David Bowie : Station to Station

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

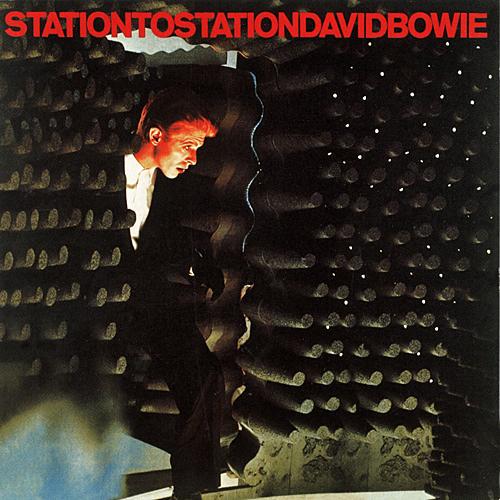

Ok, let’s see, he had already been a hippie folkster, a cross-dressing crooner, a Nietzschean philosopher, the personification of superstardom, an American glamster, an Orwellian prophet, and a blue-eyed (and brown-eyed) soul singer, all of that with each successive year and album that came with it. So, is it easy to call Station to Station a bridge between albums as the title now suggests? Yes, but mostly in the way that every album the man created was a bridge. David Bowie never stopped ch-ch-changing, switching personas as often as he switched his highly stylish outfits. The difference between the soul soaked and guest laden (John Lennon and Luther Vandross, R.I.P.) Young Americans and the Eno-driven Berlin trilogy which started with Low is vast. So Bowie called upon the Thin White Duke to close the gap. The mask of the Duke was essentially his retreat from the world. He had been in a dispute with MainMan Management and was having equal troubles with his wife, Angela. The character he played in his first film role, in The Man Who Fell to Earth, became his facade for months on end. He even went as far as to choose a still image from the film for the album cover. Emotionally Bowie was at an all time low (pun intended), but thankfully not artistically.

Station to Station was recorded while Bowie was in the grip of cocaine. While this is not shocking for anyone who followed the music industry in the ’70s and ’80s, what is shocking is how good of an album was produced by Bowie in that state. In today’s album reviews, it becomes difficult to speak to every song on a particular CD. You try to highlight the good ones and gloss over the rest. When an album only has six songs, things get a little easier, especially when all six are out-and-out gems. The 10-minute title track is the one most obviously written under the influence, at least on the surface, as it changes on handfuls of dimes. It begins with over one minute of train sounds, then leads into a plodding meditative prog rock song with wailing guitars and shaking rattles. He announces the return of the Thin White Duke, another one of Bowie’s many personae, within the first line, then after the song makes one of its turns into a bouncy chorus, Bowie admits the drug use, “It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine / I’m thinking that it must be love.” Bowie’s interest in the Kabbalah and other aspects of religion could have led to the use of the “European canon” line (often misheard as cannon) and the possible reference to the “stations” of the cross. No one could say Bowie wasn’t dramatic, but making himself a Christ figure? He did go on to play Pontius Pilate for Martin Scorsese.

“Golden Years,” an early working title for the album, is an obvious progression from Young Americans and a touching love note to his wife, as he longed for their innocent early days. It was the only hit from the album, in large part probably due to its likeness to its predecessor, its accessibility, and the sheer fact that it is the shortest track on the album. It would later, to both the delight and disgust of many, become a dance number in the film A Knight’s Tale. “Word on a Wing,” on the other hand, is more of Bowie reflecting on religion. This is a far cry from his dark thoughts of “Quicksand” where the afterlife and faith are foreign concepts to Bowie. In this, the veneer starts to crack, saying “Just because I don’t believe don’t mean I don’t think as well.” Bowie refers to the time as “an age of grand illusion,” referring to the anti-war (WWI) film by Jean Renoir, maybe this time reflecting post Vietnam confusion. “TVC15” was a landmark track in a number of ways, the first being that it was the debut of the “cut up” or magnetic poetry technique of songwriting that he cribbed from William S. Burroughs. He would write down thematic words, mix them up, and thus they became song lyrics. It is also an experimental song that would lead into his brilliant work with Brian Eno in Berlin, a style which would be echoed later through the years by many, even up to Radiohead’s Kid A.

“Stay” is a funk-driven song featuring the great Carlos Alomar on guitars and some of the best funk drumming outside of a James Brown record. The message is simple, it’s his plea to his lover to stay the night. Haven’t we all been there? Bowie’s warbling chorus is old style crooning mixed with a new style soul and as sparse as his singing in the song is, what is there is magical. How “Stay” didn’t become an international smash, I don’t know. The album closes with the down tempo “Wild is the Wind.” Bowie’s reputation as a crooner is given more fuel as he covers an old Johnny Mathis song that was the theme song for a film of the same name starring Anthony Quinn. Bowie is at his most earnest with this song that is not his own. Singing lyrics such as “let the wind blow through your heart,” though cheesy, sound achingly fresh with Bowie’s delivery.

Bowie, after the release of Station to Station would make his famous move to Berlin and begin a trilogy of albums that would gain critical acclaim, but in the meantime, he had become not only the Thin White Duke, addicted to cocaine, but also a movie star. Berlin would be the place he would finally kick the drug and gain a new perspective on art. As every door closes, another opens, and so, as the door to American soul and funk closed, the door to abstract European expressionism opened. Time to ch-ch-change again.

Similar Albums/Albums Influenced:

David Bowie – Young Americans

David Bowie – Young Americans

Kraftwerk – Autobahn

Kraftwerk – Autobahn

Brian Eno – Here Come the Warm Jets

Brian Eno – Here Come the Warm Jets