The Cure’s ‘Seventeen Seconds’ is a cold, eerie post-punk masterpiece

It’s cold outside. The ground’s wet, the sun’s been AWOL for days, and the sky is a muted, murky gray. Not that it really matters; the whole planet has shut down and been directed to stay indoors as a result of a viral pandemic. It’s scary, sure, but more than that it feels eerie—as if life on earth just kind of stopped overnight, shells of commercial buildings left vacant and the occasional sighting of a neighbor scrambling to stay six feet away. It’s tempting to say it feels apocalyptic, but it’s more post-apocalyptic. We’re all still in hiding, waiting for the signal that it’s OK to breathe the outside air again.

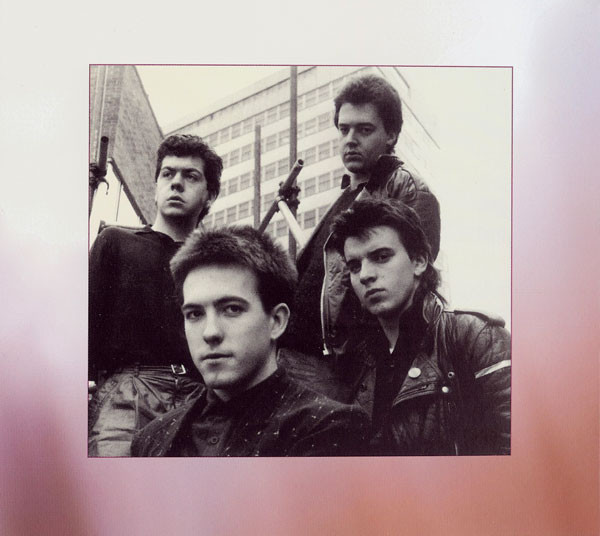

Which is probably why one of my first instincts while on self-quarantine lockdown was to reach for The Cure‘s Seventeen Seconds. Recorded and released before Robert Smith’s teased-and-sprayed mop became an icon unto itself, and before The Cure became the Official House Band of Goth, Seventeen Seconds opened a hatch into a dark and dour Cold War bunker. It’s not a harsh album—the band barely uses any distortion outside of a few key moments—but it’s a chilling one. You practically feel a shiver while gazing at the blurry forest image on its front cover, and the music doesn’t offer much warmth beyond that.

If Seventeen Seconds—which is now 40—wasn’t the beginning of The Cure as goth icons, it was at the very least their journey through the frosty passageway that led there. It’s not a dramatic album, certainly not compared to the harrowing experience of Pornography two years later, but rather a darkly minimalist one. The textures are sleek, the rhythms locked in, and where its predecessor, Three Imaginary Boys, presented the chaotic sound of three British teenagers bashing away and making no effort to take themselves too seriously—a pisstake cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “Foxy Lady” and a song called “So What,” with ad-libbed lyrics about a cake-decorating set, will do that—Seventeen Seconds is a maturation, a harnessing of control. Which goes for the presentation of the album itself; where their record label had chosen the track order for Three Imaginary Boys, Smith swore never to leave anything regarding his band up to anyone else from that moment forward.

Not everyone warmed to the band’s new direction immediately—as is often the case with music so cold and distant. The Cure were accused of having “no image, no style” by NME at this stage, which seems an ironic insult given the course of things. Image or not, Seventeen Seconds does have style. It’s streamlined and bound by hypnotic rhythm, a pulse driven by a kind of disoriented melancholy. Its closest contemporary at the time was probably Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, but the records that the band was inspired by at the time—David Bowie’s Low, Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks—aren’t ones that sound much like it. What they share is a similarly dark mood, a drive to transcend the expected, and a total absence of the cliché.

“There are loads of bands imitating the kinds of music they like,” drummer Lol Tolhurst said in an interview with WBUR. “We just said, ‘What don’t we like?’ Long lead guitar solos and very flamboyant drum fills. We’re not going to incorporate them so there’s no point in learning how to do them.”

It helps that, with Seventeen Seconds, The Cure was a different band than the one heard on Three Imaginary Boys. Bassist Michael Dempsey didn’t like the material that Smith had written for their second album, and left the band, joining The Associates. Bassist Simon Gallup took his place (and he’s still in the band—Smith says that “it wouldn’t be The Cure” if Gallup left), while keyboardist Matthieu Hartley briefly rounded out the group as a fourth member, touring behind the album only to leave before recording their third. But the trio of Gallup, Smith and drummer Lol Tolhurst formed the backbone of a series of albums that defined The Cure as standard bearers of British post-punk and gothic rock. This wasn’t where The Cure began, but rather when they fully arrived.

The focal point of the album in 1980 and what remains so today is the album’s knockout single “A Forest,” as perfect a song as the band ever recorded. It’s driving yet unsettling, gloomy yet hard-edged, a perfectly realized ideal of post-punk if there ever was one. As gothic rock, however, it’s somewhat understated by The Cure’s standards—held up against a moment of grandeur like Disintegration‘s “Plainsong,” it feels positively understated. “A Forest” has a dynamic climax, an instrumental chorus that conveys its mood perhaps better than lyrics ever could, though the lyrics that are here carry their share of ominous mystique: “Come closer and see/See into the trees.” Smith says that the song is, simply, just about a forest, which is a little like saying a T. Rex song is about a car. It’s technically true, but, you know…come closer and see.

Outside of “A Forest” and the album’s other notable single, “Play for Today,” Seventeen Seconds is more abstract, more distant. It’s spacious (“In Your House”), it’s jangly (“M”), sometimes heavy and creepy (“At Night”), and sometimes much weirder and less song-based. It’s here where the Low influence is more apparent; “A Reflection,” “Three” and “The Final Sound” are each instrumental mood-setters, doors opening into ever chillier corridors and more perilous alleyways. They don’t take up a lot of space on the record, in part because they work best when used sparingly, and in part because they ran out the clock. The tape ran out while the band was recording “The Final Sound,” and they weren’t able to record it again, which left the final version at all of 53 seconds.

Like all of the best Cure albums, Seventeen Seconds is a collection of great songs. But more than that it delivers a self-contained aesthetic experience, one of ethereal darkness and a quiet, unseen menace. Viewed in hindsight, Seventeen Seconds is often viewed as part of a trio of albums—with 1981’s Faith and 1982’s Pornography—that encapsulate The Cure’s peak post-punk era. There’s an apocalyptic sensibility to all three of them, but the narrative almost seems to play out backwards, with the intense and heavy Pornography representing the carnage, violence and mania; the somber and muted Faith representing the grief and mourning; and Seventeen Seconds the eerie calm after the weeping has ended. It’s a beautiful ruin.

It’s fitting that some of the band’s best albums sounded like the end of the world. Each one was written as if they were to be The Cure’s last.

“We honestly felt that we were creating something no one else had done,” Robert Smith told Rolling Stone two decades after its release. “From this point on, I thought that every album was going to be the last Cure album, so I always tried to make it something that would be kind of a milestone.”

Seventeen Seconds wasn’t the last Cure album, and 40 years later they’re promising three new records in one year. It’s hard to know how reliable an estimate that is right now, given the uncertainty of the industry and the unlikeliness of the band being able to book any kind of tour for most likely a year. But that’s OK. They’ve already made a perfect soundtrack for the strange, desolate and claustrophobic landscape we’re in.

***

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.

Pornography is my manic album and Faith my depressed album, in those brief moments of sanity, 17 Seconds is my album.