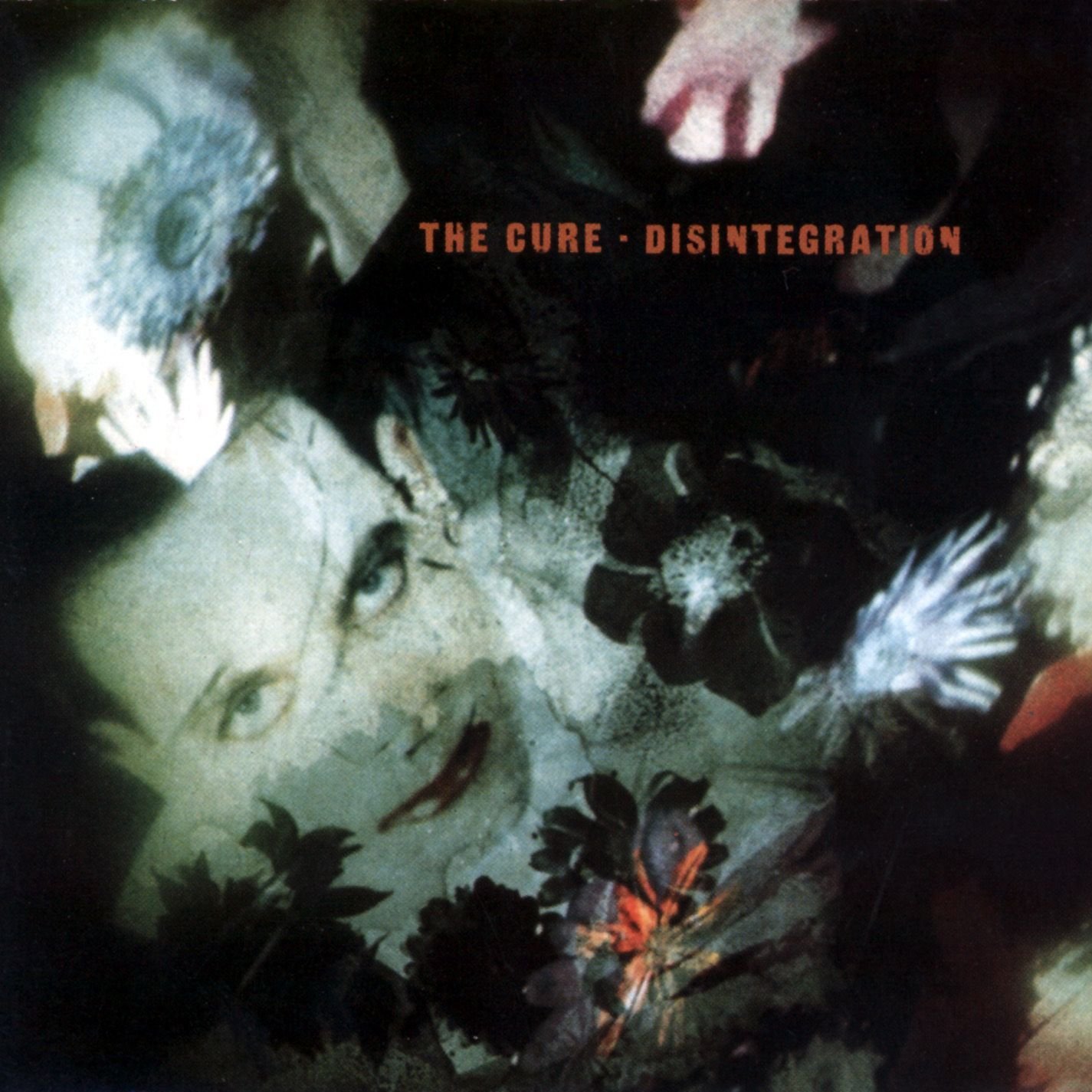

Disintegration: The Cure’s expansive masterpiece

At various points in my life I’ve concluded that The Cure’s Pornography and The Head on the Door were each my favorite of the band’s albums. The two albums represent the band’s most polarized extremes. On Pornography, they reached a harrowing goth-rock critical mass, creating one of the most dismal and harrowing collections of songs ever committed to tape. On The Head on the Door, the band revealed its pop-friendly side, delivering enduring pop singles like “Close to Me” and “In-Between Days,” which remain radio staples decades after their initial release. And each one, no matter how bright or how bleak, contains some of the best songs Robert Smith has ever written.

Depending on which day you ask me, I might still be likely to tell you that either of these classics is my favorite of the band’s 13 albums. There’s a pretty strong argument to be made for most of them, really: Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me is the first of the band’s albums that I personally owned, and one whose nostalgic connection is hard to shake. Three Imaginary Boys is the most fun, a spiky punk record that balances the badass with the truly silly. Meanwhile, Faith and Seventeen Seconds are nearly perfect post-punk albums, the former being a dark and ethereal standout, while the latter contains my favorite of the band’s songs, “A Forest.”

