as a function. To find a way to slide a knife between the plates of the armor, wrench the chains apart so it falls clattering to the floor and our wounds can be exposed to open air, to be clean and sutured. We dream of masculine violence as a form of intimacy, a way to externalize pain and literalize it; we weep like children when sick in melodrama because its one of the few times we are allowed, even just by our own psyches, to be weak and ask for the help we want almost all of the time. It is a form of submission that must be learned: submission to the reality of your own heart, to look past the surface of our desires to the things that cause them, the roots of our yearning, the roots of pain and hope.

I was a drunkard in my early twenties, rife with madness, struggling through psychotic episodes and suicidality. I would drain a bottle alone at the kitchen table where my father likewise drank himself to death, a cruel repetition I enacted deliberately in the theatricality of my pain. I would listen to Born to Run and dream of being free. I would cry with my face pressed against the bony crook of my too-thin elbow, weak from starving myself in an eating disorder I wouldn’t truly tame until I’d faced my gender demons, listening to Bruce sing about that yearning, the desire to be free. I walked the streets of Atlantic City with my childhood friend Mark, both of us fresh and seething from the loss of our fathers, the cold ocean fog rolling in on empty beaches, “Jungleland” in my ears. I would sing “Thunder Road” to Dana, the first person I ever really loved, wincing at the line about not being a beauty (she struggled with self-image but always was a beauty to me); after I squandered her love and our tentative engagement, I’d sing it to myself in the shower to remember how I’d fucked up, how my overly-masculine pain from a gendered heart riven with confusion had driven her away. This too was a mirror of me singing the same song in the shower to myself when I was 12, 13, desiring to know a love that might fit this perfect image. I would sing “Thunder Road” into the ear of my friend Duna when we were both drunk and confused, making out with each other under starlight despite her having a boyfriend (now her husband) and me being nowhere near capable of being there for anybody. I sing it now to my wife and, still, to myself.

My friend Rax King wrote a beautiful essay about her own navigation of the myth-image of Bruce Springsteen, the way he reminds people of our age of our fathers. Ours were both born around the same time, kids of the ’50s and ’60s who came to adulthood just as Bruce did, wearing the same leather and slicked hair already 20 years out of date but reminded themselves of the rebellious queer masculinity of James Dean. My father was, as far as I could tell, always a man. I have seen the uncomfortable sight of my mother literally swooning looking at a picture of him, shirtless and muscled, tanned and slick with sweat, face pressed to a microphone and a Telecaster in his lap, the same kind of guitar Bruce has slung to his back on the cover of Born to Run and the same guitar he learned to make talk in “Thunder Road.” I can listen to either side opener on their own, two perfect beacons.

“Thunder Road” may be my favorite Bruce song, but “Born to Run” is his best. It’s everything he ever was, all the complex art rock arrangements and compositions melded into a pure post-Beach Boys Americana, a prog epic in 3 minutes, a perfect scroll of a song like Walt Whitman unfurling a new poem to answer Blake’s odes to England. To listen to those other gems, I have to listen to the entire record. “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out” on its lonesome is perhaps slight; in the grander narrative of those braided stories, the questing heart searching for a woman that might be home, a home that might paradoxically be freedom, freedom that might be love itself, it is a rich and necessary chapter. “Night” is a chilly gothic beauty, a song calling midwest emo into being from decades in the past in spirit if not in form, while in context it is the abyss of the soul. “Backstreets” doesn’t make sense unless it bursts into “Born to Run” right after, like they are movements of a greater piece rather than distinct songs. And “Jungleland,” that immortal epic, is not a song but a concluding movement. It’s not that it isn’t good enough to stand on its own. It deserves the weight of that full emotional journey behind it, so that when Bruce finally hits that wordless cry at the end, you feel that same cry building in your own chest, an explosion of grief and desire, love and hope. Yearning.

***

The most striking thing about Born to Run is how it has resonated to me through so many moments. It doesn’t have a ring of nostalgia to it except in the Proustian sense, the way it beckons me to unfurl myself and remap the universe of self again and again after each checkpointing revelation (every life is scattered with haphazard revelation). Whenever I return to it, it does not feel like Bruce Springsteen and company are weaving a poetic novel to some former me: there is a perpetual freshness, a missive fired by arrow through the corridors of time to land at my feet precisely now. It has answered my cries again and again, been a polestar in the years of my confusions. I am often imperfect; I struggle to know how to be, to even know who I am. Springsteen’s catalog always returns, but it is this record in particular that seems to call to me again and again through the years, preserved as though the strongest of medicines. I hear it now in my mid-thirties a deeply different person, resolving to the best of my abilities my constant struggles with gender and selfhood, the question of who I want to become having shifted into whether I am happy with the person I have become, and it sounds as perpetually fresh in its answers as when I stole it from my father at the age of six. By that point my father himself was in his mid-forties, finding himself faced with the same questions, wanting this record precisely because it held some answer for him at that stage of his life the same way it did when it first came out 20 years prior . My mother still fondly recalls it as conjuring the image of the type of man she could finally love. It is eternal.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.