Disintegration, however, is the band’s masterpiece. It’s hard not to marvel at how long the album has been in the world, its gothic grandeur timeless and ageless, as fresh as if it were released yesterday while bearing the sound of an immortal relic. What’s even more striking is the revelation that this was the band’s most successful album. This introverted, dark and expansive album, one whose songs mostly roam past the five-minute mark, some just shy of ten, somehow went double platinum, selling more than two million copies in the U.S.

There’s an entirely logical explanation to the eventual explosion of the band’s sales figures. Their prior album, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, went platinum statewide, and launched a series of ubiquitous singles, including “Just Like Heaven.” It was probably inevitable, following this wildly successful run, that whatever came next would move a record-breaking number of units. Yet, for such a “difficult” record— one which Elektra Records dubbed “willfully obscure,” as revealed in Jeff Apter’s Never Enough—there were four immense singles on the album, “Pictures of You,” “Fascination Street,” “Lullaby” and “Lovesong,” whose presence has become almost as ubiquitous as “Just Like Heaven.” The sales figures that followed, in addition to the near-universal adoration of the album, ultimately proved the suits at Elektra wrong.

For years, the album seemed almost too big, both in scope and in reception, for me to be able to be close to it. I always loved the album, but it took me a while to feel the personal connection to the album that I did with The Head on the Door or the aesthetic fascination with Pornography. Yet, knowing that the album was written and recorded in the year leading up to Robert Smith’s 30th birthday, upon approaching 29, I felt more connected to Disintegration than ever.

To clarify, my headspace had grown nowhere near as troubled as Robert Smith was at that age. For Smith, turning 30 was just as frightening a prospect as being eaten by the spider man for dinner. And while aging isn’t a central theme of the songs on Disintegration, Smith’s bleak mood shows throughout the album’s 71 minutes. Nightmares, loneliness, depression and death loom large over the album, as does Smith’s LSD use, to a certain degree.

Still, for an album with so much darkness on the surface, it’s by no means defeating. Rather, it’s the kind of album you listen to when you truly want to feel alive. One of its greatest aspects is just how incredible it sounds. It’s an enormous record in its sonic scope, something that’s flagrantly displayed within its first track, “Plainsong.” Its synthesizers are huge and commanding, more like the sacred tones of a pipe organ than any kind of rock instrument. In fact, it’s almost a misleading tease in the context of what, ultimately, is very much a guitar album. Smith and Porl Thompson’s effects-treated guitars define the sound of the album, shimmering and sparkling amidst a swirling and ethereal atmosphere. They soar over the melancholy dirge of “Homesick.” They add a vibrant crunch to the muscular “Fascination Street.” They jab with jagged accuracy in the ominous march of “Prayers for Rain.” And they provide a twinkling counterpoint to Simon Gallup’s beefed-up bassline on the title track.

Only adding to the album’s remarkable sound is the fact that, amid a kind of surreal darkness, there are moments of true joy. The pinnacle of Smith’s outpouring of emotion is “Love Song,” which was actually written for his wife, Mary Poole. Not only the rare song that shows a genuine display of affection, but a rare song for Smith, himself, in that it’s unencumbered by cryptic phrases or bizarre imagery. It’s simply a love song. However, Tim Pope’s video for the song featured a series of phallic stalactites that may have interfered with its sincerity just a bit. Still, it takes a certain level of fearlessness to be able to say something so personal without trying to wrap it in metaphors.

Disintegration is an honest and mature album, which is, perhaps, ironic in that it’s the most renowned and recognized album from a band so frequently associated with teenage angst. I understand how an awkward and bummed-out teenager would gravitate to its gloominess. But as we mature, the relationship between the music and its listener takes on a different meaning. Where once an album could be the company that one’s misery could love, later on it might become a more profound statement of humanity—more universal, more adult.

Looking back, it’s often puzzling to make heads or tails of Smith’s lyrical narratives—the blood of Christ, howling women, cockatoos, etc. It’s more like a psychedelic zoo than a life experience. But then again, that’s what I find so appealing in the band’s early records. They paint a vividly surreal picture that few other bands were capable of. When they released Disintegration, however, they created an artistic experience that even their best records only hinted at. It’s a gorgeous album, and in spite of its length, I can’t help but be drawn in by every stunning layer. And most importantly, the cast of characters that once flooded their albums like nightmarish sideshow acts was transformed into something real (except the spider man, of course).

I’ll never lose my affection for The Head on The Door or Pornography—those albums still give me chills to this day. But as I listen to Disintegration many years later, I feel, more confidently than ever, that this is not just the band’s best album, but one of the most amazing things I will ever hear.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.